Hidden Gems of the 2010s

The recent flurry of best-of-the-decade lists has many of us looking back on our favorite movies of the era—including ones that may have been unjustly overlooked. At a time when the increasing number of platforms presenting new films has made it harder than ever to keep up with everything happening in contemporary cinema, we asked some of our filmmaking friends to help us unbury a few of these neglected treasures, films they felt got lost in the shuffle. Ranging from releases that came and went in theaters to ones

that just deserve a closer look, their selections promise some great

alternative viewing as we hurtle toward 2020.

Ari Aster: The Homesman

How did the most deeply affecting western since Unforgiven go all but unnoticed—and how does it still remain unacknowledged? The release of Tommy Lee Jones’s second directorial triumph should have been noted as an event (at least a minor one!) after his directorial debut, The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada, which featured his finest performance (extremely steep competition there) and proved that he had a rare, intimidating command of the genre. Instead, the film’s tonal adventurousness was dismissed as unevenness, its deliberate and even visionary strangeness was regarded as the product of a director reaching too far (God forbid), and its middling reception almost convinced me to stay home. I’m so glad that I didn’t. The Homesman is a consistently surprising and often shockingly transgressive tragicomedy that doubles as a singular contribution to the western as well as a deranged (and deeply sad) essay on it. Also, it has an extended, blackly comic, narratively “wrong,” but thematically essential tangent near the end (with James Spader) whose resolution will keep me laughing until the end of my days.

Sean Baker: Paradise: Faith

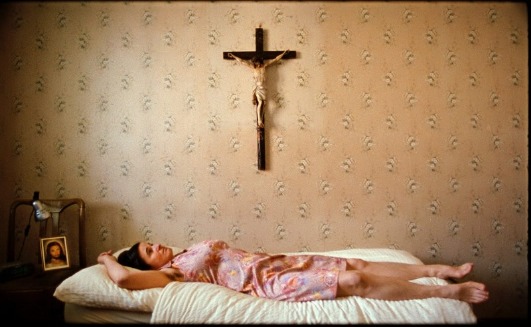

The second installment of Ulrich Seidl’s Paradise Trilogy is a film that I feel deserves to be recognized as an important, singular work. Maria Hofstätter gives a performance that feels so authentic and lived-in that if I hadn’t known her other work, I’d assume Seidl cast an actual fanatically devout Catholic in the role. Every shot is beautifully realized, by cinematographers Wolfgang Thaler and Ed Lachman, and justifies the slower pace in cutting, which lets us soak in the exquisitely controlled images. Seidl has a true command of his craft, presenting us with a satisfying twist and building to an oddly cathartic last shot, a bold conclusion that only Seidl and his writing/producing partner Veronika Franz could come up with.

Anna Biller: The Bad Batch

Many critics dismissed Ana Lily Amirpour’s The Bad Batch as empty pastiche, but for me it felt honest and original. It’s a movie that only works if you approach it with innocence and try to put yourself in the shoes of the titular group of characters, who have been discarded by society and left to fend for themselves in a dystopian setting. Upon finding herself there, Arlen (a dynamic and convincing Suki Waterhouse) is soon kidnapped and has her arm and leg sawed off by cannibals before managing to escape to a town called Comfort, where she is given the Hobson’s choice of living as the leader’s concubine and bearing his children. She again escapes and carves out her own world.

This is a self-assured and beautiful film, and it works at sustaining feelings of disenfranchisement and despair in a way similar to Italian neorealist films or the grimmest noir. In that sense it’s very classical, but its modern touches—the “rave” at Comfort, the homeless people, the drugs, etc.—are what plant it firmly in the world of young people today who live in social, cultural, and economic wastelands. It touches on great themes and is stylish and cinematic, but it’s also very personal and rich with black humor. I think it’s a masterpiece and that it’s only a matter of time before it’s reevaluated and placed in the canon of great films of our time.

Leslie Harris: Made in Bangladesh

Made in Bangladesh reflects on some of this decade’s major problems: global exploitation of workers, sexual harassment in the workplace, corporate greed. It also has a universal theme: how women during this decade gathered strength and courage to challenge oppressive systems and fight back. The protagonist, Shimu, runs away from home as a child after her mother threatens to marry her off, and escapes to Dhaka. After a friend and coworker dies in a fire at a textile factory where Shimu works, she embarks on a painful journey to make her world a better place. Writer-director Rubaiyat Hossain uses beautiful cinematic camera movement to capture Dhaka’s rich colors, vibrant textures, and raw deprivations. We watch women travel through poverty-ridden alleyways and backstreets to their paltry-paying jobs sewing T-shirts at the factory. Factory bosses intimidate, sexually harass, and exploit the women all in the name of profits.

The storytelling in the film is like the lead character—quiet, methodical, and tenacious, reminiscent of the great director Satyajit Ray. Shimu struggles to find her voice and becomes a union organizer fighting for women’s rights, safe factory conditions, and improved wages. This is a story of women’s solidarity, friendship, and fears, as they encourage each other to let their voices be heard. It’s a film that captures this decade of women’s empowerment.

Greg Mottola: Private Life

Though very well-received by critics, I still felt this movie deserved more praise and viewers. The subject, fertility, is a hard one for many people, but the film is really a portrait of a marriage being tested—and as such it rang deeply true to me. The writer-director, Tamara Jenkins, loves and knows her characters and never betrays them with sentimental pandering—they’re profoundly human, and we recognize ourselves in their quarrels, frustrations, and tenderness. And—no small thing for me—I probably laughed more during this film than I have during most straight comedies. I also loved the “unresolved” ending: the overt problem of the plot hasn’t necessarily been solved, but existential truths have been brought into sharp relief. Tamara has always tackled hard subjects as vehicles for examining the unpredictable course of love, and this movie is as wonderful as her others.

Alex Ross Perry: Hard to Be a God

The number-one film of the decade for me, without question and with no close competition, is Aleksei German’s Hard to Be a God. The fact that I have yet to see this film appear on a single best-of-the-decade list is inexplicable to the extent that I have to assume people just don’t know about it. If they did, it is inconceivable to me that anybody could adequately argue it is anything less than the most towering achievement of cinema we have seen not just this decade but this century. It may turn out to be the last true film, the final relic of the medium not as it exists today but as it was in the age of Tarkovsky, Kurosawa, Welles, and Bergman. The first time I saw it, my jaw hung open the entire time. There are shots in this film that, despite subsequent analysis, are impossible for me to understand the physical engineering of. It is one of a kind, the last of a kind, and no hyperbole can do it justice. We are richer for having it.

Daniel Schmidt: Various works

It’s difficult to choose a single work, owing to the unprecedented deluge of movies made this decade. Surely many are unappreciated simply because they proved difficult to find in a theater—and even more difficult to see projected multiple times. I was fortunate to be able to enter the theatrical world of Benjamin Crotty’s Fort Buchanan (2014) on several occasions. An ensemble and episodic film in miniature, it convenes, dissolves, and then reaffirms a small community to conjure a wholly unique cinematic sensibility and humor. Serialized over four seasons, it’s more affecting with each successive cycle.

Installed films—like those by bona fide art star and intuitive genius Rachel Rose: A Minute Ago (2014) and Everything and More (2015)—also lend themselves to revisiting, always affording some new iridescent glimpse of their fluid form, which is somewhere between sensation and investigation. Yet they remain largely concealed from the moviegoing public, captive to the art market’s calculated artificial scarcity, which strives to alchemize digital files into rarified objects.

Many reboots, sequels, and the like that were emblematic of the decade seemed to at once nullify the need for their precursors and even themselves—and were often critically dismissed. Yet some, like Jurassic World (2015), offered bewilderingly captivating dimensionality to their franchises. Perhaps unwittingly—it spared no expense in erecting a lavish satirical self-portrait—this film reanimates CG flesh to express the machinations of the entertainment economy with frightening beauty and clarity.

Twin Peaks (2017), while widely celebrated by many cinephilic communities, remains relatively unseen for a work of such vision and generosity. It is inexhaustible: infinite humanity, curiosity, wonder, and terror. Hopefully before another twenty-five years passes, it will become part of the core curriculum of high schools across this country.

Susan Seidelman: Ingrid Goes West

Matt Spicer’s quirky dark comedy Ingrid Goes West was released in the summer of 2017, and despite winning the Waldo Salt Screenwriting Award at Sundance, it quickly came and went in movie theaters. It deserves more attention, particularly due to the amazing lead performance by Aubrey Plaza.

Plaza plays the title character, a narcissistic sociopath who becomes obsessed with a beautiful social media “influencer” (played by Elizabeth Olsen) who appears to have the perfectly curated lifestyle. Ingrid, who is socially isolated and craves validation, confuses online likes with real human friendship and soon begins to emulate and stalk the object of her obsession. Plaza’s no-holds-barred performance is at times uncomfortable to watch. It takes you right to the edge of squirming. But it’s grounded in a distorted truth that makes the character fascinating, disturbing, and vulnerable.

The film is a razor-sharp portrait of today’s social-media-obsessed culture, where likes and cutesy emojis have replaced genuine human emotions. The story goes a bit off-track toward the end, when the violence threatens to overwhelm its satiric observations, but it’s still an underappreciated film well worth watching.

I admit I’m a sucker for movies about women who are obsessed with—or aspire to be—other women. Although Ingrid is a specifically millennial variation on that theme, it falls into a category with some of my favorite older movies, such as Single White Female, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, All About Eve, and Notes on a Scandal. And there’s no denying this theme’s influence on my own Desperately Seeking Susan.

Julie Taymor: Capernaum

For me this film was a revelation. I loved many things about it, from the idea of a child suing his parents for bringing him into this rotten world to the way it was made. It’s an extraordinary feat to blend a documentary feel with a thoroughly fictional storyline. This mix of a powerful and unique narrative with nonprofessionals who have experienced the raw emotions of the world being depicted is something I have never seen before. Like no other movie I know, Capernaum let me into a culture I knew nothing about, in a personal and dramatic way. The cinematography and music were also brilliantly employed. The passion for the subject matter and the idealism behind the way the movie was made shows in every frame.