Kazuo Hara’s Dedicated Lives

The notoriety of The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On (1987) always precedes it, yet the film never fails to evoke shock and wonder at its stunning improbability. The subject of this documentary is one of cinema’s greatest bullies. Both relentless and charismatic, Kenzo Okazaki was a veteran of the terrifying battles on Papua New Guinea at the end of World War II, and was clearly damaged by the experience. At the time of shooting, the radicality of the war’s violence was being erased from history by Japan’s right wing, and Okazaki was on a mission to push his audiences’ noses into the messiness. He tyrannically usurps the filmmakers, positioning them as mere witnesses to his project: visiting his old army buddies one by one to literally beat the truth out of them. Having witnessed or participated in crimes perpetrated against Japanese soldiers by their own officers, these men have a secret, and its revelation and memorialization on film is Okazaki’s mission.

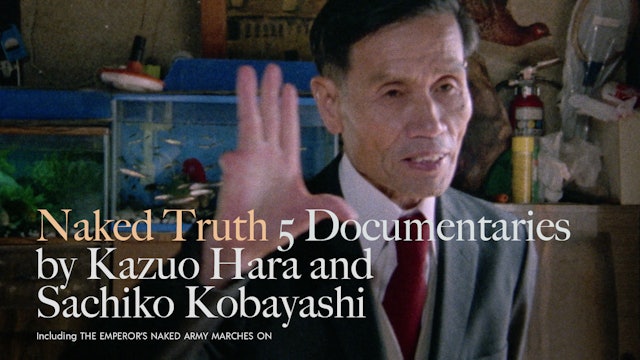

This is one of those films that people always remember where, when, and how they watched. It made the career of its director, Kazuo Hara. To this day, anyone introducing him inevitably invokes Emperor’s Naked Army, even though his entire filmography makes for compelling viewing. With five of his films, made over a span of more than four decades, now streaming on the Criterion Channel, it’s worth examining the arc of his career and his pivotal place within Japanese cinema’s vibrant documentary tradition.

For me there are two Kazuo Haras, Hara 1 and Hara 2. They have a supplemental relationship—one is unthinkable without the other. One is always already secreted inside the other. Interestingly, Hara 1 and 2 map out against two filmmakers who deeply impacted Hara’s thinking about the world and cinema. In a recent interview about Sennan Asbestos Disaster (2017) conducted by Joel Neville Anderson, Hara explained,

My personal view is formed by the views of two people, one of them being Shohei Imamura, who said that films should depict people. And what he means by that is, people are cowardly, they’re lecherous, they’re cheap, they’re immoral—and that’s what makes them interesting. When you depict people, those are the aspects that you should depict, because it makes them more human. The other person is . . . Kirio Urayama, and he said that film is for the people. It’s for the proletariat, for the weak, the downtrodden. It’s not for the powerful. Many films exist as de facto PR film for the powerful, so those are not the kind of films that you should make. You should make films that try to make the lives of the downtrodden and the weak better, and bring happiness to them. Those two concepts basically formed my thinking of what film should be.

Hara’s reputation, particularly outside of Japan, is almost entirely built around his first several films: Goodbye CP (1972), Extreme Private Eros: Love Song 1974 (1974), Emperor’s Naked Army, and A Dedicated Life (1994). These are works that are profoundly inflected by Imamura’s earthy anthropology, or, as the older filmmaker famously put it, “the relationship of the lower part of the human body and the lower part of the social structure.” Each film pivots around the locus of a captivating individual’s body. And to one degree or another, each film involves a struggle over directorial control. In contrast to this, there is a second Hara who embeds himself—and the viewer by extension—in groups of regular folk, under duress and in need of support. To tease this history out and understand these two complementary sides of Hara, it helps to place him within the larger history of Japanese documentary.