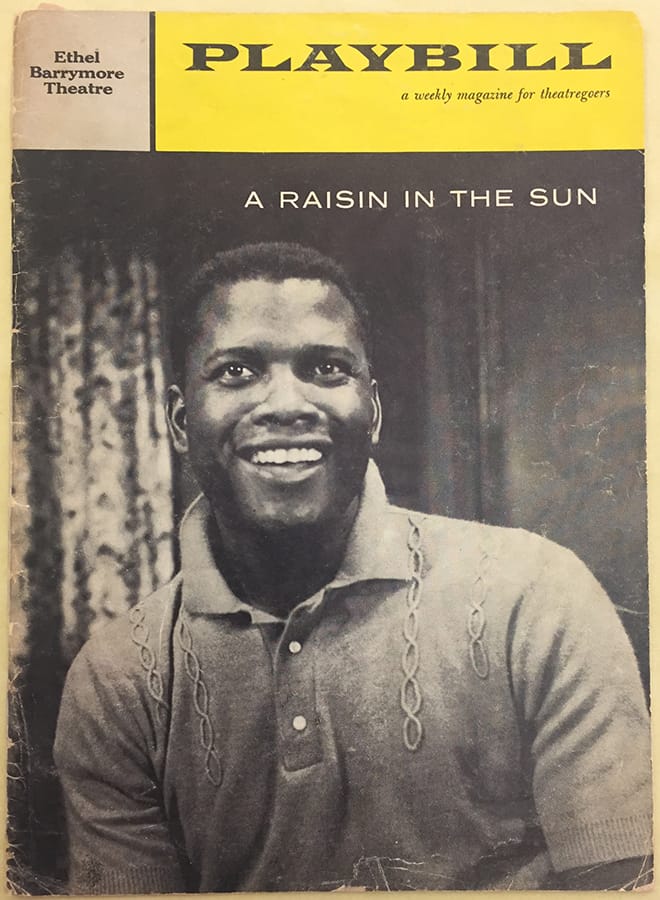

A Raisin in the Sun: Resistance and Joy

In a 1964 letter to the editor of the New York Times, playwright Lorraine Hansberry wrote about different modes of resistance that she had witnessed within her own family: “I [. . .] remember my desperate and courageous mother, patrolling our house all night with a loaded German luger, doggedly guarding her four children, while my father fought the respectable part of the battle in the Washington court.” Hansberry is referring here to the preparations her mother, Nannie Hansberry, made to defend her black family from violence after moving into a primarily white neighborhood in Chicago in 1937, and to the suit against the city’s restrictive housing covenants that her father, Carl Hansberry, with NAACP lawyers, took all the way to a Supreme Court victory in 1940. She demonstrates a keen awareness of the multiple ways in which people of African descent in the United States have fought for their right to live with dignity, calling into question the idea that there is any difference at all between radical and respectable resistance.

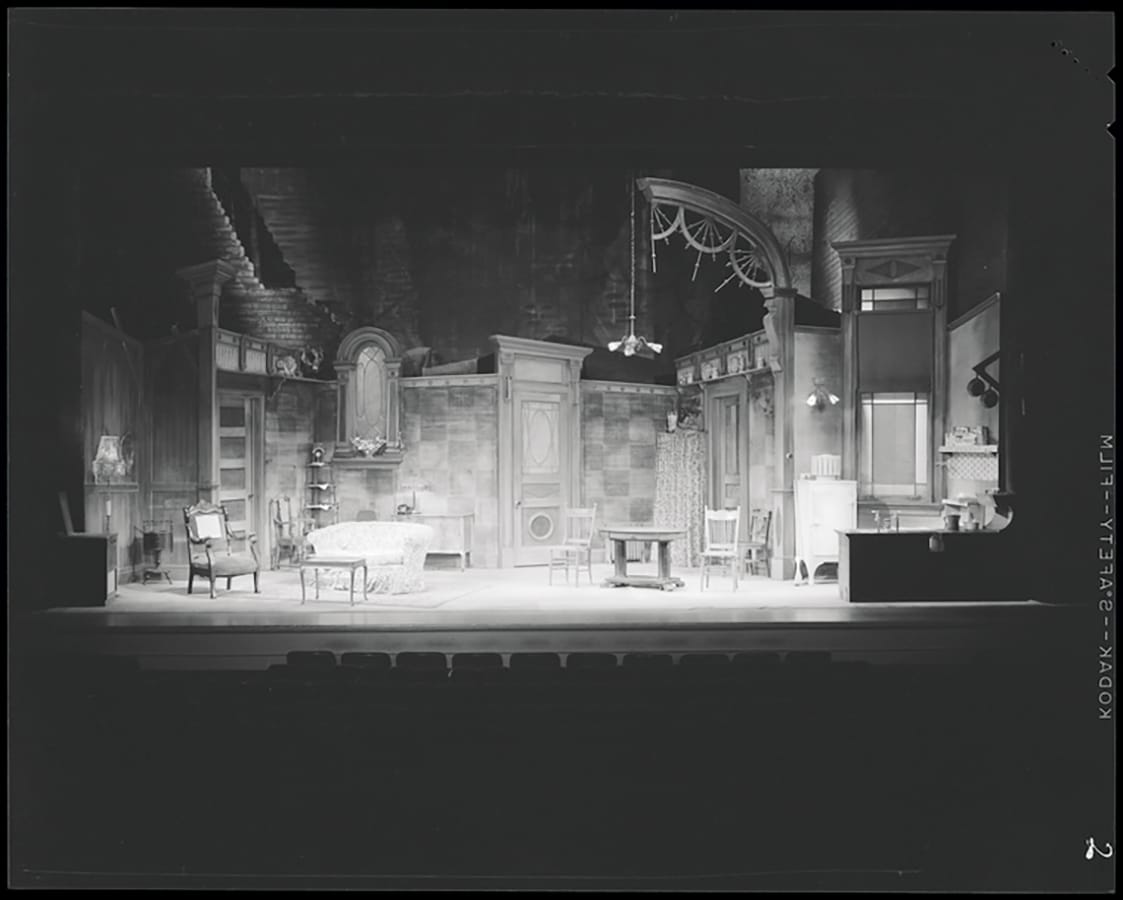

Hansberry’s 1959 play A Raisin in the Sun and its 1961 film adaptation (for which she also wrote the screenplay) similarly highlight various strategies of African American resistance. Simultaneously fighting overlapping systemic oppressions, the members of the Younger family refuse to defer their dreams (to reference the same Langston Hughes poem from which the play and film take their title), instead affirming their belief in themselves and one another through moments of shared joy, connection, and nurturing. The film version was the second theatrical feature by director Daniel Petrie, a veteran of filmed television plays who treats the material with respectful restraint.

Lorraine Hansberry