James Baldwin and the Movies

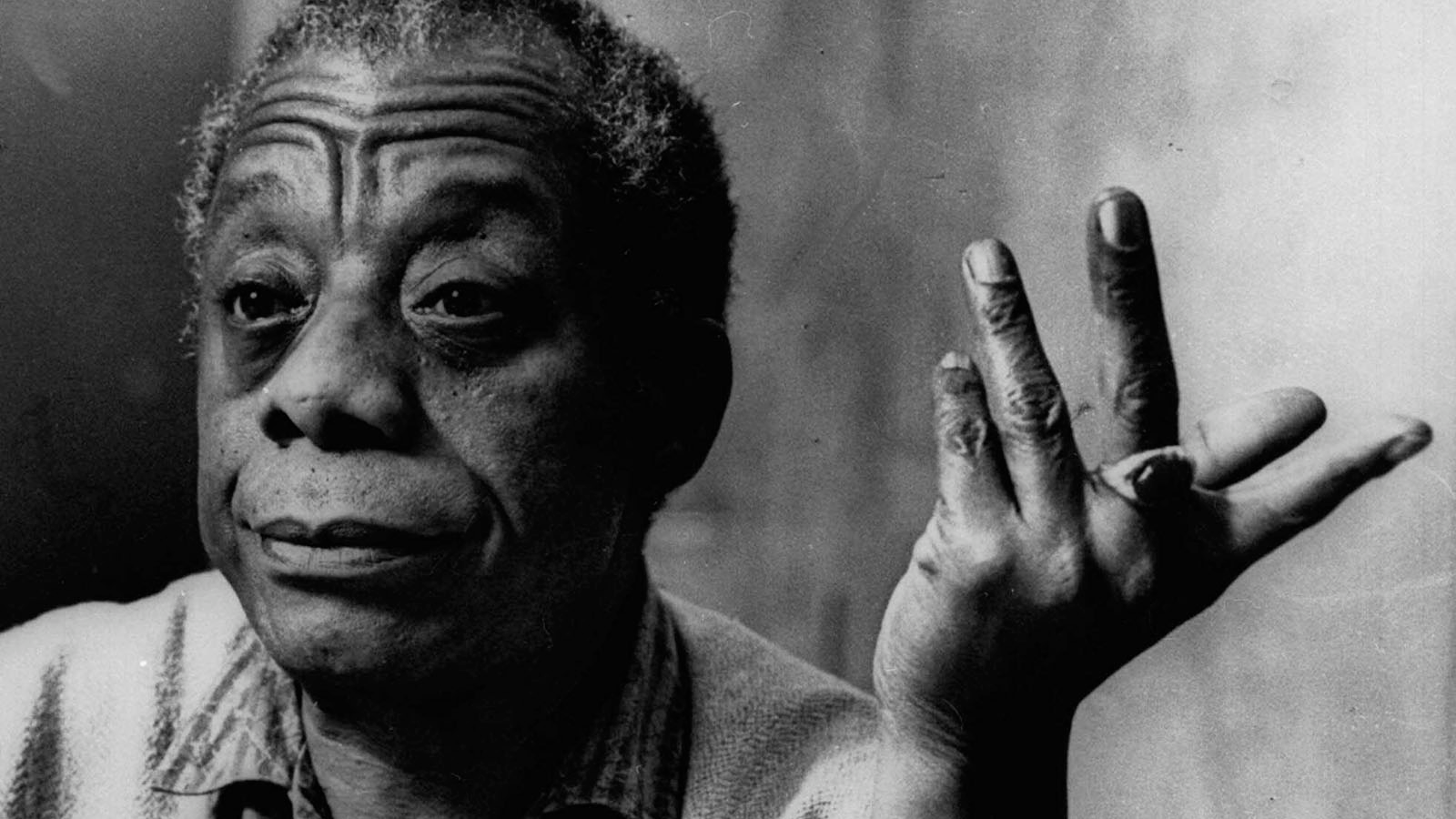

James Baldwin was not only one of the most vital writers and activists of the twentieth century, he was also a card-carrying cinephile. In a 2014 piece for the Atlantic, Noah Berlatsky went so far as to argue that Baldwin was the “greatest film critic ever” and that his 1976 book-length essay The Devil Finds Work, a “critique of the racial politics of American (and European) film,” is “one of the most powerful examples ever of how writing about art can, itself, be art.” More than a few filmmakers have found Baldwin to be an irresistible subject, and on Friday and Saturday, Hilton Als, a staff writer and critic at the New Yorker, will present three programs of films and video featuring Baldwin at New York’s Metrograph. The mini-series accompanies the group exhibition that Als has curated, God Made My Face: A Collective Portrait of James Baldwin, currently on view at David Zwirner Gallery through February 16. Reviewing the show for the Art Newspaper, Linda Yablonsky finds that it’s Baldwin’s “legacy as a gay man and a sexualized, social being that emerges from the biographical narrative unwinding here.”

Given how deeply Baldwin was engaged with the movies—Sheila O’Malley has posted a moving excerpt from The Devil Finds Work in which Baldwin writes about identifying with Bette Davis—it’s surprising that so few of his novels and plays have been adapted for the screen. A eulogy taken from his 1962 novel Another Country was the basis for just one half of an episode of the Canadian television series Quest in 1963, and in 1985, PBS broadcast an adaptation of Baldwin’s first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953), as an American Playhouse presentation. It wasn’t until 1998, more than a decade after Baldwin’s death, that a feature film was based on one of his works. French director Robert Guédiguian chose what Baldwin himself deemed to be the “strangest novel” he’d ever written, If Beale Street Could Talk (1974), as the source material for À la place du coeur (Where the Heart Is). Barry Jenkins’s version, then, is the first English-language feature adaptation.

The film is a realization of a dream that Baldwin had long harbored. In a New York Times Magazine profile, Jenkins shows writer Angela Flournoy a notebook in which Baldwin had written a few ideas for a potential adaptation. He could imagine Gordon Parks or François Truffaut directing it and would love to have seen Ruby Dee in the cast, perhaps as the mother of Tish, the young pregnant woman whose fiancé Fonny has landed behind bars after being falsely accused of rape. Writing for Slate, Kinohi Nishikawa argues that Jenkins’s film “manages to convey the strangeness at the heart of the book: a romance that turns on social outrage, a family drama that’s also a searing protest against the carceral state.”

Melanie Walsh, who’s been mapping the rise of interest in Baldwin on social media in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement and the release of Raoul Peck’s 2016 documentary portrait of Baldwin, I Am Not Your Negro, suggests in a piece for the Los Angeles Review of Books that, while “still tragic, the film is softer, warmer, more joyous, and, in many ways, less troubling than Baldwin’s original text. There are moments of grotesque horror, biblical terror, and everyday bleakness in Baldwin’s novel that the film’s congenial style cannot access and doesn’t try to.” At 4Columns, Andrew Chan notes that Jenkins’s version “replicates the fragmentary, non-chronological structure of the novel, but it also gives individual sequences the room to sing with a deeper resonance.” And not without losing the bite of the original text. The New Yorker’s Richard Brody sees the movie thrusting “the past and the present into the same plane of thought and evokes, above all, the politics of memory—the sense that memory is constitutive of history, of the history that may not be written but is nonetheless ferociously at work in the lives of people who are themselves largely left out of the official record.”

Writing for Esquire last fall, Jenkins recalls that he first discovered Baldwin’s work “when my no-longer girlfriend looked at me squarely and said, ‘You need to read James Baldwin.’” So he read Giovanni’s Room (1956) and The Fire Next Time (1963), and “from the very moment I finished those books, I dreamed of translating Baldwin’s prose into imagery.” He ultimately chose Beale Street “because I felt the novel, more than any of his other works, represented the perfect blend of Baldwin’s dual obsessions with romance and social critique, as sensual a depiction of love as it is a biting observation of systemic injustice.”

For news and items of interest throughout the day, every day, follow @CriterionDaily.