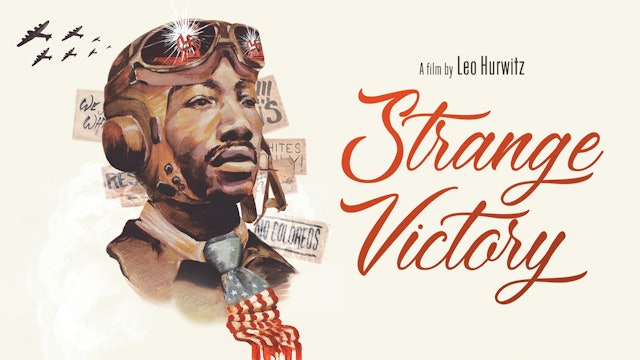

Antifascism on the Home Front

In 1948, leftist filmmaker Leo Hurwitz directed a documentary whose title summed up the uncertainty of its moment: for America’s antifascists, the end of the Second World War was a Strange Victory indeed. Using newsreels from the war’s front lines, footage shot in the U.S., and provocative narration and editing, Hurwitz’s film grasps the nettle of the tumultuous decade that was the 1940s by dissecting a cruel irony. The United States had expended copious amounts of blood and treasure to defeat fascism and its close comrade, unalloyed racism and bigotry, while fighting with a Jim Crow army, the inevitable result of an existing apartheid society. Victory can’t be complete, the film’s narrator observes, “with the ideas of the loser still active in the land of the winner.”

The radicalism of Strange Victory comes out of the Popular Front, an international movement that exercised a powerful influence on U.S. culture in the 1930s and ’40s. Initiated during the Great Depression and often led by the U.S. Communist Party, the Popular Front grouped under one umbrella radical and liberal forces animated by antifascism. Grounded in expansive labor-organizing campaigns, it fought against Jim Crow in the South, ran solidarity campaigns for international causes like Republican Spain, and lent grassroots support to the programs of the New Deal. At the peak of its strength, the Popular Front gave rise to a trend that did not outlast the end of World War II: Communists, liberals, and even some centrists acting in concert, especially on an antifascist, pro-labor, antiracist basis.

Though Strange Victory was an independent production, Popular Front politics had a clear impact on the mainstream as well, especially by the end of the war. Take, for example, “The House I Live In,” a composition by Communist songwriters Earl Robinson and Abel Meeropol, which asks, “What is America to me?” and answers, “The house I live in, / my neighbors white and Black / the people who just came here / or from generations back.” Before it went on to become a signature tune of Paul Robeson’s, Frank Sinatra sang it in an Oscar-winning short film of the same name released in 1945. The contemporaneous production of Gentleman’s Agreement was intended to undermine anti-Jewish fervor, and even the cinematic version of William Faulkner’s 1948 novel Intruder in the Dust issued a critique of anti-Black racism.

These films came about in the context of that brief “American Spring” when liberal and left movements and ideas seemed to be in the ascendancy—even in the White House, where Vice President Henry A. Wallace served alongside President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Of course, by 1944, Wallace was ousted from this lofty post, replaced by the centrist Democrat Harry S. Truman. By the time Strange Victory appeared in 1948, Wallace was the standard-bearer for the newly minted Progressive Party, one of the last serious efforts by a rapidly diminishing Popular Front to claim power. This decline was accompanied by a like-minded purge of the film industry, with the blacklisting of the Hollywood left.