In the House of Cinema: A Conversation with Mia Hansen-Løve

Mia Hansen-Løve makes delicate, graceful films about overpowering emotions. After beginning her career in front of the camera, acting in Olivier Assayas’s Late August, Early September (1998) and Les destinées (2000) as a teenager, she transitioned to directing at the age of twenty-six with All Is Forgiven (2007), the first in a series of quietly devastating family dramas that established her as one of French cinema’s most sensitive young storytellers. In all of her work, she captures people in turbulent moments in their lives, and her often autobiographical character studies bring subtlety and insight to the exploration of grief, self-discovery, and youth’s fleeting pleasures.

This month on the Criterion Channel, we’re celebrating Hansen-Løve’s work with a series of three of her features: Father of My Children (2010), the story of a producer in crisis; Goodbye First Love (2011), a tale of romantic heartbreak; and Things to Come (2016), a chronicle of one woman’s post-marital awakening. In our wide-ranging conversation, she talked about the life-affirming pleasure she gets on set and how she hopes to build a filmography in which all the parts speak to each other.

Was there a specific time in your life that was most crucial to shaping your love of cinema?

The first was when I was very young. I would watch what was available to me at my house or at my grandmother’s, like the films of Hitchcock. Then there was the moment when I started going to the cinema because I wanted to, because I was curious. That’s when film started to really mean something to me. I was about sixteen or seventeen and had just acted in a movie for the first time. I’d go see films by Bresson, Bergman, or Jacques Doillon, and then I’d watch Rohmer films at home.

I remember seeing my parents sitting on the bed watching a Rohmer film and having some kind of argument about it—my mother would be defending the characters, and my father would be making fun of them, tenderly. The way they discussed it was actually like a scene in a Rohmer film. I suppose that made me understand the connection that can exist between films and real life, and that cinema doesn’t have to represent a fantasy world. That was an important moment for me, realizing that you can make films with the life that’s in front of you.

How did you make the transition from acting to directing, and what did it feel like when you became the one behind the camera?

My acting experience was minimal—I was only in two of Olivier’s films, and not in the main parts—but what was crucial for me was experiencing the intensity and the magic of being on set. I was seventeen and nineteen when I acted in those films, and that was when I began to understand why cinema was the thing I wanted to do. It had to do with the fact that in cinema you can turn something abstract into something real. And you can turn melancholy into pleasure.

The intensity on set is something you cannot get from writing. What I learned from the experience of acting was not so much about the acting itself but about how a team works. I wanted to get back to that feeling, but I wasn’t trying to become an actress. I felt much more comfortable on the other side of the camera, and the fact that I could express myself through the bodies of other actors who would inhabit my feelings was so freeing.

When it comes to the films and filmmakers you love, how do you think about their influence on your work?

I wouldn’t say, like some directors do, that there was a certain film that led me to make this or that. But I would say that there are films whose language and storytelling have become a part of my world, and that it’s thanks to their existence that I became a filmmaker. It’s easy to see the connection my films have to Rohmer and Truffaut, but it’s also true that I’ve been obsessed with filmmakers whose influence on me can’t necessarily be seen as clearly, like Melville or Visconti or Michael Mann. I never try to show references in my films. It’s just not the way I work. The more I admire a filmmaker, the more I want to find my own language.

Do you tend to react to movies instinctually and viscerally, or do you find that you intellectualize them pretty quickly?

The two are connected. I process my emotions on an intellectual level. I can cry and become emotional over very stupid, empty things, and I can also cry over masterpieces, so emotion means both a lot and nothing. What’s interesting to me is understanding what kind of emotion it is and then investigating whether that emotion is valuable or not. In my films, I’m trying to provoke those emotions that I value, not ones that can come as quickly as pressing a button.

Father of My Children

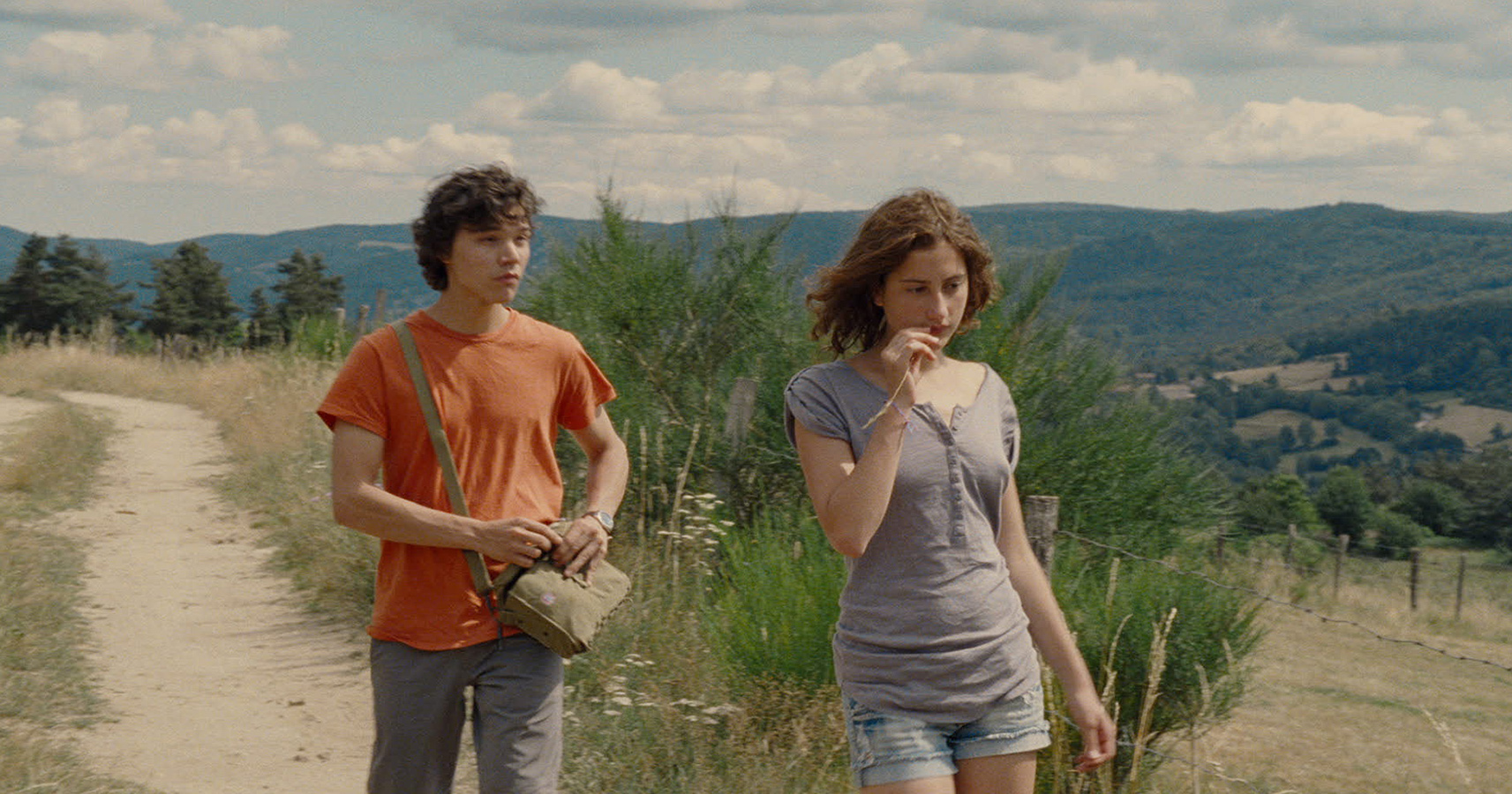

Goodbye First Love

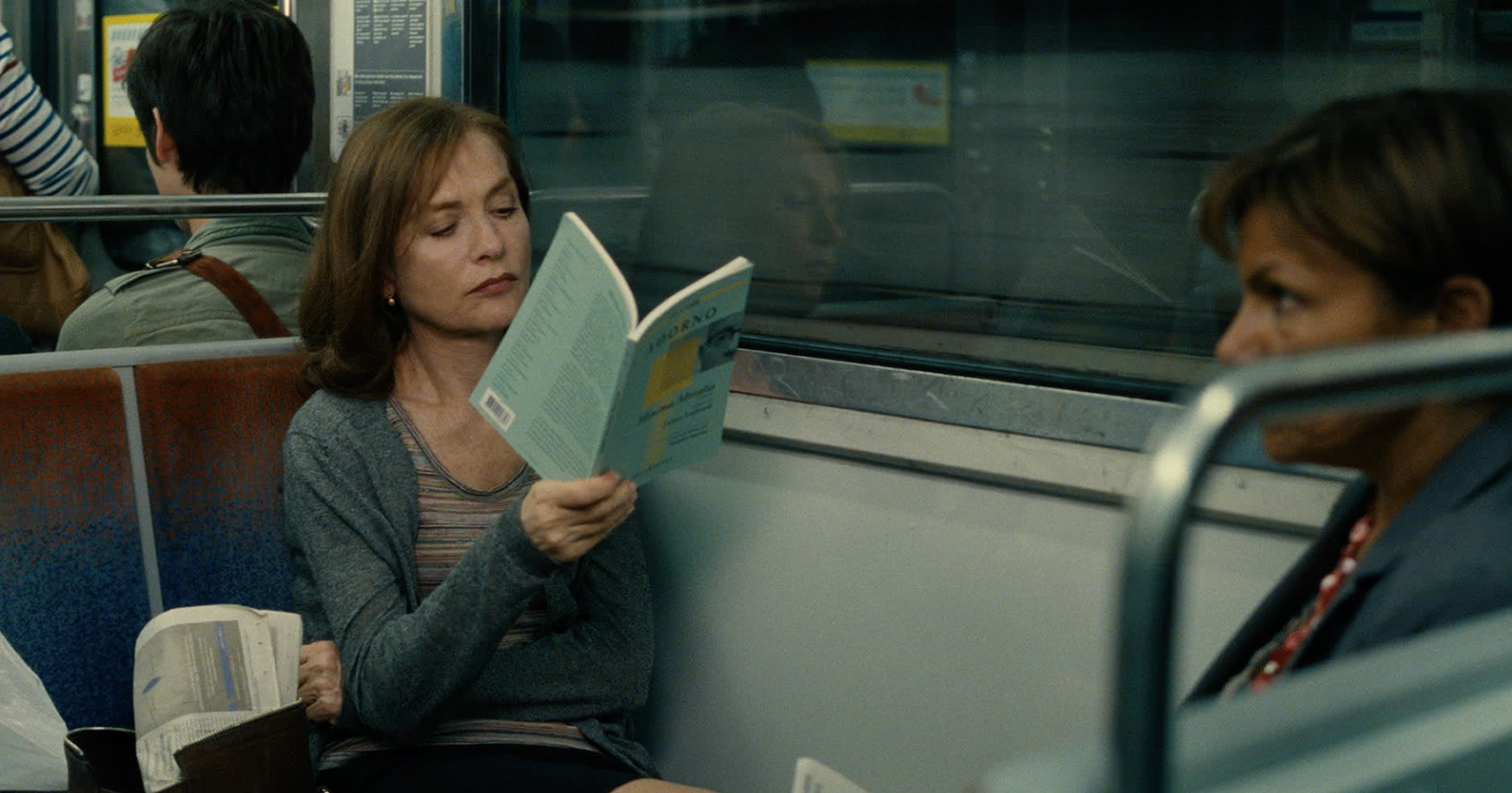

Things to Come