Ruben Östlund’s Top10

Ruben Östlund is the director of the acclaimed films Force Majeure and The Square, the latter of which won the Palme d’Or at the 2017 Cannes Film Festival.

-

1

Volker Schlöndorff

The Tin Drum

Both the film and the book had a big impact on me when I was a kid. I don’t remember how old I was when I first watched it, but the film was told from the perspective of a young boy who is experiencing the adult world and discovering that it’s horrifying. I remember specific scenes that have an impact on me more than the film does in general. There’s one in which the characters are fishing for eels in the sea—that scene has affected me in such a way that I have never eaten eel since. Not long ago I showed the film to my brother’s young son, and I was looking at his face and his experience watching it, and I realized that it could have the same impact on this generation growing up now—he was horrified! But at the same time, it’s fascinating.

-

2

Paolo Sorrentino

The Great Beauty

This film has a certain kind of dynamic and rhythm that’s unique to Paolo Sorrentino as a director. It’s constantly a sensation, and there are some images in the film that I will never forget—for example, the facial expression of a nun when she’s climbing up the stairs. It’s really, really beautiful. It’s image porn when it comes to Rome, a city that I don’t like to be in that much but that I like to look at in films.

-

3

Catherine Breillat

Fat Girl

I actually prefer the French title, À ma soeur! (To my sister!). I think that some people see Catherine Breillat as a theoretical director, but I think of her as a humanistic one, and you get that from the title. The sister in the film is trying to fit into this family, and the way that Breillat looks at her is so beautiful. The girl is yearning for physical contact in such an intense way.

-

4

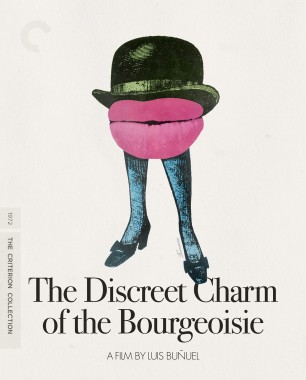

Luis Buñuel

The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie

This is the best film title in the world, and I wish so much that I had come up with it myself. It’s a completely absurd film. Buñuel dares to make a movie about this group of people who want to but never manage to eat dinner. There’s a moment when a hand comes up and tries to grab a piece of food off the table. He has no respect for the audience at all, and that of course makes him very interesting. I also like the way he dealt with his public persona. He was very free, and he was playing around in a way that gave him distance from the whole circus. When he was nominated for an Oscar for The Discreet Charm, a journalist asked him how he thought it was going to go, and Buñuel said he would win because his producer had bought the Oscar. And then he actually won and in his award speech he said that you can say whatever you want about Americans, but at least they stand by their word.

-

5

Jacques Tati

PlayTime

This film is the most ambitious failure. I love Tati as an actor, and I love the way the scenes are made; they’re so intelligent and funny, and the timing is fantastic in each and every moment. It has a Chaplin-like precision. But it’s also a black hole that sucks energy from the audience. I also really love his short films, like the one where he’s teaching actors how to walk into a wall properly. For me, Tati took acting to a level comparable to sports. His performances are very direct, and you can see his skill as an actor.

-

6

Rainer Werner Fassbinder

The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant

This film is so well-written and so beautiful. I’m so inspired by the way Fassbinder used the maid, a character who doesn’t speak but is always listening and always present in the room. She creates such an energy; it’s a very smart way of using a character. I tried to do that with some of my own scenes in The Square by adding a museum guard. I’m obsessed with details, but then I see someone like Fassbinder and think, oh, come on! Why did I put all this energy into that when it doesn’t matter anyway, because the film is about something entirely different? I can get very jealous because he’s so smart that he doesn’t even have to be obsessed with details.

-

7

Vittorio De Sica

Bicycle Thieves

For my mentor Roy Andersson, De Sica was someone who was looking at individuals within a social structure. His films were looking at societal problems in a very political way, with a very realistic style of shooting, but at the same time, they were very self-aware about their set-ups. I love the scene when the father and son go to a restaurant to spend the last of their money to eat something, and at another table is a different family, with a young boy who is looking at the son. I’ll never forget the way they look at each other and the look of the other boy, who is used to being in fancy restaurants eating pasta. It’s so touching and such a humanistic way of looking at things.

-

8

Stanley Kubrick

Barry Lyndon

It’s quite interesting how a film like this can work so well. The acting style is so uptight, but Kubrick creates such curiosity for the images and the structure and the narrative—I don’t know how he did it. I’ve rewatched it many times. There’s one scene that inspired the monkey imitation scene in The Square. A boy is taking his kid brother into the room where his mom is playing the cembalo. He’s wearing these wooden shoes, violating the strict etiquette of the room, and they start to fight. They actually used handheld cameras for that scene. When you think of Barry Lyndon, you don’t think of handheld cameras!

-

9

Lars von Trier

Antichrist

I think this is Lars von Trier’s strongest film visually, and I love the set-up; he’s so good with set-ups. A couple has lost their child, and the man is a psychoanalyst. He has decided to treat his wife himself, and his method is to put her in constant contact with the source of her neurosis. You can almost hear von Trier laugh when he’s telling the story. Quite often I feel that the set-ups that von Trier deals with are stronger than the films he’s making, but with Antichrist I think he goes the whole way. He’s just such a provocateur. With this film he’s getting to the core of what makes being a human being painful.

-

10

Michael Haneke

Code Unknown

I watched Code Unknown when I was in film school, and I left feeling like I had to pick up the trash in the cinema, like I had to take responsibility. What he was pointing out about individual responsibility toward other human beings really struck me hard. I must say I am grateful that Haneke exists in this time. He has such a European way of making films—it’s beautiful, but he shows no mercy.