Love Wins

The London Film Festival wrapped this past weekend with the announcement that Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Evil Does Not Exist had won the Best Film award in the official competition. The British Film Institute then immediately segued into Cinema Unbound: The Creative Worlds of Powell and Pressburger, a series of screenings and talks taking place all across the UK through the end of the year and taking us straight to the first of this week’s highlights.

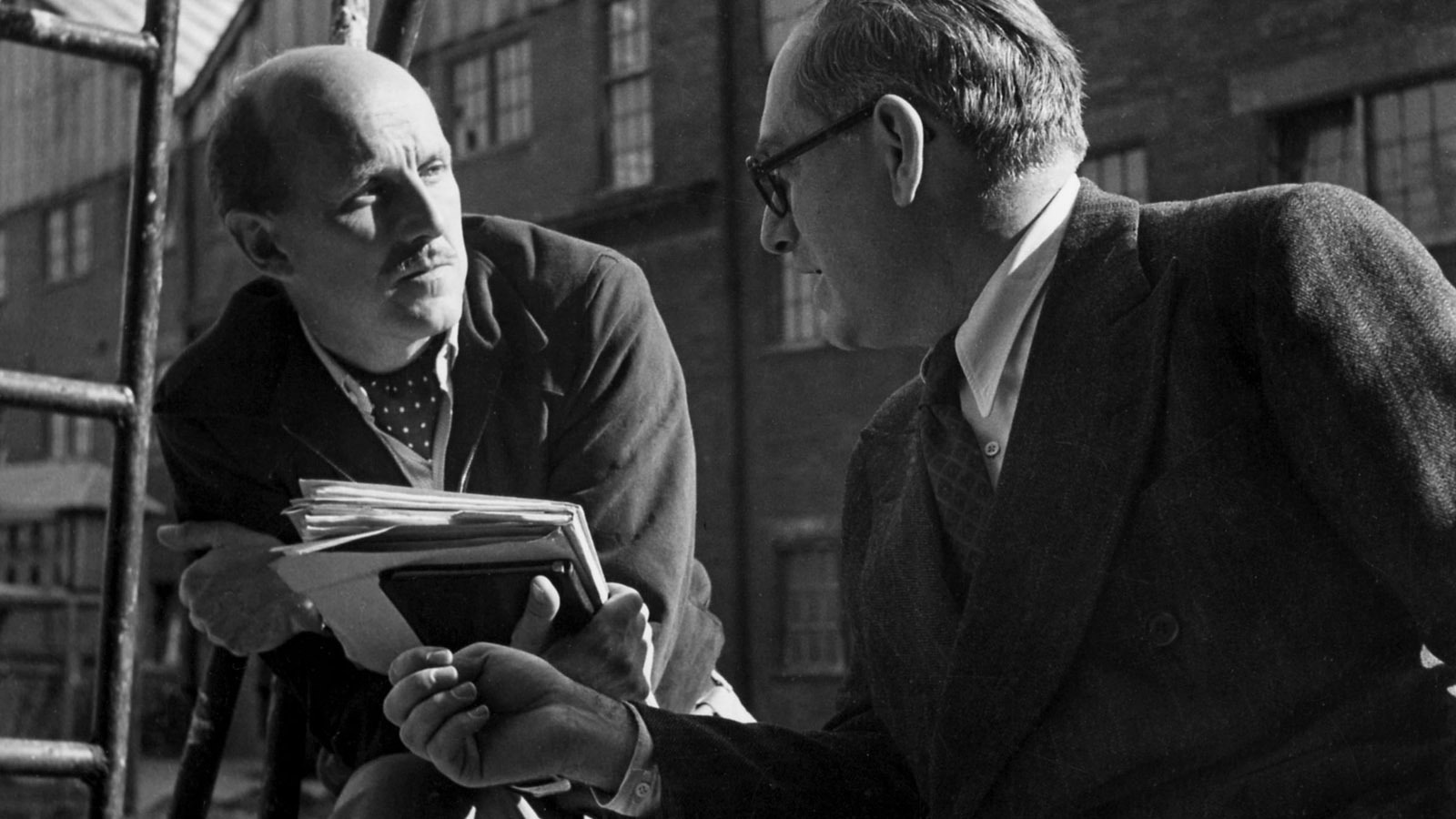

- Michael Powell, a British filmmaker through and through, and Emeric Pressburger, a Hungarian Jew who fled the Nazis, made films together that blended “stiff-upper-lipped Englishness, Albion mysticism, and mittel-European sophistication,” writes the Guardian’s Xan Brooks. “I have loved these dramas for years, sometimes in spite of their old-school politics and, more recently, precisely because of them.” Writing for the BFI, Philip Concannon delves into the restoration of Peeping Tom (1960), the film Powell made three years after parting ways with Pressburger. At Little White Lies, Lillian Crawford asks Thelma Schoonmaker, Powell’s widow, which film she’d like to restore next. Gone to Earth (1950) is her answer, “but there’s all kinds of problems with that. Selznick cut into the original version so we’re missing frames and things, so that’s going to be a really hard one. But it’s beautiful.”

- Schoonmaker has been editing Martin Scorsese’s films since 1980’s Raging Bull, and their latest collaboration, Killers of the Flower Moon, opens this weekend. As Angela Aleiss points out in the Hollywood Reporter, the story the film relates was first told on-screen in Tragedies of the Osage Hills (1926), which opened in Oklahoma “just four months after the arrests of William King Hale, Ernest Burkhart, and John Ramsey—played by Robert De Niro, Leonardo DiCaprio, and Tay Mitchell, respectively, in Scorsese’s film—for the horrifying murders of several dozen or more Osage Indians over their oil headrights.” Tragedies is “one of the thousands of silent features shot on nitrate stock that did not survive,” and while producer James Young Deer was hailed as “Hollywood’s first Native American filmmaker,” his true identity, like his roller-coaster career, was a bit of a muddle.

- Revisiting Robert Bresson’s The Devil, Probably (1977) at Crooked Marquee, Sean Burns observes that “if you find your way onto Bresson’s frequency, his films can feel like they’ve transcended cinema’s inherent artifice and found a purer, more exaltedly spiritual mode of storytelling. There’s a reason Paul Schrader has made an entire career out of remaking Pickpocket and Diary of a Country Priest.” For the Smart Set, Greg Gerke writes about taking a while—several years, in fact—to tune into that frequency. “None of the theatrics of most films are available in Bresson,” he notes, “because in some ways Bresson’s characters, along with Dreyer’s and Cassavetes’s, are the most inscrutable in motion pictures—maybe since their creators are the best believers in suggestion.”

- The New York Times has a nicely designed feature marking fifty years since the release of William Friedkin’s The Exorcist. Along with a sample of 1973 headlines blaring the breaking news that audience members were fainting and losing their lunches, there are three essays. Jason Zinoman explains why Friedkin’s version “hits harder” than novelist and screenwriter William Peter Blatty’s. Manohla Dargis considers The Exorcist as a “women’s picture” that brings Mildred Pierce (1945) to mind. And Erik Piepenburg proposes that the film is “subversively queer” in that “it’s about a child consumed by an entity that the church is called on to excise, a hideous intersection of metaphorical queerness and real trauma that sounds a lot like conversion therapy.”

- The new Gagosian Quarterly features a beautifully multifaceted essay by Fiona Duncan on Personal Best (1982), the directorial debut of screenwriter Robert Towne (Chinatown) and her favorite film. “Towne’s gift, when he was allowed to exercise it, was scripting melodramas that reveal themselves in a rewatch,” writes Duncan. “Embedded in historical contexts, his sequences of cause and effect are lifelike, with monumental changes accruing through obscure little gestures and twists such that it’s only in retrospect that you can piece together something of what happened.” Mariel Hemingway and Patrice Donnelly star as track-and-field athletes, and their coach (Scott Glenn) “suggests that sport is a history of violence,” but “Personal Best rebuts him: love wins.”