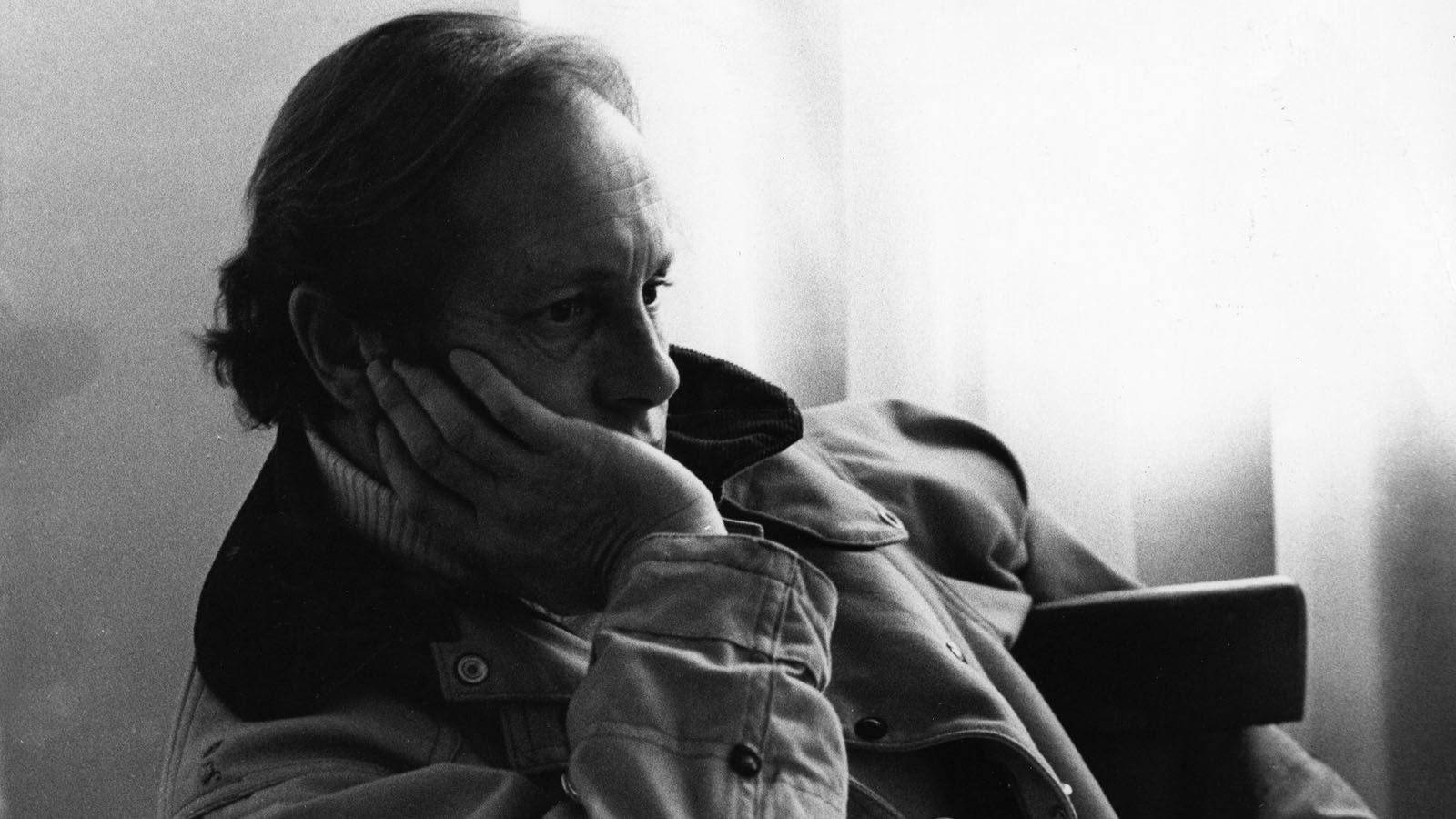

Nicolas Roeg, the Reinventor

Throughout a remarkable run that began in 1970 with Performance and stretched well into the 1980s, cinematographer-turned-director Nicolas Roeg approached every element of cinematic language as an opportunity to rethink it from the ground up and make it his own. Roeg, whose Don’t Look Now (1973) was voted the greatest British film ever made in Time Out’s poll of 150 critics and filmmakers, passed away on Friday at the age of ninety. In his remembrance for RogerEbert.com, Matt Zoller Seitz notes that his films “always pass the auteur test laid down by my colleague Godfrey Cheshire: once you’ve seen a few, you can identify one that you’ve never seen while observing it on a small TV from twenty paces away with the sound off.”

As a teen in the late 1940s, Roeg landed his first job “carting film cans up and down Wardour Street and making tea in the cutting rooms,” notes David Thompson in his obituary for Sight & Sound. “But it was during lunch hours when he was let loose on an editola that he discovered the magical properties of film, and how by running it back and forth he could play with time.” Not for nothing is Thompson’s 2015 portrait for the BBC program Arena titled Nicolas Roeg: It’s About Time. “More than any other English-language narrative filmmaker, Roeg apprehended Tarkovsky’s notion of ‘sculpting in time’ with the same radical freedom as the Russian director himself did,” writes Glenn Kenny, adding that “if Tarkovsky worked the long, flowing line, Roeg worked in jagged sometimes anti-linear lines, the better to evoke the dissociative effects the modern world has on individuals and their ideas of love and freedom. But not just that—it evoked something beyond the modern world, something eternal, the suddenness of what we still call fate, the potential suddenness of the end of it all.”

In a 1981 essay for The Movie, Jonathan Rosenbaum suggested that Roeg’s distinctive style was rooted in his work as a cinematographer. Having made his way up through the ranks at Borehamwood studios, serving as a clapper boy, loader, focus puller, and eventually camera operator, Roeg was a second-unit cinematographer on David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia (1962), shot Clive Donner’s Harold Pinter adaptation The Caretaker (1963), worked with Roger Corman on The Masque of the Red Death (1964)—a crucial collaboration, as editor and filmmaker Joshua Whitelaw demonstrates in the audiovisual essay embedded below—with François Truffaut on Fahrenheit 451 (1966), and with John Schlesinger on Far from the Madding Crowd (1967). It was while working with Richard Lester on Petulia (1968) “that Roeg can be said to have arrived at many of the rudiments of style and structure that characterize his own, subsequent films,” wrote Rosenbaum. “An essential part of this manner is a form of rapid and fragmented, kaleidoscopic cross-cutting between diverse strands in a narrative tapestry, an approach that creates meaning largely through unexpected juxtapositions. By and large, it is a wide-ranging, impressionistic method which can make a relatively simple plot multilayered and complex, and an already difficult plot a series of puzzles and mazes.”

After Petulia, Roeg codirected his next project with screenwriter Donald Cammell. Performance stars James Fox as a gangster who hides out in the basement of the Notting Hill apartment owned by a reclusive rock star played by Mick Jagger. As Rosenbaum notes, Roeg, who’d go on to cast David Bowie in The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) and Art Garfunkel in Bad Timing (1980), once told critic Harlan Kennedy that what he found “interesting about singers is that they all have the qualities of performers but they’re untouched in terms of acting.” Warner Bros. was appalled by Performance and held it for two years before releasing its own cut. In an excerpt at Little White Lies from his book marking the film’s fiftieth anniversary, Jay Glennie gleefully notes that the studio thought it was “buying into a film depicting the optimism and energy of swinging London; a new A Hard’s Day’s Night, complete with an accompanying album from the film’s star, the biggest rock star on the planet, Mick Jagger. Instead what they were handed was a heady cocktail of hallucinogenic mushrooms, sex (homosexual and three-way), violence, amalgamated identities, and artistic references to Jorge Luis Borges, Magritte, and Francis Bacon.”

Roeg cast his own son, Lucien John, in his debut as a solo director, Walkabout (1971). The boy and Jenny Agutter play a brother and sister abandoned to the harsh wilderness of Australia but saved by an aboriginal young man played by David Gulpilil. “Roeg uses the camera; wide shots, close-ups, colors and textures; to create a sense of unmediated perception as if we were seeing the world for the very first time,” observed the New York Times’ A. O. Scott in 2010. Matt Zoller Seitz suggests that Australian cinema’s “entire tradition of quasi-mystical, time-and-space-tripping outback dramas,” which would include Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) and The Last Wave (1977) and Fred Schepisi’s The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1978) and A Cry in the Dark (1988), “might have originated here.”

Few appreciations of Don’t Look Now are as heartfelt or as insightful as Norwegian director Joachim Trier’s (Reprise, Thelma). In an episode of Under the Influence posted just two months ago, Trier calls Don’t Look Now “an allegorical horror movie. On the one hand, it’s a very nuanced, naturalistic drama in terms of the performance and the way it’s shot.” It’s even “very gentle, very tender” in passages addressing the grief of a married couple (Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland) mourning the loss of their daughter. “On the other hand,” says Trier, “it’s a pure formalist experiment in how to cut in an associative way that’s closer to the human way of perceiving than the linearity of most films.”

The Guardian’s Peter Bradshaw recalls that Roeg once told him that when it came time to shoot the daughter’s drowning, each time she was lowered into the water, her father would race into shot and jump in to save her. “Anyone who has seen the film can understand,” writes Bradshaw. “I can close my eyes now and see Sutherland, crying out in agony, as he heaves his daughter’s dead body out of the water: it is an image as memorable, more memorable, than the famous sex scene or the supernatural encounters in Venice.” Speaking, though, of “the best sex scene in all of cinematic history,” as Trier calls it, novelist Jonathan Lethem wrote a memorable ode to this “brand sizzling into the viewer’s sexual imagination” in 2005.

Of all the personas rock chameleon David Bowie presented on-screen and on stage, none are as indelible as Thomas Jerome Newton, the alien who arrives on a mission to save his drought-stricken planet in The Man Who Fell to Earth. It’s “a singular, haunting sci-fi experience,” wrote Matt Noller for Slant in 2008, and just last year, Kim Newman, writing for Empire, noted that the film “buries its plot so deep that the audience, like Newton, is always struggling to find fixed points, but has never been bettered in its suggestion that the Earth is the strangest planet in the sky.”

Two Americans (Art Garfunkel and Theresa Russell) tumble into an erotically charged yet ultimately doomed affair in Cold War Vienna in Bad Timing, which was slapped with an X rating when it was released in the States and deemed “a sick film made by sick people for sick people” by the film’s own distributor, the Rank Organisation. “I was surprised and upset for the actors,” Roeg told Nick Hasted in the Guardian in 2000, when he also spelled out quite clearly what he was after: “You cannot intellectualize yourself out of obsession. You cannot cure yourself of it.”

Eureka, in which Gene Hackman plays a prospector who strikes it rich and then loses his mind, followed in 1982 and was met with a mixed response from critics and next to no response at all from audiences. “It’s a film that says being rich is horrible, that success leads to disaster,” filmmaker Bernard Rose says in Nicolas Roeg: It’s About Time. “It’s everything that’s not the dream . . . But it’s a very strong movie.” So, too, is Insignificance (1985), based on Terry Johnson’s play set on a steamy night in New York in 1953 when Albert Einstein, Marilyn Monroe, Joe DiMaggio, and Joseph McCarthy turn up in a hotel in New York.

By this point, “Nic’s supposed not to be firing on all cylinders,” says Rose, but Castaway (1986), Track 29 (1987), and the Roald Dahl adaptation The Witches (1989) would follow Insignificance. “You could stack those four films against fill-in-the-blank’s name,” proposes Rose, and “I could name ten directors who have huge reputations who haven’t made one film as good as those four.” But there’s no denying that Roeg was slowing down. He’d make two features in the ’90s and his last, Puffball, an adaptation of Fay Weldon’s novel, in 2007. Despite a strong cast led by Kelly Reilly and including Miranda Richardson, Rita Tushingham, and Donald Sutherland, Puffball was, on the whole, met with politely restrained criticism, even from his greatest champions. But as David Thompson emphasizes, Roeg’s major work remains ripe for discovery by a new generation. Six of them are currently playing on FilmStruck. And just this summer, the New Horizons Festival in Wroclaw presented a retrospective, and Thompson was there. “Every screening was full with a predominantly young audience most of whom had never seen his films before,” he writes, “and they were enraptured by them.”

For news and items of interest throughout the day, every day, follow @CriterionDaily.