New Issues for a New Year

In the few weeks since the last Friday roundup, a mob stormed the Capitol at the president’s bidding, Democrats won control of the Senate, and a new, highly contagious variant of the coronavirus has been leaping from continent to continent. As the pandemic rages on, critics and film industry watchers paused over the holidays to take stock of the impact it’s been having on the making and viewing of movies. “We’ve sometimes used ‘the studios’ as a slightly anachronistic synonym for Hollywood,” writes A. O. Scott in an exchange with Manohla Dargis in the New York Times. “Are we entering the age of ‘the platforms’?”

- In the cover story for the new Cinema Scope, Michael Sicinski places the five-film anthology Small Axe in the context of both Steve McQueen’s early work and the BBC series Play for Today (1970–1984). “While Mangrove is the most ‘complete’ Small Axe film, in terms of the conventional grammar of prestige cinema,” writes Sicinski, “Lovers Rock is the most fully realized work of art.” Also in this issue, Phil Coldiron writes about La Nature, “at once a summary of the recurring formal and thematic concerns of [Armenian filmmaker Artavazd] Pelechian’s career and an expansion into new realms,” and Erika Balsom reflects on the experience of watching crowds in isolation: “Jean Epstein wrote that picturing the crowd is ‘where the cinema will one day find its own prosody.’ Without the desire or ability to create such representations, [Jean] Douchet frets, ‘The secret of the métier is lost.’ What would cinema be without the crowd? What would film criticism be without hyperbole?”

- The first issue of Screening the Past in well over a year opens with a dossier on Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool (1969). “To a significant degree,” writes Stephen Charbonneau in his introduction, “all of the contributions here position Medium Cool in relation to historically adjacent film practices: transnational and domestic; narrative, documentary, and art cinema.” The new issue also features Joe McElhaney on Elaine May; Murray Pomerance on subtle yet consequential gestures in Luca Guadagnino’s I Am Love (2009), Alfred Hitchcock’s Family Plot (1976), and David Lean’s Brief Encounter (1945); and published in full for the first time, Kinopraxis, a one-off issue from 1970 devoted entirely to Jean-Luc Godard.

- Film Comment has been on hiatus since last summer, and Imogen Sara Smith has been missing it. “Compared with the loss of lives, jobs, homes, and democratic ideals, its disappearance may seem minor,” she writes at Reverse Shot, “but for the cinephile community, already deprived of the chance to come together in movie theaters and at film festivals, its absence hurts.” We read film criticism “not just for the light that smart writers can throw on cinema, but for the way that cinema, like a projector’s beam, lights up the minds of smart writers.” And Film Comment’s “greatest strength has been hewing to former editor Gavin Smith’s un-improvable editorial motto: ‘It was all about the writers.’”

- For the Los Angeles Times, Carlos Aguilar has spoken with director Alejandro González Iñárritu, cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto, screenwriter Guillermo Arriaga, composer Gustavo Santaolalla, and actors Gael García Bernal, Adriana Barraza, Vanessa Bauche, and Goya Toledo to put together an epic oral history of the making of Amores perros (2000). “It’s a movie that looks at the characters with a multidimensional gaze,” says Iñárritu. “Each of them belongs to a distinct class stratum in Mexico. This triptych of stories was a mosaic that included, not everything, but a great part of a society as complex as ours. That has remained faithful to what we still are.”

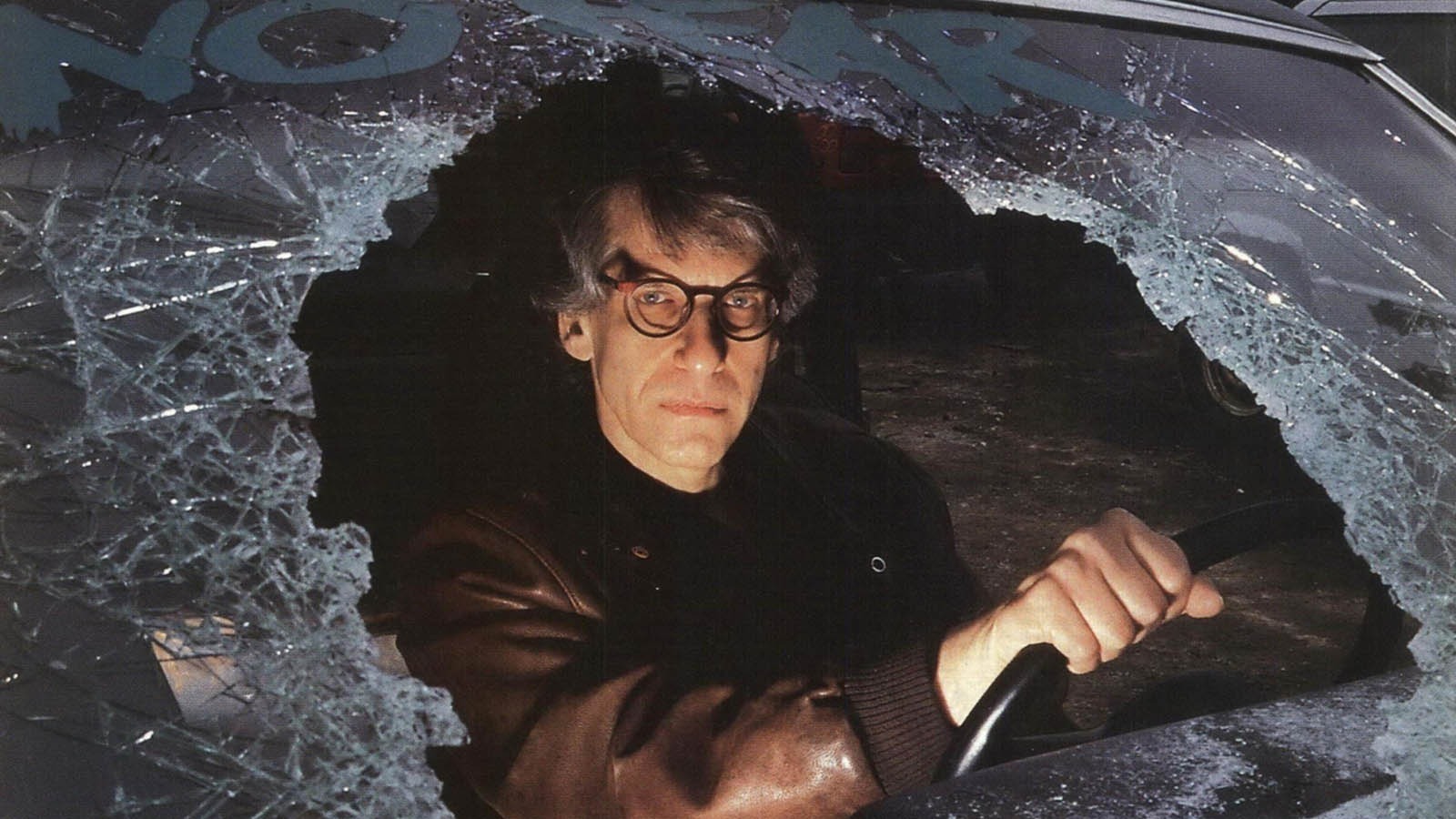

- Filmmaker has pulled up a 1997 cover story from its archives, Scott Macaulay’s conversation with David Cronenberg about Crash (1996), his adaptation of J. G. Ballard’s 1973 novel. “There’s a very old primordial trigger,” says Cronenberg. “Members of your species are dying, so you should become sexy so you can mate and procreate. Sex and death. Thanatos and Eros. Understood for thousands of years.” Writing for Filmmaker last October, Joanne McNeil argued that a “lack of subtlety” in Ballard’s novel “animates its many adaptations, and each articulates the central bleak vision: Eventually, the new will be old, all systems can and will break down, civilization has a limited moment of survival and isn’t infinite, that which we build for security or convenience might be the death of us.”