Constant Compass: Uma Das Gupta in Pather Panchali

There’s something cool, even implicative and spooky about being named after a girl in a movie. Something sort of unforced, like a quirk I get to keep but was uninvolved in forming. It’s as though my love of film predates me, is beyond my control, and here I am, the product not just of my parents but also of their taste. Because the Durga I’m named after is the Durga in Pather Panchali (1955)—the first installment in Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy, and one of the greatest films ever made.

I’ve always felt connected to this character, the mischievous young girl with a sweet tooth who steals her neighbor’s fruit and is kind when no one else is to her old, hunched-over auntie. But since watching the movie again last month, I’ve wondered whether I was named after the character or, rather, Uma Das Gupta’s cautiously expressive portrayal of her. It’s easy to conflate the two, since Das Gupta never appeared in another film, and Pather Panchali’s realist qualities often lead you to think you are watching a documentary. But this time around, I was struck by the careful artistry that went into her performance.

Headstrong and completely unbothered by what people might say, Durga lives in a rural Bengal village with her mother, Sarbajaya, a woman whose nagging instinct to care means she appears near-creased with worry. Durga’s father, Harihar, a Brahman priest struggling to provide for his family, is easygoing to a fault. His outlook or, at the very least, his confidence feels out of sync with his wife’s fraught manner.

For most of Pather Panchali, we experience Durga in her role as older sister to her younger brother, Apu. She is his compass: the first face he sees when he wakes up in the morning, the hand that slaps him when he borrows tinsel from her toy box without asking, the tongue that sticks out and makes him smile. They provide for each other a sense of belonging, an affinity that only siblings share. Durga seems not just powerful but prepared for anything while Apu is drawn to whatever he can push through a crowd and get up-close to. His sister’s affections are revealed by how gently she levers open the world for him. She shows him how it’s possible to marvel not only at rain and trains but also at the calm that anticipates the rain and the before-rumble that says: here comes pure speed cutting through a kaash field, leaving us behind.

Each frame in the film reflects a seemingly shared state of mind of the very young and the very old—innocence that grabs a hold, understanding that doesn’t make too much of itself. Long stretches of wordlessness—as when the two children are trailed by a trotting dog, their mini-convoy reflected upside down in a river—create an environment in which the characters are not contriving anything. They live. They do. They are. Ray illustrates how the young, who are new to the world and are still feeling around its edges, and the elderly, who have long since come to terms with its limitations, understand and appreciate life in a more immediate way.

It doesn’t surprise me that when it came time to shoot, Ray, who spent years working in graphic design as an art director at a Calcutta ad agency before venturing into film, did not rely on a script. He’d prepared sketches in black ink, and the dialogue was stored in his head. The characters’ actions occasionally look like stains on a page. One sketch of Apu and Durga standing between two towering trees captures their smallness surrounded by nature’s great big shelter. Another shows them racing into the frame from the bottom right corner, the sky tarnished with dark, imposing clouds. Ray’s sketches are more than mere concepts; they look like how a great film feels long after you’ve left the theater: just shadows, joy. The lack of a script seems to anticipate the audience’s reaction: at a loss for words.

Das Gupta’s performance haunts, and not just because of the tragedies that befall her character. It’s so much more than that. While Durga doesn’t overwhelm the screen, the way she grins kindly at Apu, or holds his chin while combing his wet hair, or dances freely during a monsoon—these movements of a girl—fine-tune the film. Her mischief is significant to its rhythm. Her attitude is never withdrawn, though her secret wants and her hesitations, like the way in which she doesn’t readily join the other girls, are Pather Panchali’s most memorable tensions.

When Durga is chewing sugarcane or staring off—never at some random middle distance, but far off, with a specific target—she is not just Durga but a cowboy. Huck Finn. A groundskeeper. Wendy showing her Lost Boys the way. In the role, Das Gupta is nothing like the girl who showed up to her audition for Ray wearing pearls.

Sticking her tongue out, as Durga does throughout the film, makes Das Gupta look just a little mad. Like a girl who isn’t necessarily crazy but has perhaps wisely chosen to abstain from conforming to what’s expected. I’ve only ever seen Gena Rowlands, in A Woman Under the Influence, stick out her tongue like that. It’s funny. Strange.

Das Gupta’s keen portrayal, which channels Ray’s gift for close observation, has everything to do with seeing without being seen. She crouches, climbs, and ducks under. She peers inside, looks both ways; she listens before she looks. Durga can fold herself into a ball or just as quickly unfold herself and race ahead. Some bodies betray their private hectic, and Durga’s rattling ingeniousness—seen in the relationship she nurtures with her auntie and the games she imagines for Apu—is what makes Das Gupta’s performance not just moving but connective. She romances you.

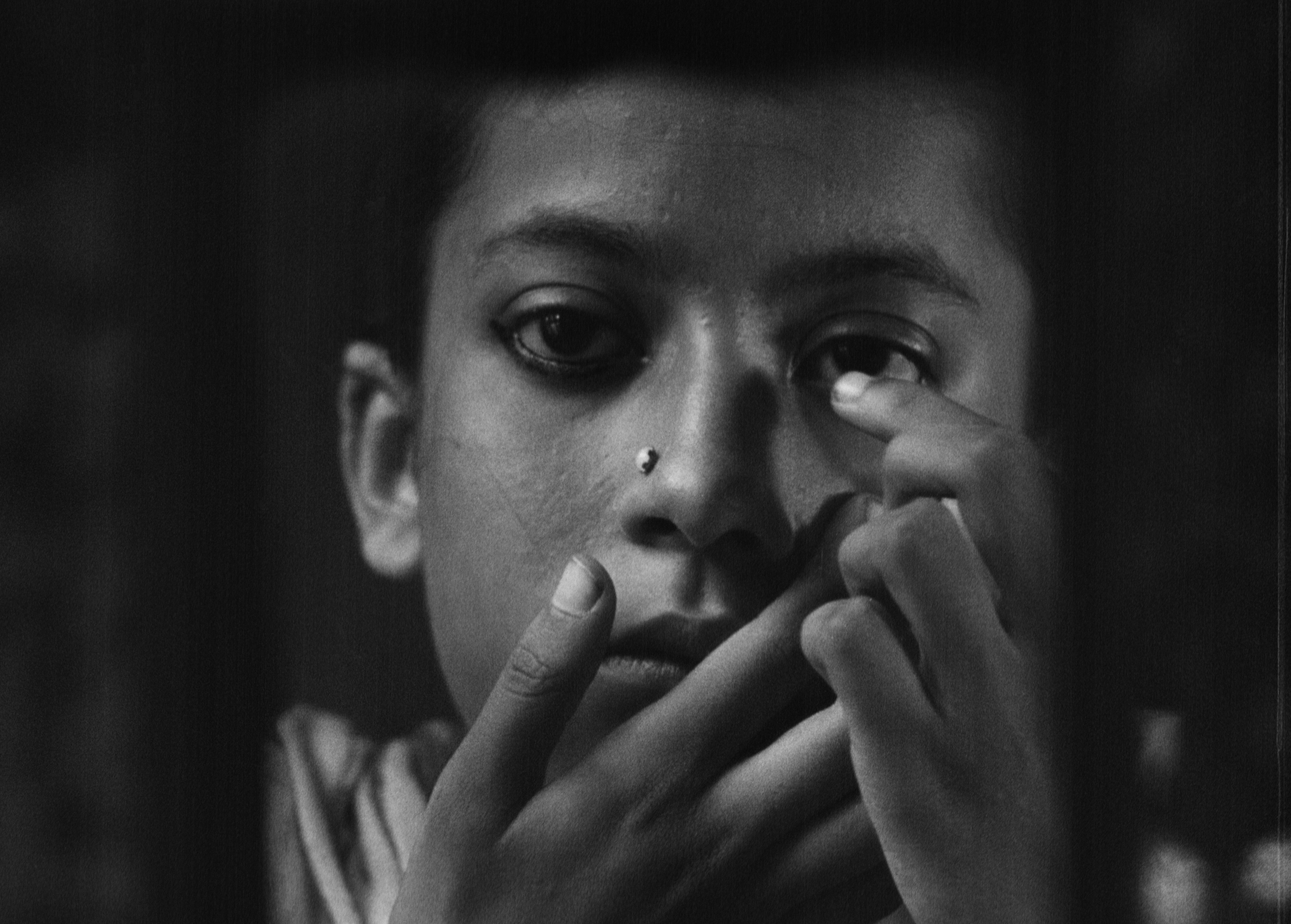

Late in Pather Panchali, she gazes at her reflection in a mirror, and it’s the first time we watch Durga perceive herself, studying the round elegance of her face and the heavy fall of her hair. She paints thick kajal under her eyes, and it’s only here that we are more formally introduced to her. Durga looks susceptible and we feel it, and it becomes infinitely clear, if it wasn’t already, that Das Gupta has been carrying the film forward, maintaining its force with her small frame.

Ray’s definition of a star as someone on-screen “who continues to be expressive and interesting even after he or she has stopped doing anything” applies so acutely to Das Gupta’s regenerative qualities. Her presence is somehow transformed even after her character is gone. Her willingness and kindness, her cheeks that wonderfully refuse gloom—all of these qualities persist in the landscape of the film.

Because there she is—even if she isn’t—beside Apu, following him to the pond. There she is—plop!—the necklace he tosses into the water. There she is—the pond weeds—opening and closing around the necklace as it sinks, as if swallowing her secret, protecting her name.

Durga is the water-skaters, the dragonflies, the lilies. Durga is the train passing through the kaash field; she is the show of black smoke that lingers in its wake. She is the leftovers of a family forced to move on, the home once the home is no more. She is also there with Apu, a boy no longer in possession of his compass but equipped instead with a stare that is already wiser. Apu continues, alone but not exactly, because there she is. Look.