Amores perros: Force of Impact

One day in the late

1990s, when I was a young staff member at an art and media magazine, my boss

asked me to interview an esteemed creative director of an ad agency. A few

months earlier, that same magazine had dedicated an issue to the newly

resurgent Mexican advertising industry and had asked a number of agencies to

help compile a list of the top creatives in the country. Strangely, the name of

the man I was tasked with interviewing, who had won prizes in the field, had

not been included on that list. One of my aims was to ask his opinion about

this omission.

His name was

Alejandro G. Iñárritu, and he was well known at the time for his innovative and

playful “stingers”—station-identification announcements—for Channel 5, one of

the many stations owned by Televisa, the largest television broadcasting

company in Latin America. However, those of us who lived in Mexico City were

more familiar with another side of Iñárritu. In the mideighties, he had been a

DJ at WFM, a radio station whose on-air personalities really tried to connect

with their listeners, breaking from the rigid, solemn format of so much FM

radio at the time (in 1988, he became the station’s music director). They were

chatty and often mischievous, and they were free to play whatever they liked.

Iñárritu had a daily show that was three hours long, on which he mixed all

kinds of music, from classical to rock to tropical beats. His powerful voice

was part of the soundscape of the city.

Despite Iñárritu’s

high profile, the assignment to interview him rubbed me the wrong way. As a

film critic who was just starting out, I didn’t want to write about

advertising; I wanted to speak with the best directors of my generation. Little

did I know that this man would soon be among them.

When I arrived for

the interview, I met a person of quiet demeanor who gave deliberate, unhurried

responses. I asked him about his omission from the list. He said it was because

he and his team did not follow industry protocol. They regarded commercial

assignments as opportunities to experiment with different filmmaking

techniques, and they generally did not hold meetings with clients in order to explain their approach to a given

project. He and his team prided themselves on being accountable to no one, and

that was often not appreciated by his peers in the field. Toward the end of our chat, Iñárritu told me that

he would eventually film a feature. He didn’t place a lot of emphasis on it,

though. And neither did I: I left that detail out of the interview that was

eventually published.

Three years later, on

June 13, 2000, 3,400 people attended the Mexican premiere of that feature at

the Teatro Metropólitan, one of the most famous cinemas in Mexico City. The

film, titled Amores perros, was about to alter the

course of Mexican cinema. That night, we knew only that it had been awarded the

Critics’ Week Grand Prize at Cannes—news that had generated enormous

expectations in Mexico, where audiences had been gradually turning away from

their national cinema ever since its so-called golden age had concluded at the

end of the fifties. In the decades that followed, the bureaucracy surrounding

Mexican filmmaking had grown, budgets had become limited, and the generally

lower-quality films that were made were often unable to compete with those from

other countries. Little of the cinema produced during this time reflected the

political and social changes that were occurring in a country whose moviegoing

public was increasingly eager to associate itself with what was modern.

It was amid murmurs

of anticipation, then, that those of us at the Amores perros

premiere took our seats. Finally, the lights went down and the screening began.

As I watched the opening sequence, I couldn’t help but remember how casually

Iñárritu had mentioned his desire to eventually direct a feature. This was

definitely not the work of someone who was just trying his luck. The action

kicks off at a furious pace: A car speeds down city streets, the driver’s eyes

riveted to the rearview mirror. A pickup truck is on his tail, and inside it a

man takes aim with a pistol. While he dodges other vehicles, the driver of the

car asks the passenger sitting next to him if the wounded rottweiler in the

back seat is still alive. As the pickup catches up, the driver of the car steps

on the gas, running a red light—and colliding suddenly with a white car

crossing the intersection. The driver of the white car is trapped inside,

pleading for help. The fate of the driver who caused the crash, his car’s hood

now severely damaged, is unclear.

By this time, Mexican

audiences had seen plenty of car-chase films from other countries. And Mexican

cinema boasted its own stunt tradition, in which showy crashes and cars falling

off cliffs were frequent sights. From that perspective, Amores

perros’s opening chase scene was nothing unique. But right away on that

night at the Teatro Metropólitan, we intuited that we were not seeing just

another movie—a sense that was confirmed as the accident was revealed to be a

hinge connecting three stories. If the opening is an electrifying assault on

the senses, the structure of the story, conceived by Iñárritu and screenwriter

Guillermo Arriaga, presents viewers with a mysterious and thought-provoking

juxtaposition of events. Each section of the film bears the name of an unhappy

pair. In “Octavio y Susana,” a young man from a slum (Gael García Bernal) falls

in love with his sister-in-law (Vanessa Bauche); in “Daniel y Valeria,” a

married fashion editor (Álvaro Guerrero) buys an apartment for his model

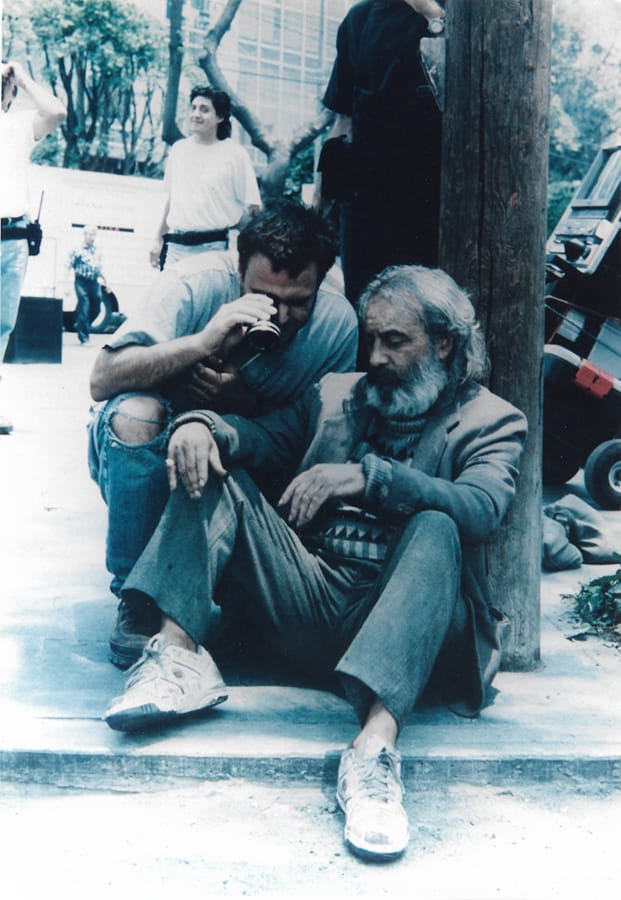

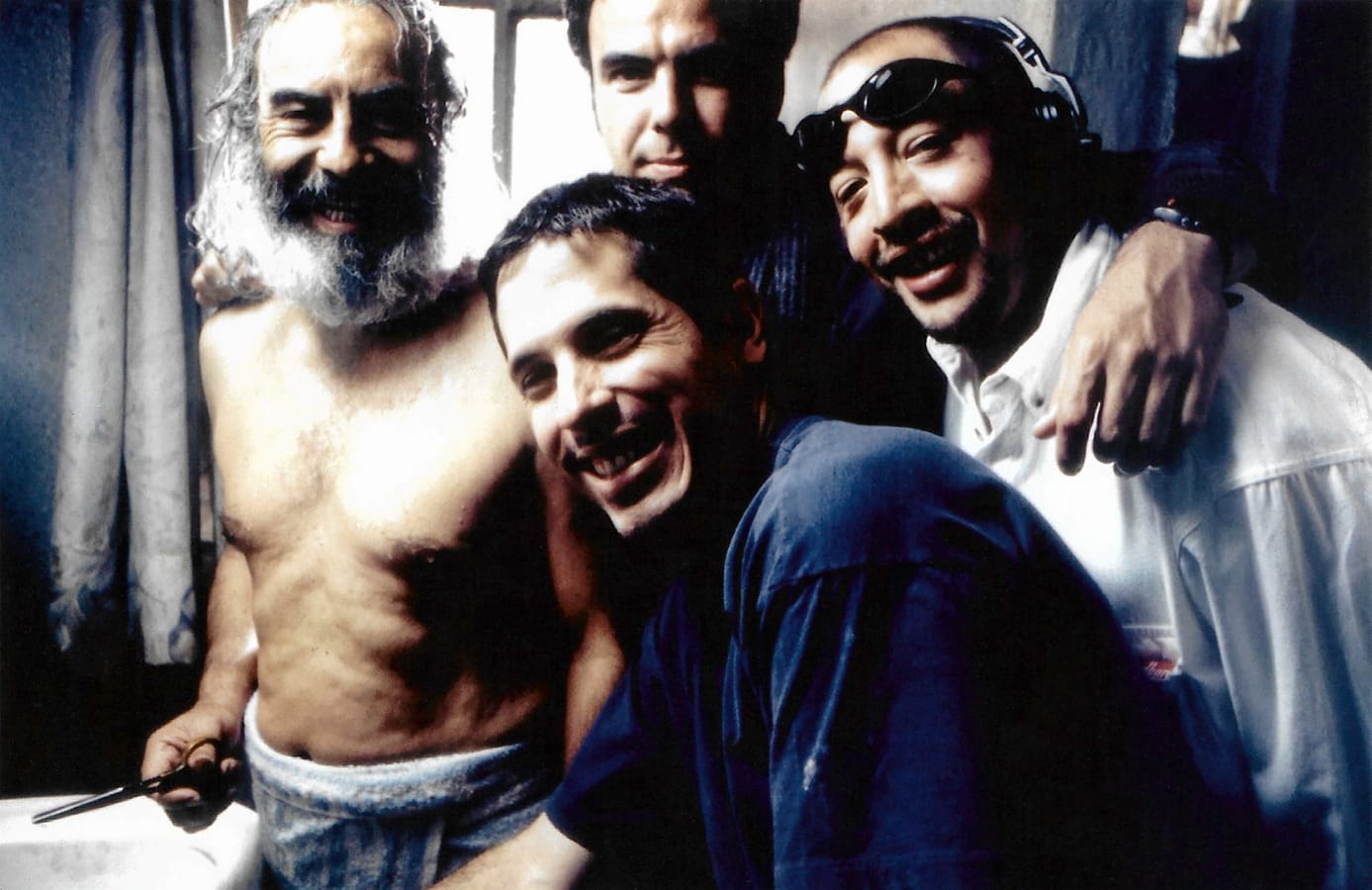

girlfriend (Goya Toledo); and in “El Chivo y Maru,” a guerrilla turned hit

man (Emilio Echevarría) seeks the forgiveness of his estranged daughter

(Lourdes Echevarría). The drivers involved in the car accident turn out to be

Octavio and Valeria, and later we see El Chivo rescuing Octavio’s rottweiler

from the scene. The crash is a metaphor for the collision of the vastly

different socioeconomic universes that all occupy the same streets in Mexico.

In Spanish, the

phrase amores perros refers to relationships that are

cursed, impossible, and foolish. In the title of Iñárritu’s movie, perros is an adjective (meaning “stubborn” or “dogged”),

but the film also reflects the word’s meaning as a noun, in its dogs, which

embody both the best and worst attributes of the human characters. The animals

also stand for loyalty, abandonment, betrayal, and redemption.

Octavio’s story

presents a character defined by a sort of essential duality: he is a

mild-mannered man who turns out to possess a killer instinct. When he decides

to run away with his sister-in-law, he makes his rottweiler, Cofi, take part in

dogfights. In a way, Cofi becomes the embodiment of Octavio’s newfound

ruthlessness. As a consequence of this transformation, Octavio commits a crime

that forces him to flee, precipitating the accident that changes the lives of

all the film’s main characters. In the second segment, Valeria’s lapdog,

Richie, mirrors her predicament. Following the accident, multiple fractures

confine her to a wheelchair, and she becomes aware of how dependent she is on

her glamorous image of herself. Daniel also worships her body, but now that she

has become imprisoned by that body, their loving relationship loses its

foundation. While Valeria recuperates, Richie falls through a hole in the

apartment floor. At night, she and Daniel hear the whimpers of their trapped

dog, reminding them of the state of their relationship.

The dog most integral to El Chivo’s story is for him both a double and a

redeemer, leading him to confront his past and recognize his own degradation.

El Chivo lives surrounded by street dogs; they are the only recipients of the

affection he has repressed for years. He does not hesitate to take in Octavio’s

injured rottweiler and nurse him back to health. But Cofi—like El Chivo—has

been trained to annihilate. Out of habit, he kills the rest of El Chivo’s

canine “family.” The hit man’s first impulse is to shoot Cofi, but he sees

himself reflected in the dog. He forgives him and, in so doing, forgives

himself. He leaves behind his mercenary life and, in the film’s closing image,

walks with the dog toward the horizon.

Courtesy of Alejandro G. Iñárritu