Lars von Trier’s Europe Trilogy: Straight to the Bottom of the River

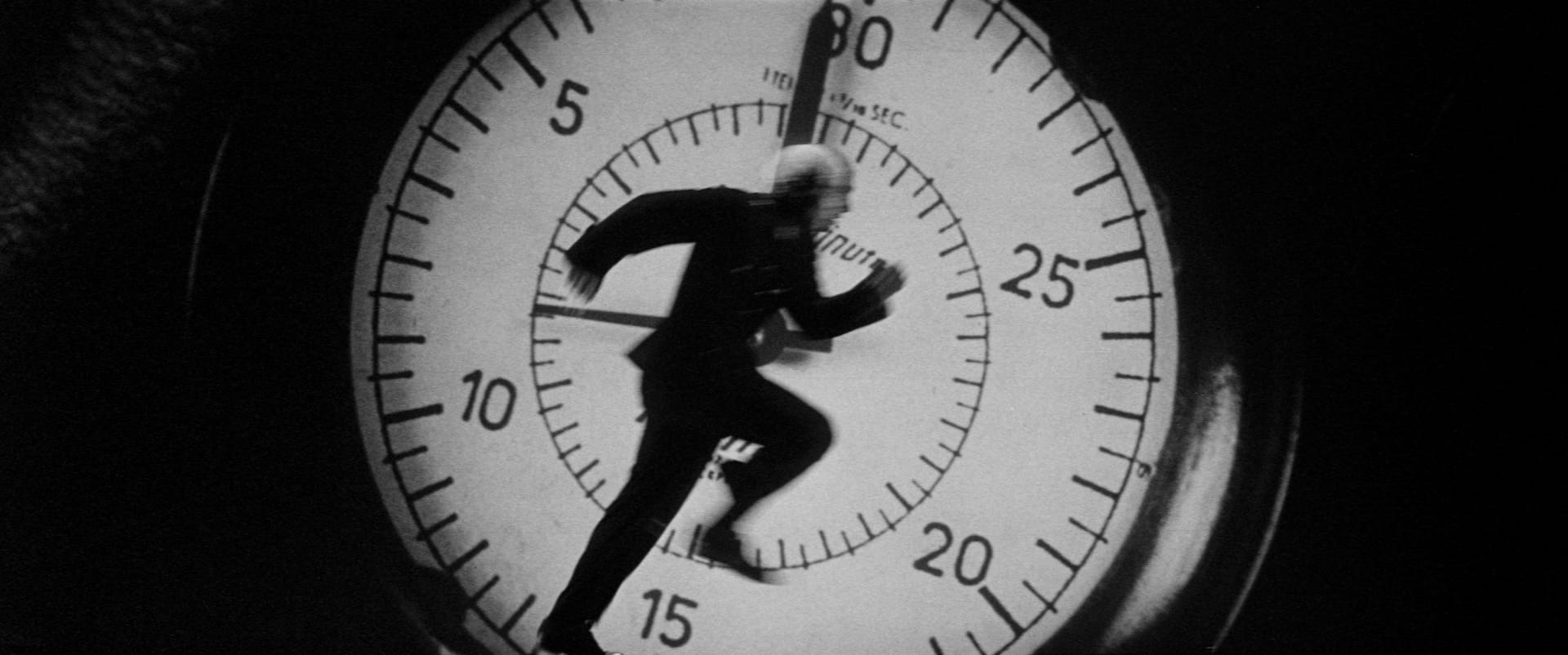

Cinema is an illusion. That’s the motto I’d nail over the entrance to Lars von Trier’s Europe Trilogy, the three cage-rattling films—The Element of Crime (1984), Epidemic (1987), and Europa (1991)—with which the director launched his brilliant, maddening career as an aeonian enfant terrible. These movies were conceived as a triptych, linked formally by their hypnotic slipperiness and satirically by von Trier’s conception of a postwar Europe still in unconscious thrall to the demons and ghosts of fascism. Doubling down on the full primitive-to-sophisticated cinematic spectrum of magic, lies, wishful thinking/ideology/religion, personal fetish/fantasy, and literal-cum-metaphorical projection, they push the illusory nature of film to its breaking point. With their blend of high-art severity, bold pop strokes, parodic-ritualistic iconography, and self-conscious amusement bordering on sociopathy, they are “thrillers” that eviscerate Eurocentric and Hollywood traditions with fantastic sleight-of-hand brio.

Pauline Kael famously titled a 1963 piece on alienation-chic movies “The Come-Dressed-as-the-Sick-Soul-of-Europe Parties,” a phrase nicely suggestive of the Europe Trilogy’s ambience. One difference between von Trier’s cycle and, say, Last Year at Marienbad is its built-in mockery: these movies are ebulliently mortifying. Autopsies conducted with showmanship, they aren’t morality plays or studies in oblique decadence but phosphorescent grenades lodging their shrapnel within self-satisfied assumptions of art and meaning. In Epidemic, von Trier offers a simpler motto of his own: “A film ought to be like a pebble in your shoe.” Sometimes he makes it feel like he’s squeezing boulders of repulsion into size-eight loafers, but he doesn’t succumb to the entropy and rot he depicts. He floats above it like a charlatan savant (hypnotism figures prominently in all three movies), ransacking European and cinematic history with debonair impunity. He’s the nihilist as master thief. Treating the making of movie art as if it were a beautifully intricate long con, von Trier operates less like an antipolitical Bertolt Brecht than a cineaste Ricky Jay. He sets up all these fantastic alienation effects and lets us queasily savor the inner workings of obfuscation—the hard-boiled-detective swindle, the sickening horrorfest gimmick, the glamorized paranoia of the thriller’s moral misdirection.

Having navigated the rigidly parochial programs of the University of Copenhagen and the National Film School of Denmark, von Trier shot The Element of Crime, his chillingly overloaded shock corridor of a feature debut, in English. It would be hard to overstate what an affront the project was to the social-realism-favoring Danish system that financed him. The future director of sanguinely punishing, trauma-inflicting fare like The Idiots (1998), Dogville (2003), and Antichrist (2009) assumed a whole larger-than-Denmark persona, down to adding the aristocratic von (shades of von Stroheim, as in Erich, and von Sternberg, as in Josef). He egotistically (another Scandinavian no-no) aimed his work at a wider world—one from which he could cannibalize a banquet spread of celluloid appendages: Touch of Evil, Andrei Tarkovsky, Blade Runner, Fritz Lang, Sam Fuller, all the way down to the anachronistic message tubes from Brazil.

Crime is a “vision” of a Germany that never recovered from the Second World War, a half-submerged industrial landscape where nothing works anymore, and where everything the postwar economic miracle papered over is instead out in the open like a festering wound. The washed-up police detective Fisher (Michael Elphick), living in exile in Cairo (a suitably noir touch), undergoes hypnosis in order to recollect the case of a serial killer, transporting him to the wasteland of his lost memories. He encounters his old mentor Osborne (Esmond Knight), a criminologist who wrote the titular book on retracing a killer’s footsteps in order to meld with his warped mind. Hypocrisy is permeative; corruption is the weather (and it’s pouring). A blowhard chief inspector wields a bullhorn to amplify his fascist fatuousness. A prostitute (MeMe Lai) with secret links to the case arrives on schedule. Cultists enact rituals, drowned horses are the visible signs of a foot-and-mouth pestilence that’s going around, and the cop’s Volkswagen seems like a creature from a medieval lagoon.