Film Comment and More

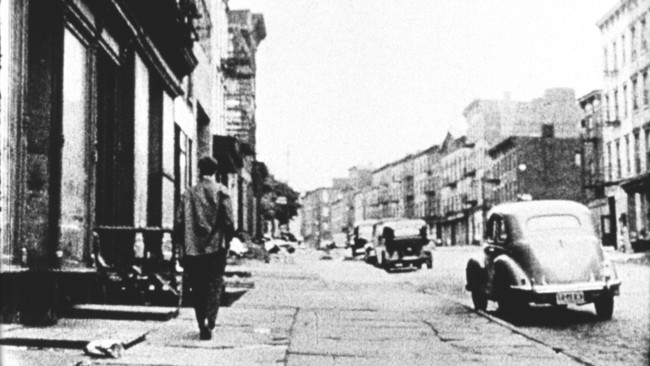

“A complex and layered work, [Jonas Mekas’s] Lost Lost Lost [1976]—especially its first hour—is among cinema’s most poignant accounts of the immigrant experience,” writes Girish Shambu. “Historically, the best immigration cinema stages, in an astonishing multitude of ways, a divided state of being. By this I mean a condition not just limited to the subjectivities of specific characters—although it does find widespread expression there. In the most successful works, it infiltrates film form itself, often incarnated in structuring and stylistic strategies (breaks, doublings, oppositions) that echo the ‘split immigrant self’ and its experience in the world.”

Along with this remarkable essay, the new issue of Film Comment also features, as noted here and here,Ashley Clark on Dee Rees’s Mudbound,Holly Willis on Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne’s The Unknown Girl, and Amy Taubin’s conversation with Sean Baker about The Florida Project, reviewed in this issue by Cassie da Costa.

Also online:

- Michael Koresky on Wonderstruck, “which, like all of [Todd] Haynes’s films, is a thoroughly self-aware object, full of unexpected marvels.”

- Nick Davis’s conversation with Jane Campion about Top of the Lake: China Girl, which “explores the interlocking crises of multiple characters with stylistic precision and sociological sweep, its mercurial ambience combining suspense, tragedy, and the occasional but welcome note of mordant humor.”

- Eric Hynes on Raed Andoni’s Ghost Hunting and Jeff Malmberg and Chris Shellen’s Spettacolo, wherein “performance isn’t an artificial notion introduced from without, but an honest unveiling of what boils up from within.”

- Nicolas Rapold on Frederick Wiseman’s Ex Libris: The New York Public Library.

- Violet Lucca on Yuri Ancarani’s The Challenge.

- R. Emmet Sweeney on Jung Byung-gil’s The Villainess.

- Steven Mears on Noah Baumbach’s The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected).

- Nick Davis on Robin Campillo’s BPM (Beats Per Minute).

- Justin Stewart on Kevin Phillips’s Super Dark Times.

And Gina Telaroli presents a brief guide to viewing “movies that reside in the public domain” online for free.

More Reading

“Making The Devil’s Backbone [2001], I finally felt in command of my visual style, my narrative rhythm, and was able to work in a profound manner with my cast and crew to craft a beautiful genre-masher: a Gothic tale set against the backdrop of the greatest ghost engine of all—war.” That is, of course, Guillermo del Toro, and the snippet comes from the foreword to a book by Matt Zoller Seitz and Simon Abrams coming out in late November entitled, appropriately enough, Guillermo del Toro’s The Devil’s Backbone.

Woody Allen “is an astonishingly lazy director,” argues Christopher Orr in the Atlantic:

The most recent grist for this assessment comes from Eric Lax, an Allen acolyte, whose fourth book on the director, Start to Finish: Woody Allen and the Art of Moviemaking, is essentially an indictment framed as an encomium. Focused on the making of 2015’s Irrational Man, a film seen by few and liked by fewer, it functions as a third-person diary of a directorial indifference so extreme that one would expect it to have eroded the Allen brand by now. So how and why does Allen still enjoy his current level of prestige? Lax’s otherwise tedious account is a good occasion to explore that mystery, the key to which is something of a paradox: Allen’s reputation depends in no small part on the very indolence that undermines so many of his films.

“When you reach a certain age or fall ill, you can’t help but think about things like death and the past, including ghosts and dreams of the past,” Tsai Ming-liang tells Zhou-Ning Su at the Film Stage.

“The ideal of one nation under a movie theater has obvious appeal, but the dream that American movies are for everybody has always been a self-serving myth of what historically has been a white, male-dominated industry,” writes Manohla Dargis in a conversation with fellow New York Times critic A. O. Scott about the state of the movies in an all but hopelessly divided nation.

Paul Schrader’s Blue Collar (1978) “is, first of all, a studio picture that openly critiques both union corruption and the government’s sly attempts to disrupt legitimate union efforts—a rare subject for Hollywood.” K. Austin Collins at the Ringer: “But more importantly, it’s the rare American movie that sees racial difference as an essential weapon in that class fight. One of the only movies I can think of to surpass it in that regard is indeed Rocky, in which race straddles a fine line between subtext and text. In Blue Collar, race is the ultimate text—the ultimate point of difference.”

Writing for Vulture, Nicole Chung traces her search for tapes, scripts, anything that might be left of The Gallery of Madame Liu-Tsong, a mystery series that ran all of ten episodes in 1951 and starred Anna May Wong. “‘Liu Tsong’ was Wong’s Chinese name; she was the draw.”

]“When not greeted with indifference or merely mentioned in passing, Jean Epstein’s Les feux de la mer (1948) is frequently regarded as a strange and mismatching film, containing only a few sparks of Epsteinian poetry,” writes Cristina Álvarez López, arguing that it’s “been too easily dismissed as compromised and propagandistic, overshadowed by a didactic discourse diametrically opposed to the very notion of audiovisual lyricism that normally defines Epstein’s cinema. . . . Part of the charm of Les Feux de la mer depends on its heterogeneity—the play with fragmentation, multiple tones, surprising contrasts, and unpredictable shifts. Moreover, Epstein plunges into some ideas—geography, cartography, networks, and machine formations—that had been already sketched in previous films, but never taken as far as in this one.”

Also in the Notebook, David Cairns: “The real masterpiece of [Stanley] Donen's British period may in fact be Bedazzled (1967), but as a kaleidoscope of excessive visual tics, Arabesque [1966] should be shown in every film school: as smorgasbord of stylistic possibilities, or dreadful warning? That's not for me to say.”

James Churchill for Film International on Charles Vigor’s Gilda (1946) with Rita Hayworth: “No other film of the period (and few films, period) so meticulously explores the dark underbelly of sexual desire, the perverse manner in which the exploitation of others for personal pleasure can come to be advertised under the banner of love.”

“One of the advantages of watching films again on television is that, in their immense majority, they’ve all been made ten years ago or so and it’s therefore possible to see all the points they already had in common at the time,” wrote Serge Daney for Libération in 1988 (as translated by Laurent Kretzschmar). “That’s how we can already take enough stock to identify what makes Mad Max 2 a contemporaneous film to Diva. Where Beineix was trying to film emotions stored in objects stacked up in loft-like studios or in clichés engraved in memories by advertising, George Miller filmed feelings stored in diverse objects generously offered to all possible destructions along the roads and deserts of Australia.”

Also, “Buñuel’s films are like Buñuel, who is unlike anything.” And: “In both music videos and René Clair’s films there’s never enough time for any kind of build-up.” And then there’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: “It is later perhaps that the Leone of Once Upon a Time in America will suffer, when he will want to restore the classicism at the heart of a cinema that will by then have absorbed Leone’s mannerism beyond recognition. In 1966, it is different. Sergio Leone is both ahead of everyone and late behind everyone, he is therefore on time.”

James Slaymaker for Vague Visages on Abel Ferrara’s New Rose Hotel (1998) with Christopher Walken, Willem Dafoe, and Asia Argento.: “As a portrait of self-destructive masculine masochism and the terrifying unknowability of the desired Other (expressed through the relationship between the director and his real-life lover), New Rose Hotel is reminiscent of the collaborations between Josef von Sternberg and Marlene Dietrich.”

“Late Chrysanthemums (Bangiku, 1954) is among the sexiest of Naruse's Fumiko Hayashi-based pictures,” writes Craig Keller.

“While there are countless movies about stories of love lifted right out of the history books, the countless tales of same-sex love in the misty ages before the word ‘homosexuality’ was coined have barely been tapped,” writes Chad Denton in Bright Lights.

“The summer movies began when my daughters, who are in their forties now, were six and three,” recalls Calvin Trillin in his latest piece for the New Yorker. “For those early movies, we had only a silent Super 8 camera. On a cassette, I’d record narration that was often out of synch with the action on the screen. In other words, I was what passed for the screenwriter, and took the abuse associated with that lowly calling.”

Monday was Alain Resnais Day at DC’s.

In Other News

The Academy has announced that its Board of Governors has voted to present honorary Oscars to writer-director Charles Burnett (Killer of Sheep), cinematographer Owen Roizman (The French Connection), actor Donald Sutherland (Klute), and director Agnès Varda (Cléo from 5 to 7).

The International Federation of Film Critics (FIPRESCI) has named Aki Kaurismäki’s The Other Side of Hope as its choice for best film of 2017. The FIPRESCI Grand Prix 2017 will be presented to Kaurismäki at the San Sebastián International Film Festival on September 22.

Chaz Ebert has announced that Wim Wenders “will be honored at our annual Ebert Tribute Luncheon at the Toronto International Film Festival on Sunday, September 10th. I will be joining TIFF's Artistic Director, Cameron Bailey, in hosting the event for Wenders, a filmmaker whom Roger greatly admired.”

“Come October I’ll be leaving Europe after nearly two years, returning to USA for a long and perhaps final American sojourn,” announces Jon Jost. “As it’ll be for seven months or so, and dealing with the mundane stuff of peddling DVDs etc. will be too much hassle, I’ve decided to get all my work up online, VOD.”

“Legendary Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter is leaving the magazine in December, after 25 years on the job,” reports Gabriella Paiella for Vulture.

Goings On

Los Angeles. The American Cinematheque series Jeanne Moreau Remembered opens tonight as Amos Gitai presents his 2008 film One Day You’ll Understand and runs through Sunday at the Aero Theatre. Susan King talks with Kevin Thomas, “who reviewed films for nearly five decades at the Los Angeles Times and interviewed Moreau several times.”

London.Close-Up on Ruth Beckermann is on through September 24.

Venice.David Bordwell writes about this year’s Biennale College Cinema, which “supports creative teams making micro-budgeted first or second features.”

San Sebastián. Monica Bellucci and Agnès Varda “will be honored at the 2017 San Sebastián Film Festival with Donostia Awards for career achievement,” reports Emilio Mayorga for Variety. “John Malkovich will serve as the president of the main competition jury.”

In the Works

Jean-Luc Godard’s Le livre d'images, formerly known as Image et parole, is now in post-production and will be completed some time next year, reports the AFP. The French distributor Wild Bunch, which handled Godard’s Goodbye to Language (2014) and Film socialisme (2010), has not confirmed reports that the new film would be a reflection on the Arab world.

Newcomer Jeon Song-Seo is joining Yoo Ah-in in the cast of Lee Chang-dong’s Burning, an adaptation of Haruki Murakami’s 1992 short story, “Barn Burning,” reports AsianWiki. Shooting begins in a week or two.

“Armie Hammer is set to star in Participant Media’s On the Basis of Sex, which is based on the life of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg,” reports Anthony D’Alessandro for Deadline. “He’ll play husband Marty Ginsburg to Felicity Jones’s Ruth Bader Ginsburg as they team up to bring the first landmark gender discrimination case before the Supreme Court.”

“Even as New Line prepares for the Friday opening of its much anticipated adaptation of Stephen King's It, the company is moving toward a second movie based on the massive horror novel.” The Hollywood Reporter’s Borys Kit: “Gary Dauberman, one of the screenwriters on the new It, has quietly closed a deal to pen the screenplay for its sequel, and Andy Muschietti, who directed the new film, is waiting in the wings to return, although no deal is in place.”

“Benedict Cumberbatch will star in Gypsy Boy, a BBC Films-backed adaptation of Mikey Walsh’s best-selling memoirs,” reports Screen’s Tom Grater.

For more on projects in the works, see yesterday’s roundup.

Listening

On the latest Talkhouse Podcast, Barry Jenkins (Moonlight) and Eliza Hittman (Beach Rats) discuss “the challenges of shooting on a beach at night, how they both feared overly muscular actors might ‘ruin’ their films, and much more” (22’13”).

Director Jiří Menzel and Peter Hames, author of The Cinema of Central Europe, join Mike White and guest co-hosts Samm Deighan and Jonathan Owen, author of Avant-garde to New Wave: Czechoslovak Cinema, Surrealism and the Sixties, in the Projection Booth to discuss Menzel’s Closely Watched Trains (1966) (153’36”).

At Open Culture, Josh Jones goes chasing after the original Pink Floyd soundtrack for Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point (1970).

And Waxwork Records is releasing the original soundtrack for Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (1973) on vinyl today, “using a translucent red and opaque red mix, both of the same Pantone colors.”

For news and items of interest throughout the day, every day, follow @CriterionDaily.