Summer Travels

Share

Some of the best reading this first week in August has taken us to Japan, India, Oregon, Portugal, and an Afrofuturistic Africa:

- Moeko Fujii, who wrote an essay for us back in April marking the centenary of the birth of Toshiro Mifune, writes in her latest newsletter about Setsuko Hara, who would have turned one hundred in June. When she died in 2015 and was over and again remembered for her “eternal smile,” Fujii thought instead of how Hara “made us feel when she let it fall. This look of hers is a species of side-eye,” which is “not as unambiguous, committed, or as adolescent as an eye roll—it’s an ocular seismograph for something deeper, more fleeting. The thrill of witnessing a side-eye is that of chasing fireflies: of catching the elusive dart, the streak of bright-green.” Hara is “most expressive when she’s not moving her mouth, her face, or her body at all. Her eyes settle, and in that movement, she spells a certain inner destruction—usually for a man—but sometimes for herself. There’s a granite in those glances which we can’t help but love her for, perhaps because we feel its absence in our contemporary stars, of a restraint that will not yield.”

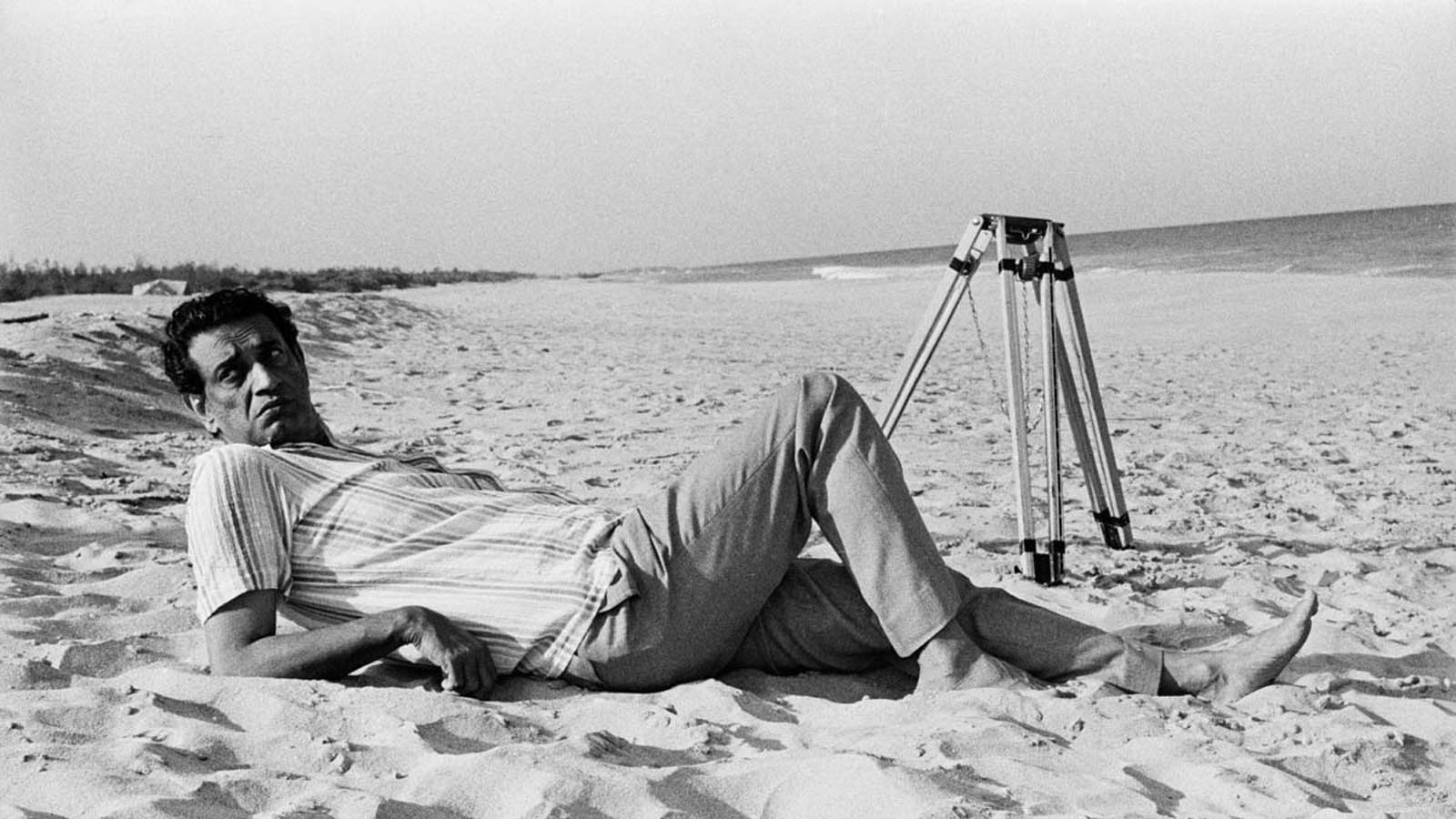

- Satyajit Ray was a tall man. Six feet, four inches. Writing for Popula, Mahdi Chowdhury notes that, during his lifetime, western publications often “indulged in writing about Ray as a physiognomic curiosity. Their encounters with Ray’s actual body resulted in a discernible style of writing and gaze that expressed, at best, a kind of overfamiliarity with the director and, at worst, exaggeratedly colorful and exoticized renderings of Ray as a sort of uniquely racialized spectacle.” But “for the intimates in Ray’s life, his height was not an animal curiosity . . . rather it was a token of his identity, as exceptional and incongruous as it was familiar.” Following a brief look at “the trope of the ‘short Bengali’” as “a stereotype of colonial pedigree,” Chowdhury writes: “To my mind, Ray’s height is one of those rare incidents of cosmic appropriateness. How perfectly suitable and apt for a soaring artistic spirit to embody a like physical stature.”

- Julian Smith tells the story in Alta behind one of the most famous and certainly the most expensive shots in the history of the silent era. In a crucial sequence in Buster Keaton’s The General (1926), a burning bridge collapses, dumping a steam-powered train into the river thirty-four feet below. In the weeks and months leading up to the filming of that make-or-break shot—it was a real train, so once it was wreaked, that was it—the people of Cottage Grove, a tiny logging town in Oregon, and Keaton’s crew, which had arrived with “eighteen freight cars full of Civil War cannons, stagecoaches, prairie schooners, props, cameras, and over 1,200 costumes,” had played baseball and fought fires together. When the day came to crash the locomotive, thousands came to watch: “Some 600 autos trundled along narrow mountain roads, and two special trains ran to the site.” Keaton got his shot—but there was still a battle scene with 500 extras to get in the can.

- Some Letters Make the Night Last a Moment Longer is the title of a project curated by Sergi Álvarez Ríosalido for La Casa Encendida, a social and cultural center in Madrid. Since early July, filmmakers Mariano Llinás and Matías Piñeiro; Valentina Alvarado and Nazli Dincel; and Antonio Menchen and Rita Azevedo Gomes have been exchanging filmed correspondences, and they’ll carry on doing so through the end of September. Mubi is currently presenting an Azevedo Gomes retrospective, and in the Notebook, Olaf Möller writes about the influence of Manoel de Oliveira and the late painter Luís Noronha da Costa on her work, both as a filmmaker and a programmer at the Cinemateca Portuguesa. These influences are “always there,” he writes, but “they’re not the key to her cinema. For there’s something to her films very much her own.” The “word that describes best the particular beauty of Rita Azevedo Gomes’s films in toto” is “serenity.”

- In the week since Black Is King, Beyoncé’s third visual album after Beyoncé (2013) and Lemonade (2016), appeared on Disney+, writers of all stripes have been weighing in, and most of them are more or less on the same page: Obviously, this reimagining of The Lion King: The Gift, Beyoncé’s companion album to last year’s twenty-fifth anniversary update of Disney’s The Lion King, is must-see viewing, but it’s not likely to have the cultural impact Lemonade did four years ago. The New York Times has gathered first impressions from Wesley Morris, who finds “a real Baz Luhrmann zaniness working here,” critics Jon Pareles (pop), Vanessa Friedman (fashion), Jason Farago (art), and others. In ARTnews, Alex Greenberger lays out a guide to the codirectors, painters, sculptors, and designers Beyoncé is working with here. In the Washington Post, Kinitra D. Brooks, coeditor of The Lemonade Reader: Beyoncé, Black Feminism and Spirituality, writes: “Afrofuturism urges Black people to recover their pasts in order to create their own futures. Black Is King imagines what it looks like to be there, whole and healed.” But writing for the New Yorker, Lauren Michele Jackson, author of White Negroes: When Cornrows Were in Vogue . . . and Other Thoughts on Cultural Appropriation, suggests that “someone like” Terence Nance (Random Acts of Flyness) might have made a more “multidimensional case for a contemporary Blackness that is not necessarily beholden to the legacy of a pre-colonial continent.” For Craig Jenkins at Vulture, Black Is King is “the culmination of everything Beyoncé has learned in film since breaking out in Carmen: A Hip Hopera,” the MTV musical directed by Robert Townsend in 2001.

For news and items of interest throughout the day, every day, follow @CriterionDaily.