Tears and Giggles

Two months ago, many of us were wondering whatever happened to Howard Hawks. Sight and Sound had just published the results of its Greatest Films of All Time poll of 1,639 critics, programmers, and scholars, and none of his films had made the top one hundred. This week, that list expanded to 250, and four of Hawks’s movies are in. Rio Bravo (1959) shares the #101 spot with Forough Farrokhzad’s The House Is Black (1963) and Agnès Varda’s Vagabond (1985), and just a bit further down the list we find Bringing Up Baby (1938), Only Angels Have Wings (1939), and His Girl Friday (1940).

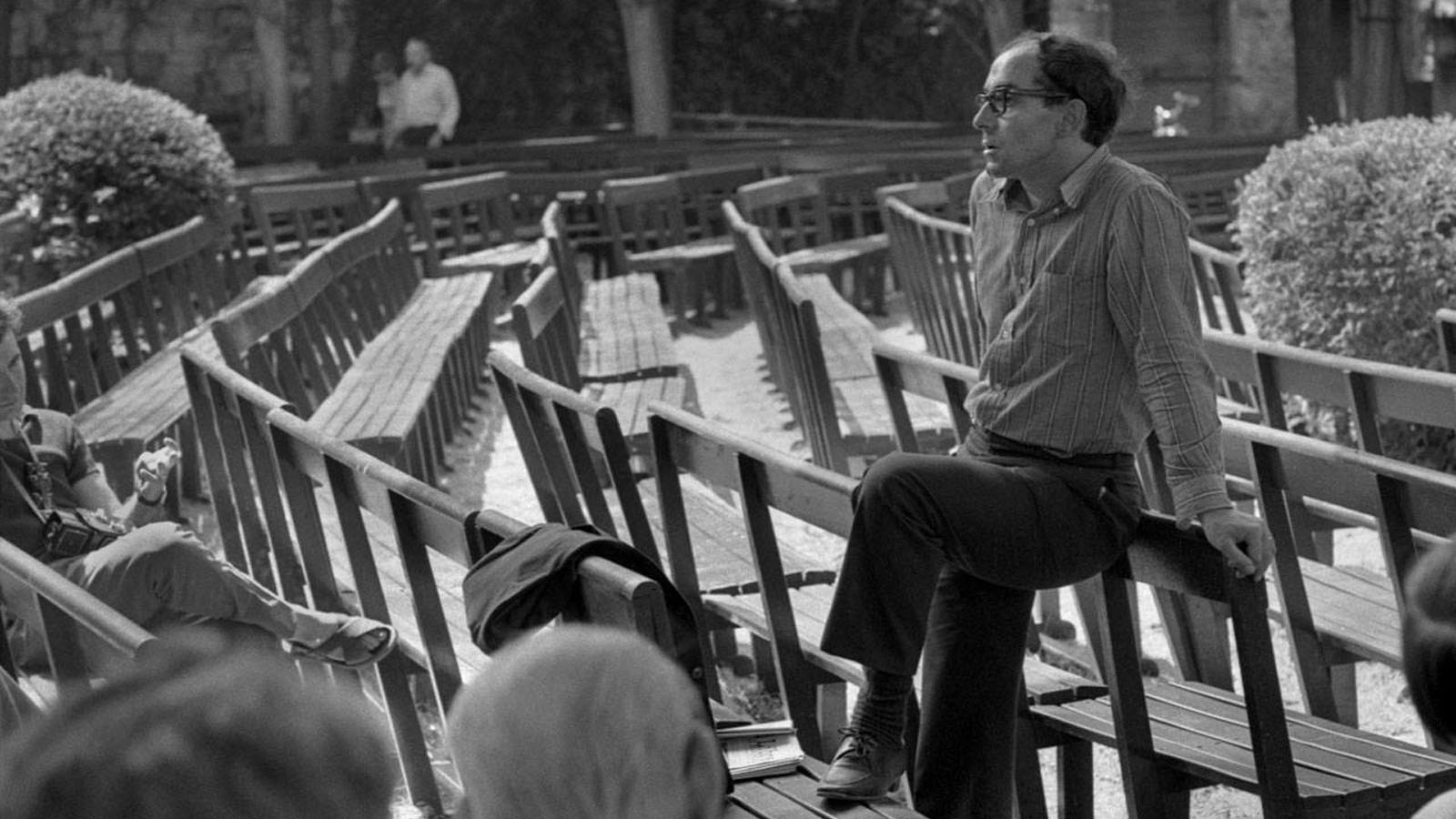

- Melancholia permeates much of the Notebook’s outstanding collection of seven brief pieces on Jean-Luc Godard. A scene from Keep Your Right Up (1987) once again has Richard Brody tearing up, Andréa Picard revisits a moment in Soft and Hard (1995) that “never ceases to seize my heart,” Miguel Marías writes about JLG/JLG (1994) as an “equivalent of some sort of epitaph,” and Lucía Salas asks, “how do we begin again?” But there are moments of celebration as well. Ephraim Asili connects the dots between the French New Wave and the Black Arts Movement, A. S. Hamrah recalls the teenage thrill of chasing after that first brush with Breathless (1960), and most thrilling of all, Rachel Kushner, drawing on notes from Tom Luddy, reconstructs the shooting of one scene in Une bonne à tout faire on the set of Francis Ford Coppola’s One from the Heart in 1981. Edited for an exhibition in 2005, Une bonne à tout faire is “one of Godard’s most beautiful films.”

- With On the Bowery: Lost and Found Films of Sara Driver running through next Wednesday at New York’s Roxy Cinema, Sierra Pettengill (Riotsville, U.S.A.) talks with Driver for Screen Slate about casting unemployed Russian soldiers as extras in the ghost walk scenes in When Pigs Fly (1993) and dealing with Neo-Nazis and negligent producers while shooting the film in Wismar, the northeastern German town where Murnau shot Nosferatu (1922). “I had the weirdest dream the other night where I was tickling an alligator,” says Driver. “Under its arms. And it was laughing, and it had a big smile.” SP: “I think that is a perfect metaphor for your films! Like going so close to the mouth of the beast and then . . .” SD: “. . . giving it a giggle.” Driver has written her next film, which Nicoletta Braschi, her close friend and lead actress, describes as “Alice in Wonderland at the end of her life.”

- Kira Muratova once looked back on shooting The Asthenic Syndrome in Odessa in 1989 and noted that she “had the great fortune of working in a period between the dominance of ideology and the dominance of the market, a period of suspension, a temporary paradise.” The quote comes from a marvelous piece for the Paris Review by poet, musician, and translator Timmy Straw, who writes that “the film is a realization of inbetweenness, an assembly of frictions and crossover states we feel through form: through Muratova’s use of juxtaposition; through her uncanny overpatterning of echoes and coincidences; through the shifts of register between documentary and opera. The film doesn’t proceed so much as weave itself in front of us, in a dazzling ivy pattern of zones and occurrences. You could call it late-Soviet baroque realism.”

- Joyce Chopra will be in Cambridge this evening when the Harvard Film Archive screens Joyce at 34 (1974), the landmark documentary she shot with Claudia Weill, and Smooth Talk (1985), Chopra’s debut feature starring a then-eighteen-year-old Laura Dern. “The event is being held in celebration of Chopra’s recently released memoir Lady Director, a blisteringly candid and compulsively readable tell-all from a trailblazer who isn’t afraid to name names,” writes Sean Burns for WBUR. Burns walks us through the stormy career all the way up through Molly: An American Girl on the Home Front (2006): “I can’t believe I cried at a movie based on the backstory of a plastic doll.” Chopra is also Thom Powers’s guest on the latest episode of Pure Nonfiction: Inside Documentary Film.

- One of the challenges CGI presents to filmmakers and scholars alike “involves recognizing the hegemonic studio aesthetic as just one of many possibilities,” write Luise Moerke and Jack Seibert in the introduction to the dossier they’ve guest-edited for Senses of Cinema. The new issue also offers articles on Federico Fellini’s Amarcord (1973) and puppetry in Leos Carax’s Annette (2021) and Krzysztof Kieślowski’s The Double Life of Véronique (1991) as well as interviews with Dominik Graf (Beloved Sisters), Christophe Honoré (Les chansons d’amour), Mark Jenkin (Enys Men), Ann Oren (Piaffe), Cyril Schäublin (Unrest), and the late Amy Halpern.