Xavier Dolan’s Top10

Québécois filmmaker Xavier Dolan’s debut feature, I Killed My Mother, won three prizes in the Directors’ Fortnight section of the 2009 Cannes Film Festival, and his follow-up, Heartbeats, competed for the festival’s Un certain regard. An avowed Criterion addict, Dolan tells us that during his last trip to Cannes, “my luggage was filled with Criterion titles.”

Photo by Shayne Laverdière

-

1

Jean-Luc Godard

Pierrot le fou

The ultimate freedom. Freedom of words, freedom of images, freedom of colors, and freedom of love. This is Godard at the acme of his art, the apex of his craft. A cinema that never denies itself anything.

-

2

Ingmar Bergman

Cries and Whispers

Overwhelmingly impressive— almost intimidating—acting. Mind-blowing technique. Sensitive and thorough portrayal of tangible pain, malady, sorrow, and loneliness. Oh, and fade to red.

-

3

René Clément

Forbidden Games

In my top three love stories. Narciso Yepes’s legendary score gives this juvenile romance its fame and contributes to its magic, but the movie is an entity of perfection. The artistic direction is meticulous and inspired; there’s a vanguard oneiric look to the film. Brigitte Fossey delivers an endearing and incredibly mature performance, and looks the epitome of femininity despite her—gulp—six years of age. Great opening sequence depicting the 1940s French exodus from Nazi occupation. Genuine and sensible study of youthful mores; creative representation of the children’s universe. Stunning grace and poetry. Heartbreaking departure scene. I love that film. It makes me want to be a pretentious critic.

-

4

François Truffaut

The 400 Blows

The first time I fell in love. And felt loved in return. Basically, my childhood (with nuances, of course)—I’m sure I am not the only one who was wondering where in my house they had hidden the cameras. Léaud at the top of his game; he did create, with time, his own acting rules, his own school in his mind, and he opened the doors to many other actors and actresses. One never really says, “Léaud is so bad in this or that film.” No. It’s Léaud, that’s it. Plus, you can never think of anyone to replace him. Never. This film clearly does justice to its title. It blows us away. I don’t feel very original when I say that this is the movie that made me want to direct. And that reminds me all the time how much there is still to learn.

-

5

Abbas Kiarostami

Taste of Cherry

A powerful journey through despair and silence. A magnificent reflection on death and the meaning of life, as well as the ways life sometimes unveils its beauty—by, say, the taste of cherries that have fallen from a tree, a tree shaken by a man who was planning to hang himself on one of its branches but who remembered, when savoring these wild berries, that life is worth living. Long single takes, car scenes (for which Kiarostami is famous, and rightfully so). A gem. Must see. Now, please.

-

6

Mikhail Kalatozov

The Cranes Are Flying

A vanguard film (again). 1957. A great love story. But mostly a work of overimpressive technical virtuosity. Breathtaking crane shots, hair-raising forest sequences (with a memorable rotating low-angle shot of trees dissolving into one another), an amazing and very swift traveling shot (captured from a tram in movement) in which the lead actress dives into a crowd, looking for the man she loves. We follow her, and once she is stopped by a fence, we tilt up fluidly, and end the scene with a great ensemble shot. Superb art direction, superb lighting, with curtains flying in the wind, hiding the face of the actress, partially lit with lightning flashes. A true work of art. Tatyana Samojlova, who won an award at Cannes for this role, is brilliant and touching, and delivers a rather minimalist performance for its time.

-

7

Louis Malle

Au revoir les enfants

Malle is one of my favorite directors. He flirts with genres, tries all sorts of things, travels all around the world, refuses to let go of documentary, his first love (or first milieu)—although his fiction movies are acclaimed. This film, close to his skin and past, is a strong coming-of-age work, set in France under Vichy. Often, in the middle of the day, I think of scenes from Au revoir les enfants, moments of grace like the restaurant sequence, with the mother. French officers burst into the place and ask for citizens’ papers. They find an old Jewish man dining quietly at his table and start to reprimand him, asking him if he knows how to read; the place is, of course, forbidden to “youtres,” as the young French officer says insolently. Suddenly, every patron at the restaurant starts yelling at the officers, insulting them (“Collabo!”), forcing them to leave. And then, among the clientele, German officers stand up and order them to exit the place. Strong turning point. That is exactly Malle, in there, striking again. Contrast, antagonism, emotions, brute emotions. The rest is craft and mastery. But emotions. That is what he aims for. That is what we get.

-

8

Jean Cocteau

Beauty and the Beast

Uh . . . 1946. How is this movie possible? All the steam, the fades, the technical effects that would be passé today were then revolutionary. And that is exactly what Cocteau was. Revolutionary. All the little smart creations: chandeliers held by arms through walls, the mirror’s powers, the pearls magnetically drawn to the hand, their flying at the end. Nineteen forty-six! Loving this film is probably a radical statement of sexual identity. I know that. Whatever. Nineteen forty-six. Yes, that is correct.

-

9

Gus Van Sant

Mala Noche

Van Sant is my hero. This movie is a concentration of all the things I love from him: brilliant camera games, muted and unsatisfied love(s), beautiful car scenes. The voice-over is stirring and true, and never useless or superfluous. It is authentic, intimate, universal, and ageless.

-

10

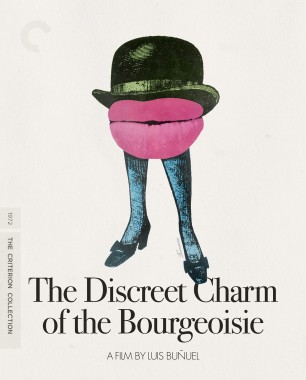

Luis Buñuel

The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie

A delicious incursion into the bourgeoisie. Flavorful performances, surprising turning points, incredible finale, and, as always in Buñuel’s cinema, a scrupulous care for details. And each of these contributes to the magic of the film, building a harmonious whole. A particularly droll, strange, and intellectual work about wealthy people.