Masculin féminin

On Wednesday, Cannes confirmed that Paul Verhoeven’s Benedetta will finally premiere in competition on July 9, the same day it opens in theaters in France. Producer Saïd Ben Saïd first announced the project based on Judith C. Brown’s 1986 book Immodest Acts: The Life of a Lesbian Nun in Renaissance Italy four years ago, and Benedetta was on track to premiere at Cannes in 2019 until Verhoeven’s hip surgery delayed postproduction. Then, of course, the 2020 edition was cancelled. With French movie theaters scheduled to be fully reopened by June 30, plans for Cannes’ seventy-fourth edition, running from July 6 through 17, are still very much on.

- The new Senses of Cinema opens with a selection of twenty-three relatively brief responses to the question, “What will become of cinema?” The Mar del Plata Film Festival gathered more than seventy replies in all late last year from filmmakers, programmers, and critics around the world, resulting in a volume that artistic director Cecilia Barrionuevo describes as “a strange manual—halfway between a cinephile self-help book and an international manifesto.” The new Senses also features essays on the late cinematographer Giuseppe Rotunno, George Romero, and Agnieszka Smoczyńska as well as interviews with Queena Li and Ana Vaz and notes on films by Hiroshi Shimizu and Gillian Armstrong. And there are three additions to Senses’ collection of primers on great directors: Spike Lee, Sidney Lumet, and Nobuhiko Obayashi.

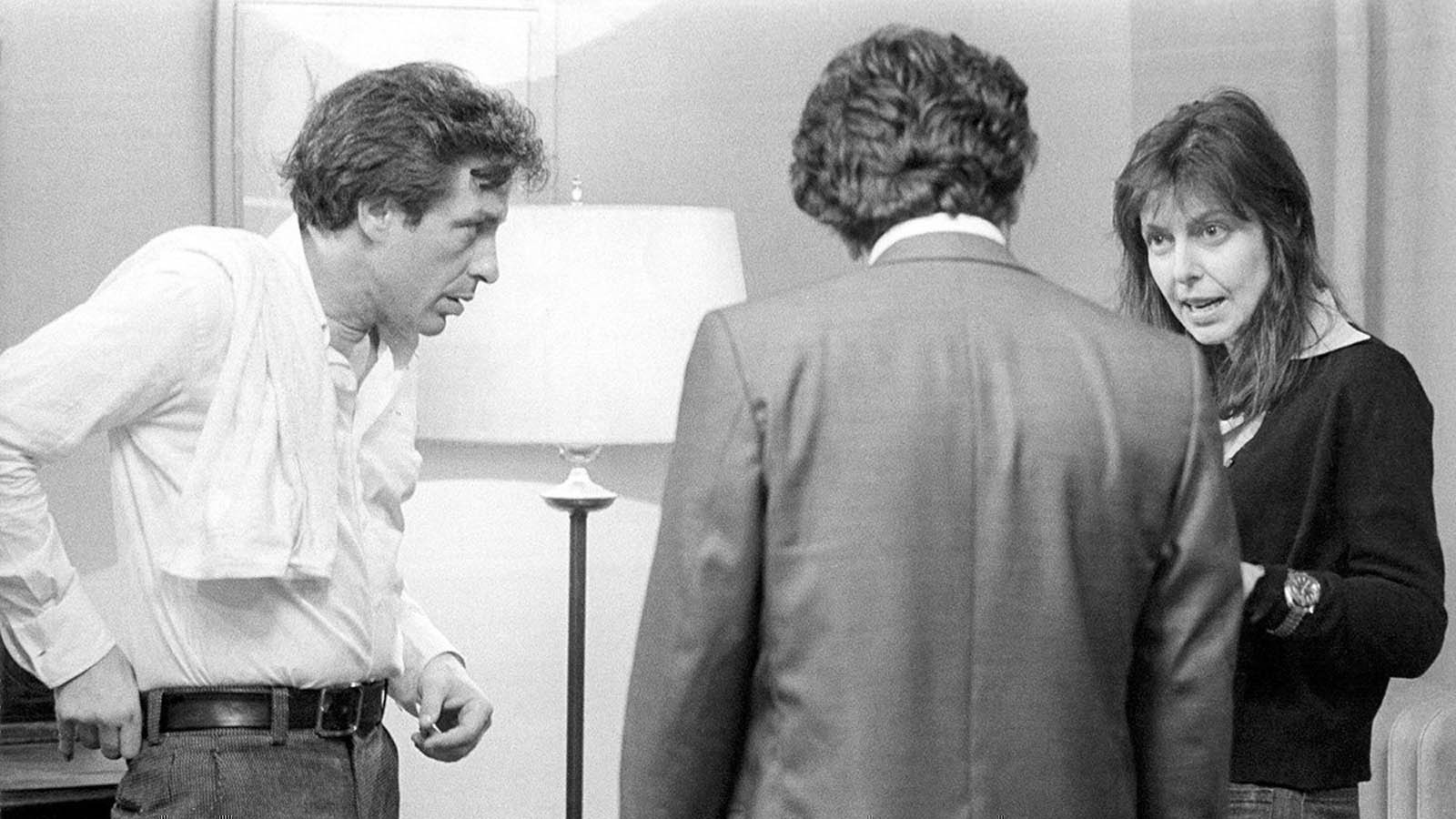

- The TCM Classic Film Festival is on through the weekend, and Letterboxd has called up Mike Nichols biographer Mark Harris, who will be presenting the 1996 American Masters documentary Nichols and May: Take Two, and TCM host Alicia Malone for a conversation that touches on movies they fell for when they were younger, lockdown discoveries, immigration stories, “problematic faves,” and of course, Elaine May. For newcomers, Harris recommends A New Leaf (1971), but Malone “would say Mikey and Nicky [1976] straight out of the gate” because “I love subverting expectations of what a female director can do and that is such a masculine movie.”

- On a recent New York Times Popcast, Jon Caramanica spoke with Simran Hans and Caryn Ganz about the recent glut of pop star documentaries, and you can bet that Madonna: Truth or Dare (1991) came up. It was the highest-grossing documentary of all time until Michael Moore came along in 2004 with Fahrenheit 9/11. “What’s most striking about Truth or Dare thirty years later,” writes Matthew Jacobs, introducing his oral history for Vulture, “is that, unlike the subjects in today’s pop docs, which tend to emphasize solitude and struggle, Madonna looked like she was having a ball. In the vein of the Old Hollywood luminaries she idolized, she adores being famous; she’s good at it.” Director Alek Keshishian had been hired to document the Blond Ambition tour but discovered the real story as he watched a pop star play den mother to a troupe of young, mostly gay dancers. “As Warren Beatty said,” the director tells Jacobs, “‘You don’t do this. This is not how you create stardom.’ That’s why Truth or Dare worked. No other star had done that yet. Once Truth or Dare did it, you kind of can’t do it again.”

- Liza Minnelli turned seventy-five in March, and former festival programer Shannon Kelley (Sundance, Outfest, UCLA) has written an appreciation for Film Quarterly. “Over the years, between projects, she has publicly outrun the fates (love woes, health scares, addiction) with a regularity that makes her existence seem cyclical, rather than linear,” writes Kelley. Minnelli “always, always brought the crazy . . . with a Z. Not just in terms of her rag-doll look, or her personal difficulties. The craziness that mattered was of a sweeter, more sincere kind; a fierce belief and hope (you can see it in her eyes) in the stardust of the theater tradition; of craft and legacy. That madness can be dialed up or down; volume and size are not its only registers.”

- In Paris Calligrammes, German artist and filmmaker Ulrike Ottinger looks back on the years she lived and painted in the French capital, 1962 to 1969. “The Ottinger oeuvre is a combination of epic documentaries, fantastic voyages, and ethnographic inquiries,” writes J. Hoberman in the new issue of Artforum. Paris Calligrammes “encompasses them all.” Ottinger “conjures a gray and drizzly wonderland where Jean Rouch and Marceline Loridan might be discovered deep in café discussion. Isidore Isou declaims, Juliette Gréco chanteuses, Isadora Duncan’s eccentric brother strides the streets in a toga of his own design. In some snapshots, the young painter herself appears as a deadpan participant in various soirees.” When she returned to Germany and picked up a camera, Ottinger became, “as film critic Dave Kehr once put it, ‘a one-woman avant-garde opposition to the sulky male melodramas of Wenders, Fassbinder, and Herzog.’”