Downpour: Furtive Glances

An artist, critic, and scholar highly respected in his native Iran but too little known in the West, Bahram Beyzaie is a gifted autodidact of traditional and modern theater and performing arts, and of cinema. Born in Tehran in 1938, he went on to write his first plays while still in high school, and by 1965 had published his now seminal A Study on Iranian Theatre, which demonstrated his deep knowledge of the variety of forms of theater practiced in the region since ancient times. In 1971—after a decade in which he wrote and directed many plays, a number of which also drew from his continued scholarship on theatrical traditions—Beyzaie undertook to make his first feature film, Downpour (Ragbar), a slyly inventive romantic drama produced independently from his own screenplay. His subsequent movies, made both before and after the 1979 Islamic Revolution—including Stranger and the Fog (1976); Bashu, the Little Stranger (1986); and Killing Mad Dogs (2001)—consolidated his reputation as one of the foremost auteur directors in Iran. But Downpour remains one of his best-known and best-loved works, and it helped to inaugurate the Iranian New Wave, which placed the country on the world map of engaged cinema.

If culture and cinema in the United States are primarily commercial, in Iran they are principally political, even the commercial culture and cinema. Under the last shah (1941–79), the state constituted both a powerful friend and pillar of support for the film industry and an irresistible foe and punching bag for the auteur directors, as it continues to do under the ayatollahs who came to power after him. In the late sixties, Iranian critics relentlessly decried the low quality of the films made in the popular abgushti (stewpot) and luti (tough guy) genres, on the grounds that these commercially made movies actually lowered film-industry profits, along with the country’s taste culture and national prestige.

By August 1968, a more enlightened government had decided that to control cinema it was necessary not only to censor it but also to patronize it. On August 21, Prime Minister Amir Abbas Hoveyda told a gathering of the Movie Artists Syndicate, “Iranian movies must have originality and be inspired by Iranian history.” He then announced that his government was designating a sum of ten million tomans (nearly equivalent to $1.4 million at the time) in the fourth national development plan for the film industry. One ironic and felicitous result of this investment was the emergence of a “New Wave” (sinema-ye mowj-e no) countercinema, at odds with both the commercial genre cinema and the government that largely provided its own funding. If box-office revenue and state censorship shaped the Iranian commercial cinema of the fifties and sixties, the New Wave cinema of the seventies was defined by its complex relationship with the state, which both funded and censored it; by the authorial status of the New Wave directors, many of them trained in the West; and by their collaboration with dissident, leftist writers.

“A synergy among filmmakers, dissident writers, and trained actors helped to drive the New Wave films’ stylistic innovations and social relevance.”

Among the Western-trained New Wave directors were Fereydoun Rahnema, Farrokh Ghaffari, Kamran Shirdel, Parviz Kimiavi, Sohrab Shahid Saless, and Hajir Darioush (trained in Europe); and Bahman Farmanara, Dariush Mehrjui, and Khosrow Haritash (trained in the United States). Self-taught or domestically trained directors included Beyzaie, Masud Kimiai, Naser Taghvai, Parviz Sayyad, Amir Naderi, and Abbas Kiarostami, whose deceptively simple but profoundly layered films pushed him into the pantheon of world cinema. Together, these two groups formed an authorial force whose work undertook a more critical examination of Iranian society and history than had been attempted on-screen in the past. The almost simultaneous emergence of a new generation of socially conscious leftist and secular writers whose works these directors adapted or with whom they collaborated on original screenplays—such as Gholam-Hossein Saedi, Sadegh Chubak, Houshang Golshiri, and Mahmoud Dowlatabadi (as with the directors, an exclusively male group)—also helped contribute to the abandoning of traditional commercial genre formulas and narratives in favor of enhanced realism, character interiority, and narrative continuity and coherence. Additionally, the New Wave films benefited from the talents of a new generation of theater actors, trained in modern representational acting, many of whom worked in the Ministry of Culture and Arts’ theaters. In fact, this was an important ancillary effect of the ministry’s increased support of cinema starting in the late sixties: filmmakers’ access to its cadre of skilled actors.

This synergy among filmmakers, dissident writers, and trained actors helped to drive the New Wave films’ stylistic innovations and social relevance, features that had been in short supply in the Iranian commercial cinema of the previous decades. Of the movement’s many artistic talents, Beyzaie stood out as one of the most protean. Turning his attention to filmmaking after achieving renown as a scholar and playwright, he made a couple of shorts for the semigovernmental Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults before writing and directing Downpour. This feature—produced by Barbod Taheri, who also served as cinematographer—immediately placed Beyzaie among the top New Wave directors, and established a theme he would revisit in later films, among them Stranger and the Fog and Bashu, the Little Stranger: a community’s fear of an outsider (or group of outsiders) who has arrived in their midst, upsetting that community’s traditional harmony and relations of power, and unleashing strong reactions of attraction and repulsion. Only after the stranger’s removal can the community return to an apparent, if uneasy, harmony.

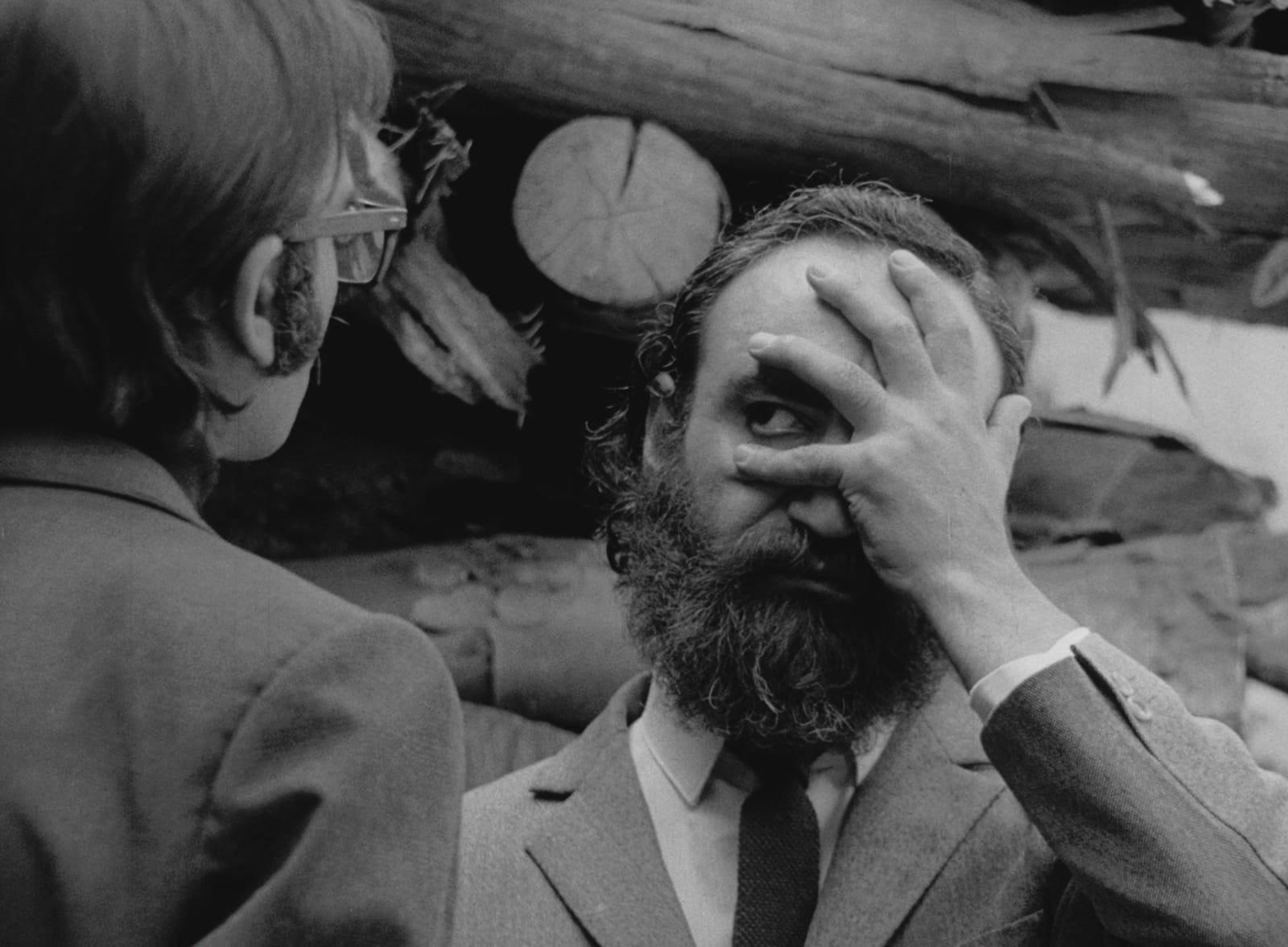

Downpour weaves a rich tapestry involving a budding love between a new teacher, Mr. Hekmati (Parviz Fannizadeh), and Atefeh (Parvaneh Massoumi), the sister of one of his students, in Tehran’s poor South End. The teacher’s public arrival into this community, with all his belongings loaded on a cart, is observed cautiously by the neighbors and good-naturedly by the noisy schoolchildren. Soon the students spy on Atefeh complaining to Mr. Hekmati about his punishing of her brother, a scene that the schoolchildren, with their eyes glued to the classroom windows, interpret with knowing smirks as intimacy between the two. (The film is imaginative and clever in its many depictions of such acts of looking.) This conjecture by the students soon mushrooms into a neighborhood rumor, and the exchanges of various knowing and derisive gazes and sarcastic comments among Mr. Hekmati’s fellow teachers. Thus, before he and Atefeh own up to their love for each other, these feelings are already clear to the whole neighborhood, as well as to the viewer.

At the same time, Atefeh and her family are beholden to the neighborhood tough guy, Rahim (Manuchehr Farid), a burly butcher who has been helping them in various ways in hopes of winning Atefeh’s hand in marriage. But she has no interest in, or expectation of, being swept off her feet. With Atefeh—unusual in the context of the Iranian cinema of the time for being an independent young woman who has a job, using her position as a seamstress to support and care for her brother and sick mother—Beyzaie introduced what was for him the first of many strong, distinctive female protagonists. His films Ballad of Tara (1979) and Death of Yazdgerd (based on his own acclaimed play, 1982) were long banned in Iran, apparently partly because of their representation of unveiled women.