In memory of D. A. Pennebaker (1925–2019)

1.

The great documentary filmmaker D. A. Pennebaker was motivated to shoot by curiosity. He loved music and friendship, and he had an understanding that everything he filmed recorded histories both personal and cultural: Robert Kennedy and Sammy Davis Jr. singing “Jingle Bells” to New York City schoolchildren (Jingle Bells); Bob Dylan’s 1965 UK tour, his last as an acoustic artist (Dont Look Back); and Otis Redding at the Monterey International Pop Festival in 1967, six months before his tragic death (Monterey Pop). When his friend Norman Mailer asked him to film the “Dialogue on Women’s Liberation,” a debate at New York City’s Town Hall theater to be moderated by Mailer, Pennebaker was determined to make it happen.

2.

Pennebaker and his fellow camera operators (Jim Desmond and Mark Woodcock) eventually filmed the event—which took place on April 30, 1971—without official permits. This accounts in large part for the rough form of the footage, which sat on the shelf at Pennebaker’s office until he showed it to Chris Hegedus in 1976. At that point, Pennebaker had recently hired Hegedus to edit miscellaneous material that he and his collaborators had accumulated. As soon as she saw the Town Hall footage, she knew that a film had to be made with it. At a 2004 screening of Town Bloody Hall at New York’s National Arts Club, Pennebaker described the film as a “triumph of content over aesthetics.”

3.

The “Dialogue on Women’s Liberation” was produced by Shirley Broughton for the Theater of Ideas, an organization that she founded in 1961. A ticket to the event ran a costly twenty-five dollars, and the crowd was made up of New York’s intellectual elite. Among the audience members were writers Susan Sontag, Elizabeth Hardwick, Cynthia Ozick, Betty Friedan, Gregory Corso, and Anatole Broyard.

4.

Mailer had hoped to debate Kate Millett, whose Sexual Politics (1970) investigated the subjugation of women in literature and art by male artists (Mailer included). When Millett refused to take part, Broughton scrambled to find other female critics to face off against Mailer.

5.

Not long after the publication of “The Prisoner of Sex”—his response to Millett, which first appeared in the March 1971 issue of Harper’s—Mailer described his essay as “probably the most important single intellectual event of the last four years.” His views later changed. In a 2004 interview featured on our edition of Town Bloody Hall, Mailer explains his obliviousness to the intensity of the women’s liberation movement: “I was doing everything they wanted me to do to fulfill the notion of the male gender being assertive, aggressive, stupid, and oppressive. It wasn’t my brightest night.” As for the event itself, he says participant Jill Johnston turned his hair gray that night.

6.

Millett wasn’t the only prominent feminist to refuse Mailer’s bait. Betty Friedan, author of The Feminine Mystique and cofounder and then president of the National Organization of Women (NOW), also declined to participate, but she pressured Jacqueline Ceballos, head of the New York City’s chapter of NOW, to take her place. Other prominent figures in the women’s liberation movement, including Gloria Steinem and Ti-Grace Atkinson, also declined Broughton’s invitation. The then relatively unknown Germaine Greer, an Australian intellectual whose The Female Eunuch had just been published in the United States, was in the country touring with the book, and was introduced to Mailer via a mutual friend, the filmmaker Dick Fontaine, resulting in her seat at the table.

7.

Much was made of the onstage chemistry between Greer and Mailer. In her book We Must March My Darlings: A Critical Decade (1977), literary doyenne Diana Trilling—also a participant in the Town Hall event—maintained that Greer “consented to be on the panel [because] she wished to meet Mailer, and go to bed with him.” In an interview also on our edition, Greer acknowledges the attraction between her and Mailer but notes that she was simply not interested in sleeping with him. She also confirms that the enmity between her and Trilling never ended.

8.

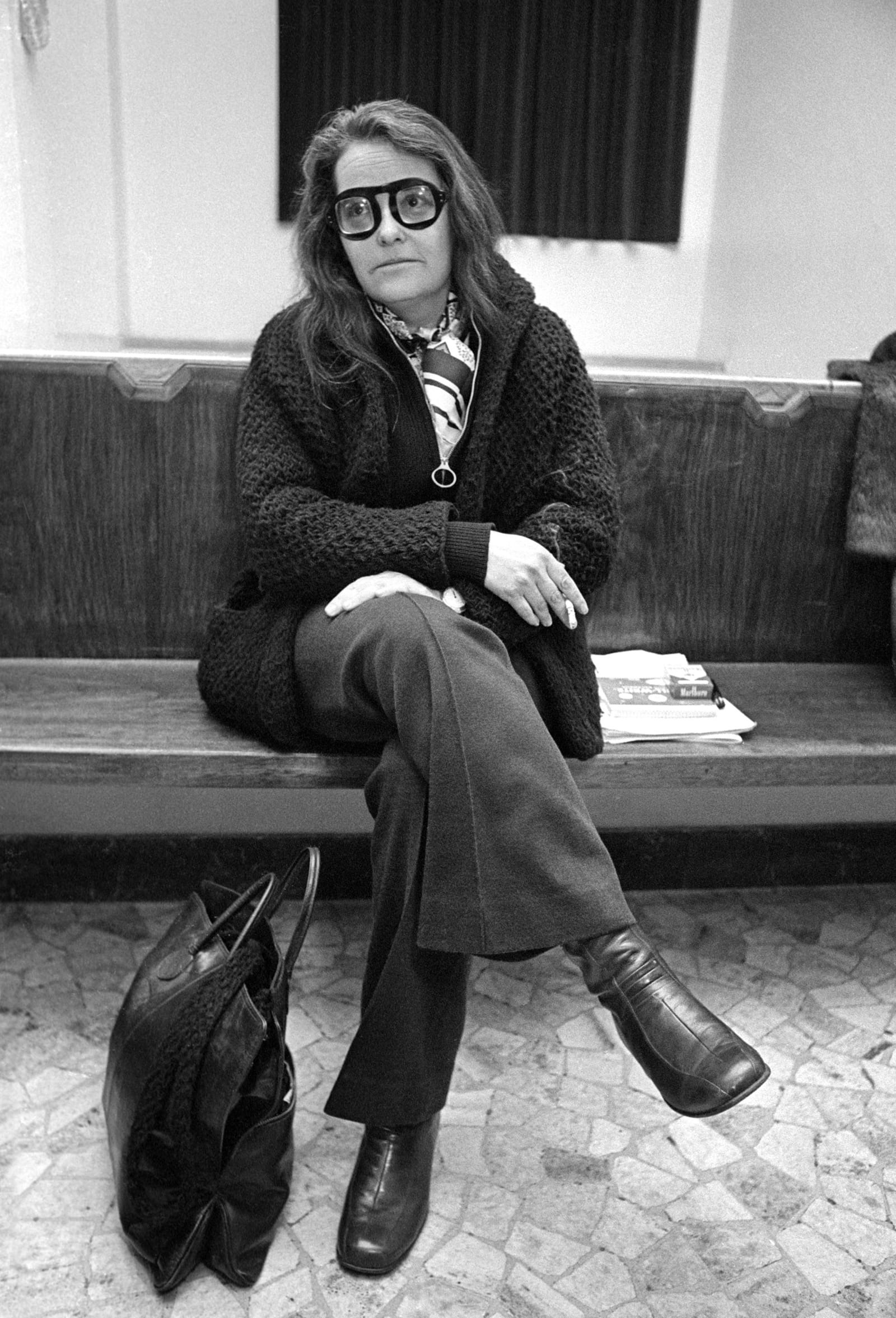

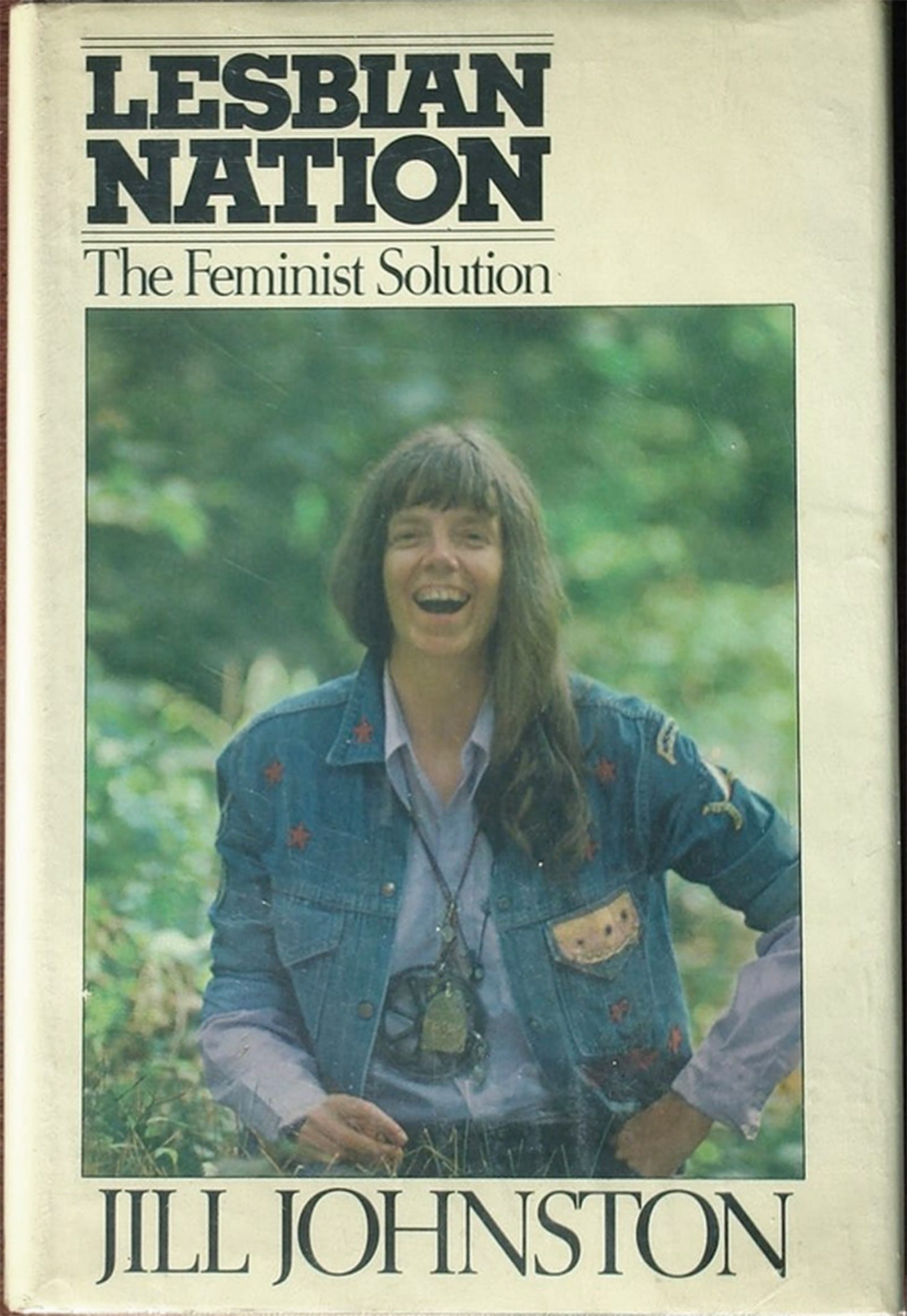

Jill Johnston, a leader of the lesbian separatist movement, publicly came out in 1971 in a column in the Village Voice, where she was a dance critic. Her book Lesbian Nation (1973) encouraged women to identify themselves as lesbians and argued that lesbians were essential to the feminist movement. She was also well known for her performative persona. Once, bored at a poolside press conference given by Friedan, she stripped off her top and took a swim.

9.

At the premiere of the film—at the Whitney Museum of American Art on April 3, 1979—Johnston told Hegedus, “Chris, I was the best thing in the film, wasn’t I?” Indeed she is. (At a later screening of the film, Johnston wryly confessed that she had had a few drinks at the Algonquin Hotel before going onstage.)

10.

Though the first project they completed together as codirectors was Energy War (1977), a documentary series about President Jimmy Carter’s battle to pass a natural-gas bill, it was Town Bloody Hall that truly marked the beginning of the creative partnership between Chris Hegedus and D. A. Pennebaker, who also married in 1982. They made over twenty-five films during their forty-three years working together, including DeLorean (1981), The War Room (1993), and Kings of Pastry (2009).

More: Production Notes

10 Things I Learned: Raging Bull

While working on our edition of Martin Scorsese’s 1980 masterpiece, producer Abbey Lustgarten found out how the director achieved some of the movie’s most evocative visual and sonic effects.

The Evolution of a “Superpig”: Designing Okja, from Start to Finish

Both intimidatingly massive and deeply sympathetic, the creature at the heart of Bong Joon Ho’s meat-industry fable is the product of a close collaboration between the director and artist Jang Hee Chul.

10 Things I Learned: Rouge

The producer of our edition of the masterful 1987 melodrama tells the stories of some of director Stanley Kwan’s legendary collaborators, including superstars Anita Mui and Leslie Cheung.

A Movie About Leaving Earth

On Earth Day, we celebrate Al Reinert’s For All Mankind, a groundbreaking documentary that is as much a reflection on our planet as it is a chronicle of space travel.