Phil Solomon, “Alchemist of Cinema”

Since the family of the great artist and experimental filmmaker Phil Solomon posted news of his passing on Facebook this past weekend, hundreds of condolences and notes of appreciation have followed. Some come from former students—Solomon was a popular professor at the University of Colorado Boulder—while others are from virtual friends Solomon met on the platform where, as Kyle Harris notes in Westword, he enjoyed discussing “underground creative luminaries in music, film, art and literature.” Many comments, of course, are from those who have seen his films and video pieces, either at one of the two Whitney Biennials that have included his work or in any number of the permanent collections at the Museum of Modern Art, the Chicago Art Institute, the Oberhausen Film Collection, and several other prestigious institutions. “Although part of a long avant-garde tradition, Mr. Solomon makes films that look like no others I’ve seen,” wrote Manohla Dargis in the New York Times in 2005. “The conceit of the filmmaker as auteur has rarely been more appropriate or defensible.”

Solomon freely admitted in countless interviews that it initially took some time to develop an appreciation for that long avant-garde tradition. When he decided to study cinema at SUNY Binghamton in the early 1970s, he expected to be watching the great works of the new waves from Europe and the then-burgeoning New Hollywood. But the very first film that filmmaker Ken Jacobs screened on the very first day of class was Tony Conrad’s stroboscopic The Flicker (1966), and Solomon didn’t know how to even begin processing it. Where was the story, the narrative pull of the movies he’d grown up watching? “I didn’t know how to consider the screen as a formal rectangle with two-dimensional spatial tensions, rather than as a window to a daydream,” Solomon told Mike Plante in a 2006 interview. But Solomon eventually came around. While he also studied under Conrad himself, Ernie Gehr, Larry Gottheim, Dan Barnett, Saul Levine, and Peter Kubelka, Jacobs, he told Plante, “will always be my teacher, the source of all of it, the big bang for me.” The crucial turning point was a shot-by-shot breakdown of Stan Brakhage’s Anticipation of the Night (1958). As he told Federico Rossin in 2007, that was when “I began to grasp the concepts of visual metaphor and graphic analogies in the frame and on the cut.”

Another of Solomon’s oft-repeated admissions: His first films were outright imitations of Brakhage’s work. Solomon and Brakhage would eventually become close friends. They both taught in Boulder, and they collaborated on films such as Elementary Phrases (1994), Concrescence (1996), and Seasons . . . (2002). When Film Comment conducted a poll of critics, programmers, and teachers to come up with a list of the greatest avant-garde filmmakers of this century’s first decade, Solomon and Brakhage tied in fifth place.

But in the ’70s, Solomon was still forging his own style. The breakthrough was a 1980 black-and-white silent short called Nocturne. It “begins with a quavering line that slices across the frame like a searchlight, underscoring the two-dimensionality of the image,” wrote Manohla Dargis. “Like the first stroke of a painter’s brush, this line is merely a beginning, however, and soon gives way to swirling grain, dancing lights and the human figures that crowd Mr. Solomon’s work like fugitives.”

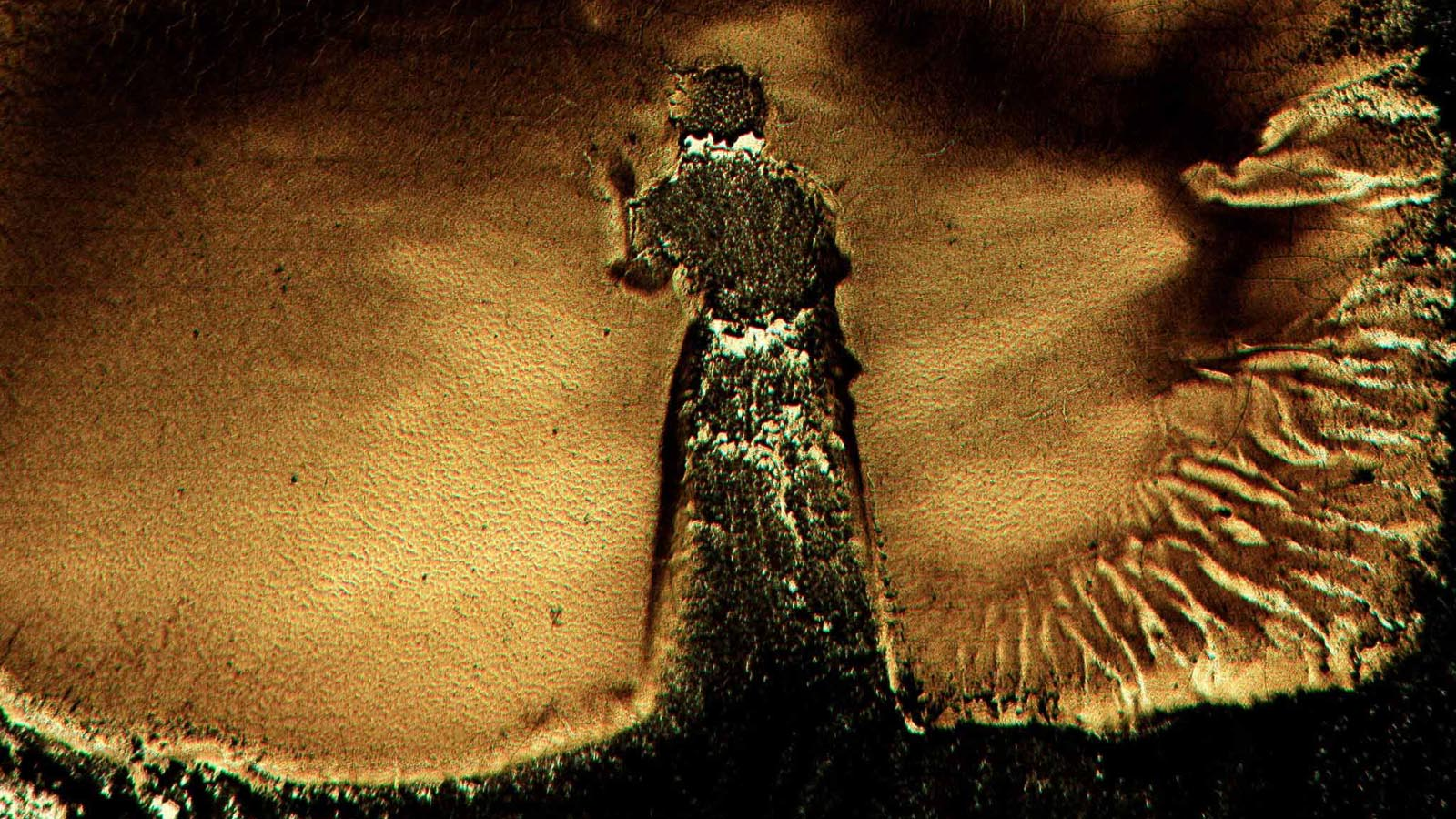

Films such as the Twilight Psalms (1999–2003) and The Snowman (1995) “are composed of photographic imagery in varying states of aggravated decay, with recognizable figures and objects emerging and resubmerging into bubbling cauldrons of film grain, thick chemical impasto, and an almost sculptural build-up and breakdown of emulsions,” wrote Michael Sicinski in Cinema Scope. Talking to Doug Cummings in 2013, Solomon described his process during this period. “I use several techniques, but all of them are aspects of optical printing, which is rephotography on a machine. Sometimes, I’m stressing the surface of the film with post-processing. Other times I’m exploiting something that’s already happened, which is to say the footage was molded or in a flood or something like that; it’s footage I found that was ruined and I amplify the textures.” He was open to serendipitous discoveries—but only to a certain degree. As he told Rossin, he liked “being surprised by what Stan called the ‘angels of film’ when they visit, but I am, alas, a bit of a control-freak and would love to be able to really work with emulsion with the precision of Vermeer.”

When Chris Kennedy programmed a Solomon retrospective in 2015, he noted that scholar Tom Gunning had grouped the filmmaker “with some of his contemporaries (including Lewis Klahr, Peggy Ahwesh, and Mark LaPore) in an essay titled ‘Towards a Minor Cinema,’ which acknowledged these artists’ turn away from the romantic ego of psychodrama (à la Stan Brakhage), the conceptualism of structural film (à la Michael Snow), and the political theory of New Narrative (à la Yvonne Rainer) to a more expressive lyricism of image and montage.” In 2012, David Bordwell noted that “Solomon agrees that he joined this deliberately ‘minor’ filmmaking tradition, exploring the fine grain of imagery and what Gunning calls ‘submerged narratives.’”

But that doesn’t make his work thematically minor. The word “alchemy” often appears in association with Solomon’s films—see Tony Pipolo, writing for Artforum in 2010, for example—and in an interview with Solomon for Issue magazine, David Grillo began by declaring, “I’ve often called you an alchemist of cinema.” Solomon responded by pointing out that the “metaphysical inklings to be found in my work are not so much about any kind of personified god or any specific kind of religion, but more along the lines of, say, the New England Transcendentalists.” In terms of influence—besides Brakhage, of course—Solomon told Plante that his films “seem much closer in their temperament, ideas, and tendencies to the form and content of certain—somewhat hermetic—poets like Emily Dickinson, John Ashbery, Wallace Stevens, and Jorie Graham. Or textural narrative painters like Albert Pinkham Ryder, Francis Bacon, and Anselm Kiefer. Or the polyphonic re-imagined, and re-remembered aural American narratives of Charles Ives. Or the ambiguous, lush, and mysterious ambient landscapes in the organic electronic music of Brian Eno.”

Solomon has referred to one of Ives’s major compositions, The Unanswered Question, as “the national anthem” of a piece originally commissioned as a multi-channel installation for the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington. American Falls (2000–2012), which has since traveled as a triptych, “offers a richly allegorical account of America’s rise and fall through a torrent of intricately distressed celluloid sourced from a disparate array of films and newsreels, and featuring everyone from Amelia Earhart to King Kong to Robert Oppenheimer to Charlie Chaplin,” wrote Leo Goldsmith at the top of his interview with Solomon for the Brooklyn Rail in 2012. “Through these distorted icons of the past, and amid waves of exquisitely mixed found sounds, Solomon locates a critical meta-history of the American mythos at the intersection of film’s decay and digital media’s ascendancy.”

Within a few years, Solomon was exploring the pixelated textures of digital media in a series of works that began one night as he and his close friend and fellow filmmaker Mark LaPore were wandering the virtual world of Grand Theft Auto. Together, they made Untitled (for David Gatten) in 2005, and when LaPore died shortly thereafter, Solomon created a series of works, In Memoriam (Mark LaPore), that includes Rehearsals for Retirement (2007) and EMPIRE (2008/2012), a nod to Andy Warhol’s landmark of structural cinema, Empire (1964). For Michael Sicinski, Solomon’s earlier works on film “are not nearly as disturbing as Untitled and Rehearsals. Yes, they thrust our eyes into fragility and dissipation, but there is a brute materiality at work. The celluloid, the shadows of a photographed world, even the thick, pulsing seas of decay that threaten to overtake them—these are all elements of the tangible universe. The new works, in part, replace chemistry with code, and in the process they seem to slip further away from us.”

In 2013, Young Projects, an art space in Los Angeles devoted to the moving image that has since closed, presented an exhibition of Solomon’s work, and the video documentation offers an introductory sampler of the various stages in his career: