Birago Diop was a brilliant high-school student in Senegal. During his final exam, he made the unusual mistake of misconjugating a French verb, an error that was to prove fateful for his career. With a wry, self-deprecating smile past the camera, Diop, now an acclaimed poet and short-story writer, declares that what happened to him followed “the law of destiny.” The professional paths open to colonial students in the French system were narrow: they could become teachers if they passed a critical test, or doctors or civil servants if they didn’t. Diop went on to study veterinary medicine in France, and his collections are filled with animal tales.

Sitting behind the camera and listening to this story in Birago Diop, conteur (1981), Paulin Soumanou Vieyra, the Beninese-Senegalese filmmaker, historian, critic, and bureaucrat, must have heard something of his own travails. The two men, both outstanding artists, achieved renown despite the constricting educational system of the French colonies. As African American writer James Baldwin once pointed out with regard to Aimé Césaire, the Martinican poet of Négritude, colonialism was responsible for creating the same intellectuals who would undermine it. Vieyra, in fact, ran a greater risk of assimilation than Diop.

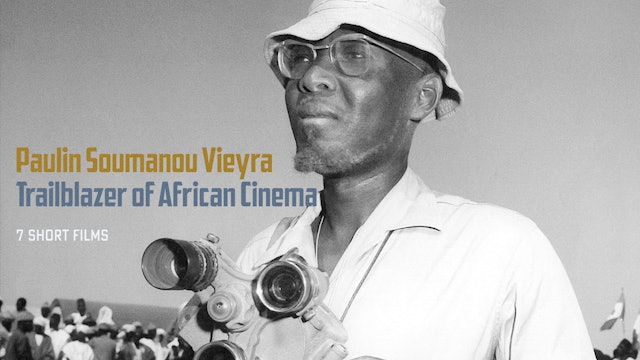

Born in 1925 in Porto-Novo, Benin, he was ten when his parents sent him to France to study. He did not return home until the age of twenty-five, when he fell ill with tuberculosis. Back in France in the early 1950s, he underwent an operation on his lungs. There are conflicting stories about his reasons, but Vieyra switched from his chosen academic field and wound up enrolling instead in the famous Institut des Hautes Études Cinématographiques (IDHEC). According to his son Stéphane, Vieyra had had an early experience with cinema, as an extra in Claude Autant-Lara’s Devil in the Flesh (1947), and recalled as unforgettable the moment when Gérard Philipe was called to step onto the set. As fate would have it, Vieyra’s time at IDHEC made him not only the first African student to enroll in the school, but also among the first to make a film about the African experience in Europe.

That film, Africa on the Seine (1955), stands at the beginning of African cinema, though it was not filmed on the continent. At that point, the Laval Decree of 1936 still required that filmmakers obtain the French government’s permission to shoot or screen films in the colonies, and effectively banned colonized people from filming themselves. Despite being made under that censorship regime, Africa on the Seine is an eloquent, luxuriant feast of cultural self-affirmation. Produced collectively with the African Cinema Group in Paris, the twenty-two-minute film depicts the sociocultural complexity of France, particularly its capital, in relation to the identity of its Black residents. The narrative arc begins in an unspecified African location, with footage of village children adapted from René Vautier’s Afrique 50 (1950), and then arrives at Paris’s Left Bank, as seen from a mature perspective expressed in a first-person-plural voice-over. Paris may be the “capital of the Black world,” but it is also the capital of France, the country where “machine noises [have replaced] those of men of nature,” barely out of the first Indochina war, but preparing for another campaign in Algeria. The attendant discomfort echoes Césaire’s Notebook of a Return to My Native Land, and would resonate in the work of later-generation African directors such as Jean-Marie Teno (Africa, I Will Fleece You, 1992) and Abderrahmane Sissako (Life on Earth, 1998), in centering individual subjectivity against the onslaught of a powerful political system.

The voice-over is poetry modulated by thought. This voice is a “we” rather than an “I,” a collective identity that reflects the way the film was made. There is something of the classic predicament of the colonial intellectual in this voice, the voice of a poet whose people has not been born, at once exploring a personal outlook and calling forth a community that is far from stable. This ambivalence conveys a complex African subjectivity, at a time when colonial portrayal of the continent’s diverse cultures ran through a narrow set of stereotypes.

In one beautifully edited sequence, the voice-over speaks of the streets of the Left Bank as the space of the discovery of “civilization, at the school of outstretched hands,” at the very moment when a white street beggar importunes a Black pedestrian for alms. This concordance of image and poetry is striking in the way it exposes the class dimensions of a culture that gives priority to racial divisions: Parisian streets are filled with many contradictions, visible only through an actual encounter with the metropole.

Vieyra’s relationship to his homeland was spotty. He could not recognize his own mother at their first reunion, after fifteen years in France, and he no longer spoke Yoruba, his first language. His return the second time around without a degree in a prestigious profession was unforgivable in Benin, a country that unironically prided itself on being the “Latin Quarter of Africa” thanks to its educated elites. He could not secure employment in his native country, and it took Senegal to come to his rescue. In 1956, Léopold Sédar Senghor, the Négritude poet soon to become the founding president, hired Vieyra to head Actualités Sénégalaises, a film institute that he would develop into a database of the cultural transformation of the emergent country. He also became the first director of the Senegalese Office for Radio, Broadcasting, and Television and the Science and Information Technology Research Center.

From these positions, until he resigned in 1975, Vieyra wrote, directed, and produced scores of films, and published criticism as well. At his death in 1987, his completed output included thirty films, five books of film history and criticism, and numerous articles and conference reports. He also produced most of the early films of the Senegalese director Ousmane Sembène and wrote the first detailed study of the filmmaker. In a short tribute published in 2004, Sembène wondered if he would have made any films without his “deep connections to Paulin Vieyra.”

It is a unique legacy, and for all the bureaucratic exactions, Vieyra succeeded in creating a cinema of his own. For a man whose great-grandfather had been deported as a slave to Brazil, and whose father was a Yoruba in Benin, Vieyra’s legal and professional standing as a Senegalese man of culture illustrates the turbulent nature of identities in African life. In just three generations, a family’s trajectory could encompass different worlds, thus giving the lie to the stereotype of an unchanging, culturally backward continent. This is reflected in his films, noted for a clever matching of style and subject.

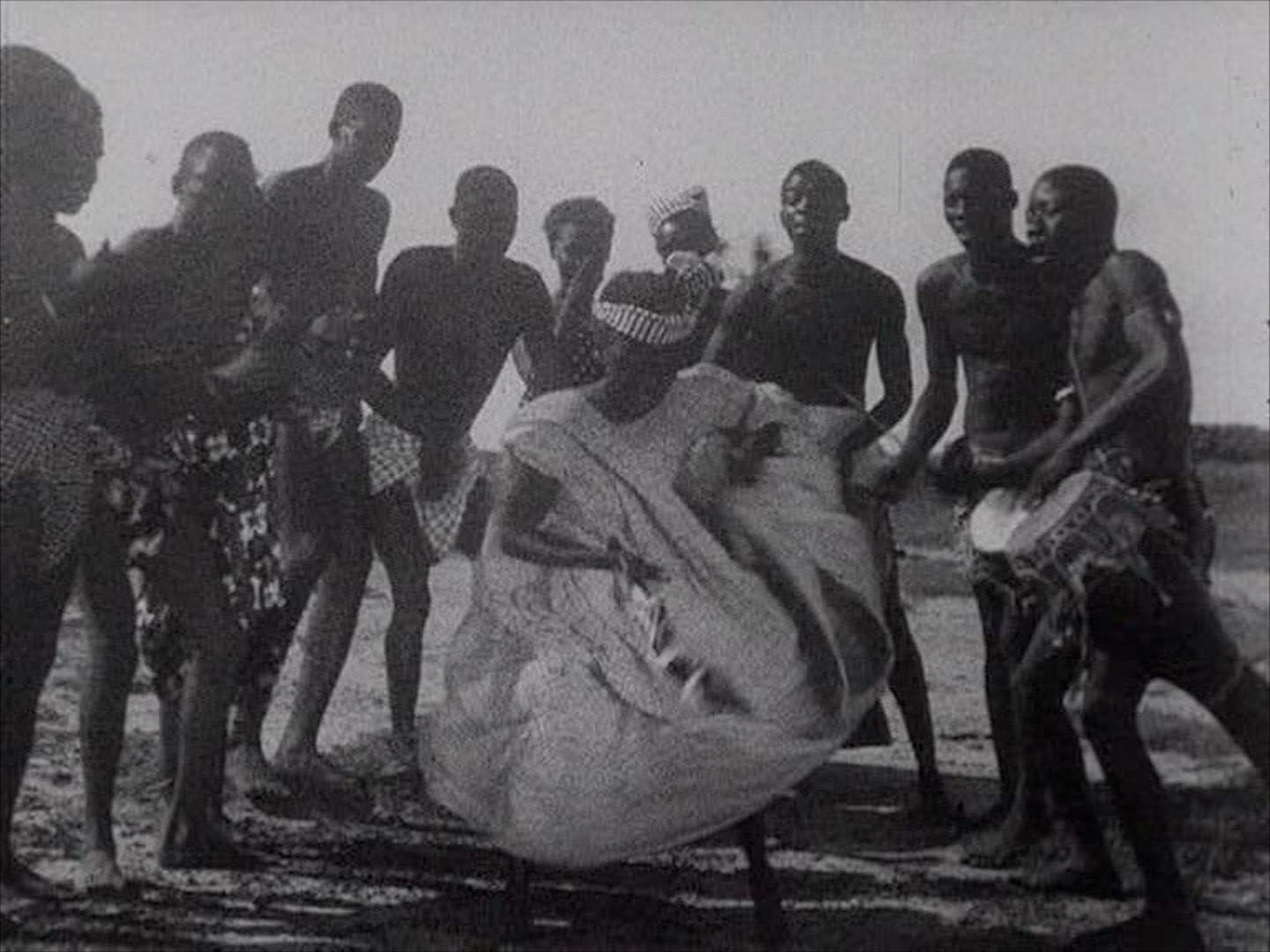

Released in 1961 and narrated in the theatrical cadences of Bachir Touré’s voice, A Nation Is Born stands high among the best African ethnographic films. In fact, it has the edge on some (Jean Rouch’s, for example) in showing a remarkable variety of activities and differentiations within a single country. It is not simply official newsreel, or colonial ethnography, but the dynamic marriage of the needs of a public-spirited government to the technical capacity of a self-assured filmmaker. There are long sequences from the inauguration of Senghor’s presidency, and texts extracted from his poetry and the Senegalese national anthem. The country’s physical geography becomes a narrative template for reconstructing a history that plays out in the discrete moments of work—by fishermen, women, and various artisans—that we glimpse, along with children competing at dance.

If high patriotism and the long historical sequence supply the mise-en-scène in A Nation Is Born, the pace and the sound of Lamb (1963) are fully in the realm of the everyday. It is Vieyra’s first color film, a record of wrestling as a national sport celebrated much like a public holiday. The festive occasion gathers many participants—spectators, law enforcers, vendors, gamblers, miscreants—creating a fertile ground for capturing the essence of community on film. Lines from “Souffles” (Breath), a poem by Diop, signal the arrival of the unseen spirits behind the contests, and as the combatants flex, hedge, and wait, the voice-over changes registers. “Gestures are sublimations,” we hear, “in which men find their essence.” People from all walks of Senegalese life are out in full force. Those who do not go to the stadium sit next to their radios, listening. The contests are broadcast live, and in two brief moments Sembène is seen listening, then jubilant as his favored wrestler wins.

Vieyra learned filmmaking by the book at IDHEC: cinema as classical montage, a learned style of engendering meaning through the realistic manipulation of image and sound, with editing as the decisive technical element in this artificial process. Speaking in 1978, Vieyra sounded dubious about that academic approach, observing that “those who studied at IDHEC . . . received an education that has stalled them in their creative impulses.” Yet he found a balance between those textbook ideas of filming, an artist’s creative hunches, and the hit-or-miss impulses that appeared in the field, in part because he had full-time employment and was able to work constantly. Theoretical ideas did not always hold up well in production, as Sembène notes plaintively in Vieyra’s documentary Behind the Scenes: The Making of “Ceddo,” observing that they couldn’t review their work in progress since the dailies had to be sent to Paris for processing.

In all of Vieyra’s major films, the soundtrack is an integral aspect of the storytelling: evocative, sensuous, and capable of orienting a given narrative in a direction that may not be clear from its visual aspects. Halfway into Africa on the Seine, the pace slows down for a two-minute sequence of pure whistling and guitar, remarkable for leading to the appearance of a young woman waiting, smiling at the camera. She is Marpessa Dawn, later the star of Marcel Camus’s Black Orpheus. Similarly, in Môl (1966), about the efforts of a young fisherman adapting to changing technology, there is a ninety-second sequence of near-total silence, with rowing and environmental noises coming to the fore of the soundtrack. This is when the fishermen are out at sea, and the drudgery, if that, is sublimated into the gestures of work. The wrestling sequences in Lamb provide another good example. The combats unfold in multiple places—on sand, on grass—that are linked by montage to the spectators’ stands. However, the viewer is made to enjoy them as a single event through cuts that create a near-seamless progression of activities. The film’s single soundtrack is sustained throughout, without modulation or change, reinforcing the focus that drives the sport.

Perhaps the most extraordinary twist in Vieyra’s destiny is the fact that, though sent from home to school at age ten, and to a society as self-assured as France, he grew into a confidently Africa-centered intellectual. His job in Senegal might have had something to do with his success in weaning himself off Eurocentric affectations, if he had any, because he was in the service of a government that had set itself the mission of creating a new African culture. His attitude is reflected in Iba N’Diaye (1983), a portrait of the eponymous Senegalese artist, a modernist from a social background similar to Vieyra’s own, and the first director of Senegal’s National Fine Arts Academy. N’Diaye comes across as reverential of European masters, but he clearly sets his priorities on depicting African realities.

The questions that preoccupied pioneers of African filmmaking such as Vieyra and his close collaborators revolved around how to express the complexities of the continent’s cultures without denying the personal dimensions of their French education. Tunisian director Férid Boughedir captured this dilemma when he said that African cinema exists because and in spite of France. Sembène resolved the issue by refusing to prioritize European perspectives or needs, while also developing a Marxist critique of postindependence politics. The question of language was key for him as well: cinema enabled him to reach a nonreading public, and beginning with Mandabi he moved away from French in favor of noncolonial languages.

By the time Vieyra settled into his various roles in Senegal, the Laval Decree was a dead letter, and the orientation of his work was decidedly African. He had misgivings about the impact of Africa on the Seine, arising mainly from the fact that it was codirected and did not represent a single vision. But the interest in cultural self-retrieval in that work stayed with him, becoming stronger as he found wider institutional and artistic horizons. He was just as sensitive as his peers to the question of representation, constantly worrying about how to get African films out, make African directors known, and provide cultural education to young filmmakers. It is likely that he took on writing and producing mostly to fill these needs. The variety of roles he played in the nascent film industry suited him for the conference circuit and the boardroom, the domains of brokering and deal-making, and certainly made him less combative than the mercurial Sembène. (Recent biographical details have shown even the latter to be a pragmatist in real life: “I would sleep with the devil in order to make my films,” he says in the documentary Sembene!) Vieyra did not speak another African language after losing his Yoruba, so French was all he had. Nonetheless, these limitations did not affect the clarity of his artistic vision, which was unquestionably African.

The insistence with which Vieyra poses questions to Birago Diop and Iba N’Diaye in his filmed portraits of them seems to reveal a process of self-questioning. Like him, these men were products of the French educational system, that is, prime candidates for cultural assimilation into French life. But they returned to the continent to undertake work—fiction, painting—that depict African realities from the inside.

Vieyra used cinema to a similar end. As he declared in his book on the cinema in Senegal, “I would like to offer, first and foremost, an African point of view.” As far back as 1975, he had made a case for the collective term “African cinema” to describe the continent’s emerging film tradition. His reason at the time was that the cinema industries in African countries were not strong enough on their own to withstand discrete treatments. The term has remained timeless and serviceable, and reinforces a vision of cultural solidarity that most people now take for granted. In his compositional style, his approach to a variety of subjects through an easy mix of the investigative and the declarative, and his resourceful use of montage, he clearly inaugurated a directorial approach that other African filmmakers have appropriated. As Vieyra’s films, now restored and available to stream, become increasingly visible, the scholarship on African cinema will be richer and more sophisticated.

All images courtesy PSV Films

More: Features

Thoughts Transcending Time and Distance: Makoto Shinkai’s Voices of a Distant Star

In this early-career gem from one of the most beloved Japanese animation directors of all time, an extravagant sci-fi narrative is anchored by the transcendent power of young love and poignant observations of modern life.

Trash and Treasure at the Razzies

What makes a “bad” movie anyway? By surveying the bombs, disasters, and secret masterpieces (dis)honored at the Golden Raspberry Awards, we can learn much about American cinema’s prevailing standards of taste.

Cinema Revolutionary: Fernando de Fuentes in Morelia

The subject of a revelatory retrospective at last year’s Morelia International Film Festival, this groundbreaking director ushered in Mexican cinema’s golden age with vibrant explorations of the nation’s folk traditions and revolutionary past.

Becoming Hou Hsiao-hsien

Though the Taiwanese director began working in commercial genres, even his earliest mainstream films contain the seeds of the inimitable style that would establish him as one of the world’s most important filmmakers.