Time and the Times

When Vladimir Putin invaded and then annexed Crimea in 2014, filmmaker Oleg Sentsov (Gamer) helped deliver food and supplies to Ukrainian military personnel trapped on their Crimean bases. He was arrested and tried for “plotting terrorist acts,” prompting Pedro Almodóvar, Ken Loach, Béla Tarr, Wim Wenders, and other European directors to sign an open letter of protest. Though he had been slapped with a twenty-year sentence, Sentsov was released in 2019 as part of a prisoner swap between Russia and Ukraine.

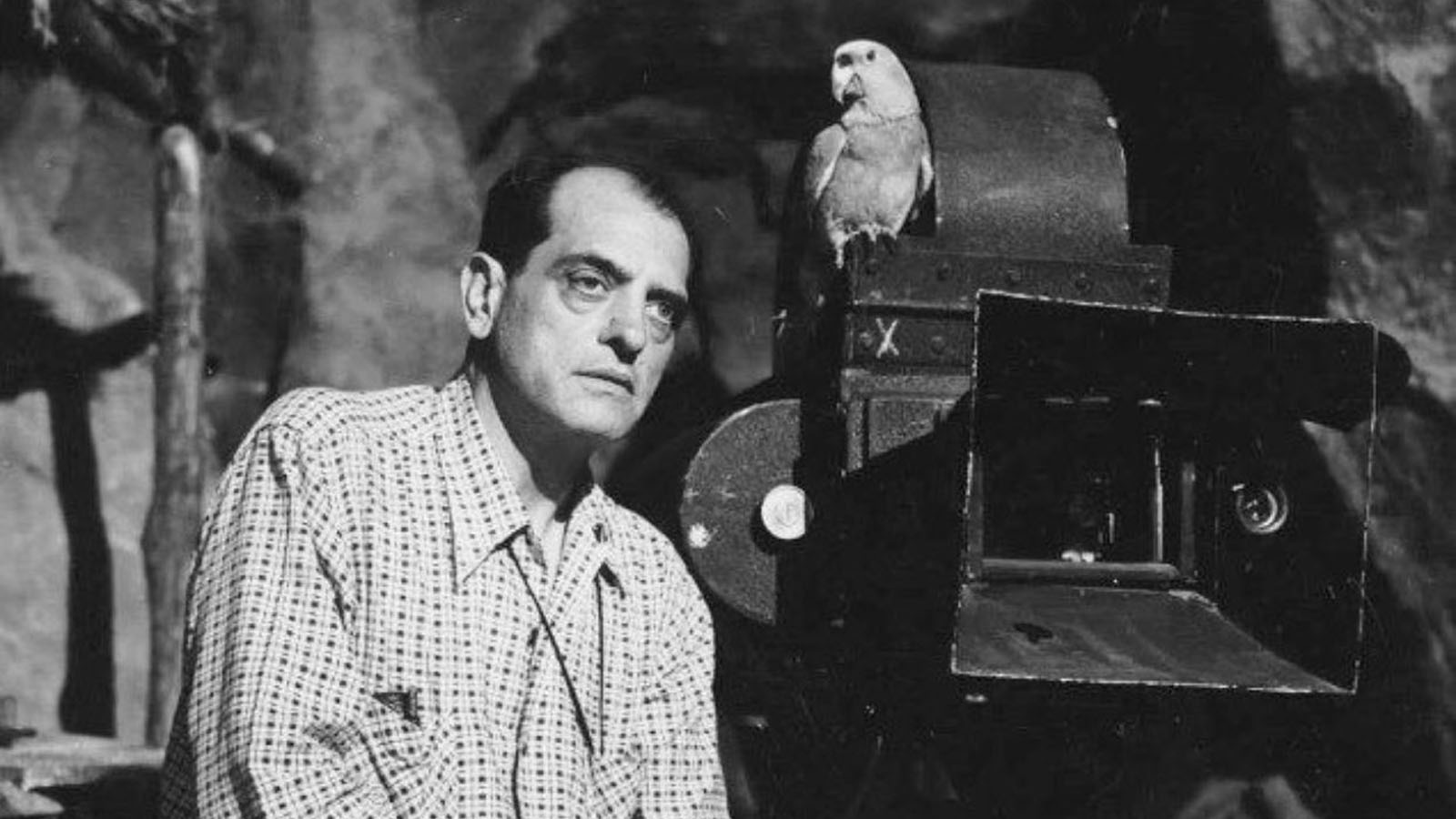

- Srikanth Srinivasan has translated a short monograph on Luis Buñuel that Luc Moullet wrote in 1957—when he was nineteen. Buñuel had made the Surrealist classics Un chien andalou (1929) and L’âge d’or (1930) and his great Mexican films Los olvidados (1950) and Él (1953), but he wasn’t yet the international giant behind such films as Viridiana (1961), The Exterminating Angel (1962), and Belle de jour (1967). “Located as far from pure and simple anarchism as from blissfully hypocritical conformism,” wrote Moullet, Buñuel “concurs, by way of surrealism, with the preoccupations of the greatest spiritualist filmmakers and novelists. Profound disagreements between great creators exist only at the level of superficial oppositions; the French critic Eric Rohmer rightly remarked: ‘Buñuel resembles Hitchcock like the South Pole resembles the North Pole.’”

- Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise (1995) gave us a prime slice of the Ethan Hawke we had come to know from such films as Dead Poets Society (1989) and Reality Bites (1994). “God, what a beautiful, insufferable son of a bitch he was!” exclaims Jesse Hassenger in his final Together Again column for the A.V. Club. Hawke and Linklater have collaborated on a good number of features, but Hassenger’s focus here is on how Hawke has seemingly matured in the gaps between the cuts in the twelve-year project Boyhood (2014) and in the nine years separating each of the films in the Before trilogy. “So,” wonders Hassenger, “did Hawke really become a better actor over those twenty-plus years, or did time just pass? Linklater’s talent lies in the way he moots that question.”

- The exhibition Jonas Mekas: The Camera Was Always Running, one of several marking this year’s centennial, is on view at the Jewish Museum in New York through June 5. “Every archivist is perhaps something of a hoarder, and vice versa,” writes Nick Pinkerton at 4Columns, “but quite a bit of what Mekas held on to was more valuable than yellowing stacks of the Daily News, by virtue of the fact that he’d had an exceptionally interesting life, from ‘displaced person’ in the mire and muddle of postwar Europe to prime mover and shaker in the midcentury New York art world.”

- At Illuminations, John Wyver points us to “The Weirdness of Zoetropes,” Stephen Herbert’s marvelously illustrated study of the animation devices that delighted viewers decades before Auguste and Louis Lumière introduced their cinématographe. “Characters eating others was quite a popular subject,” notes Herbert. “In a strip by H. G. Clarke of Covent Garden, London, Beauty is gulped down by the Beast, only to immediately and conveniently re-emerge from its ear before being swallowed again, ad infinitum.”

- A single shot in Carlos Reygadas’s debut feature, Japón (2002), has sent Greg Gerke to lines from Wallace Stevens, Louise Glück, and Theodore Roethke and brought back a memory of an October afternoon. “I found my history in Japón, in all its eddies and distortions, its freeze-frames and fast-forwarding,” writes Gerke in Caesura. “The encounter has estranged me from who I thought I was—my heart has leapt onto a different cloud. And now I’ve written down my account of it, how it tattered and sustained me for days, as all great art does.”