8 ½: When “He” Became “I”

The typical midlife crisis, to which we all fall victim in some major or minor degree, came to Fellini with a slight delay. On the twentieth of January, 1960, the day of his fortieth birthday, he was, in fact, too deeply engaged in the completion of La dolce vita to worry about anything else.

Only a few months later, the maestro was confronted by a dilemma he never expected to face: what to do next. Until then, Fellini had always nurtured new ideas that would naturally take over his time once the project under way had been completed; he had never experienced a real break between these two moments of the creative process. But for the movie about Via Veneto, the effort and emotions he had invested were such that, once the great clamor of critical acclaim and polemics had quieted, Fellini felt the horror of an inspirational void.

He had been telling himself for a while, almost superstitiously, that a director’s artistic life lasted ten years, after which one ended up repeating oneself; he would quote such cases as René Clair, G. W. Pabst, Jean Renoir, Fritz Lang, and others. The ghost of creative barrenness appeared to him, almost poisoning the pleasure of a moment that could have otherwise been magic, and became a sort of obsession, so much so that he considered making it the theme of his new movie.

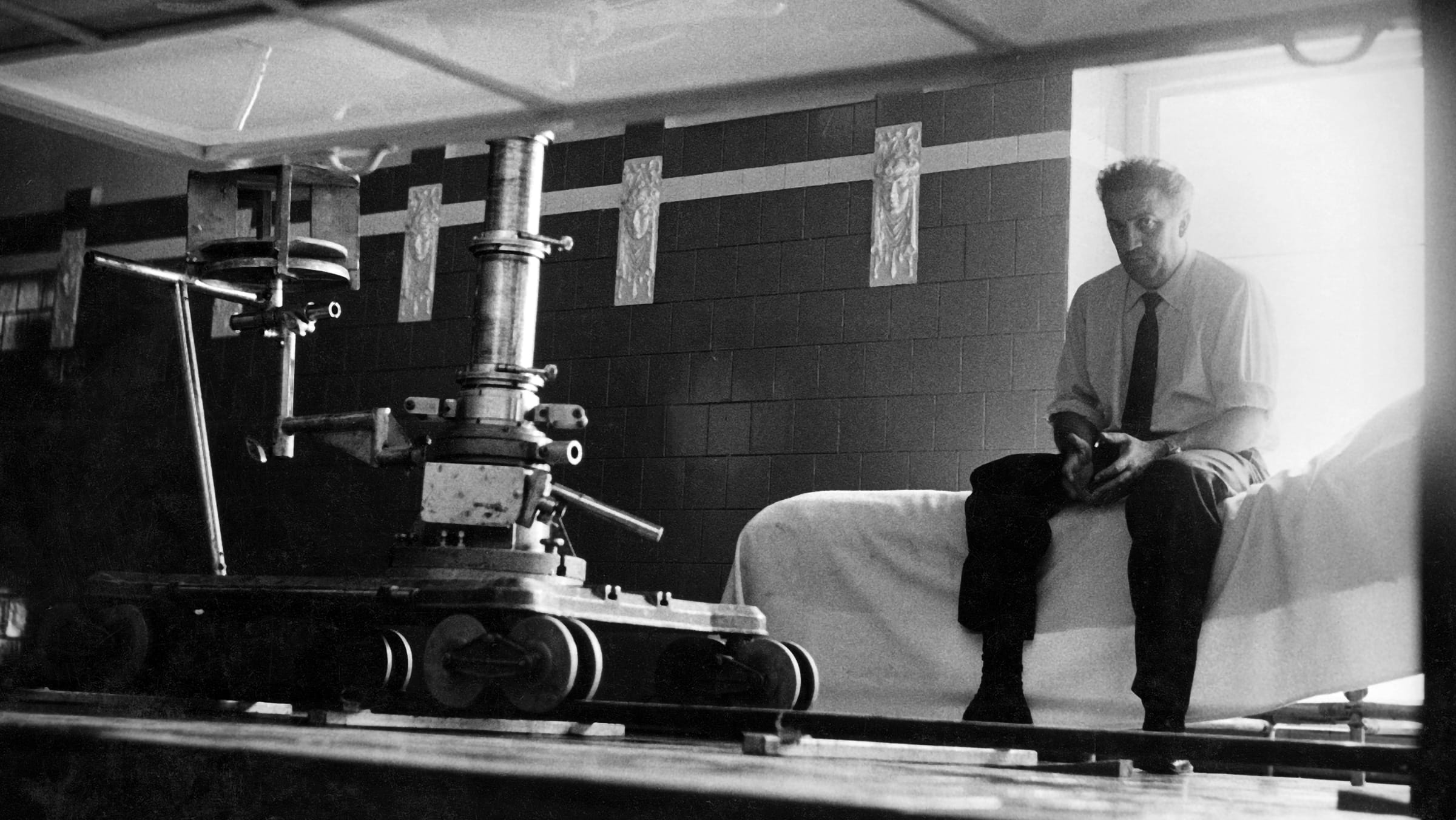

He started working with his usual team of screenwriters: Tullio Pinelli, Ennio Flaiano, and Brunello Rondi. Federico handed me a script to read. I can’t recall if the first draft of what was to become 8 ¹ ⁄ 2 had a title. I know that Flaiano had proposed La bella confusione. Meanwhile, the director, perhaps in order to dispel a certain air of pessimism lingering about the project, insisted upon defining the movie as “comic.” Needless to say, on set he only sporadically remembered his own definition, and even then turned this so-called comicality into irony or the grotesque. Personally, I found very little solace reading those pages recounting, in a rather tormented fashion, the crisis of a writer unable to complete his novel and caught in an embarrassing sentimental web between wife and mistress. The many autobiographical implications, even though hidden between the lines, were evident, as they had been previously in La dolce vita. This time, however, the amalgamation of fantasy and reality didn’t feel as accomplished. The problem was that Fellini had decided to make his protagonist a writer, a character he could not clearly picture emotionally.