Archive Fever Dreams: Inside the Bob Dylan Archive

There’s no traceable origin for the archivist’s impulse. It’s ascendant in late antiquity with the cult of the saints, their bones and artifacts collected, a tacit belief that holy relics, held dear, help us to transcend the divide between the secular and the sacred. Since that time, and to Nietzsche’s eternal horror, the collecting and cataloging of our past hasn’t ever abated. If anything, we’ve become hysterical about it, to the point that Western society in the first decades of the twenty-first century is consumed by archive fever. One explanation for this, among several, is that the digital world’s eclipse of the analog has forcefully unleashed a foreboding sense that something in the foundation of our existence is becoming irretrievably lost. In preserving the past, our romantic hope is that we are making some small purchase on the future; that, in years to come, a brilliant individual will survey the detritus of our collected efforts and advance human understanding, asking questions that no one had ever before thought to ask. The net result of this is that someone like myself has been able to earn a living “archive hunting.” The day-to-day work of this job falls somewhere between the earnest bumblings of the protagonist in Henry James’s The Aspern Papers, the deft salesmanship of Herman Melville’s The Confidence-Man, and the intrepid archaeology of Raiders of the Lost Ark—only with a lot less blood.

I found my way into this kind of work not by training but by happenstance. In early 2000, recently out of college, I began showing films at International House Philadelphia. It was there, organizing film retrospectives dedicated to the works of author (and part-time filmmaker) Norman Mailer, Cinema 16 founder Amos Vogel, and, most fatefully, documentarian Albert Maysles, that I soon began assisting all three in the organization of their respective archives. When, in 2005, Al offered me a job at Maysles Films, I seized the opportunity and moved to New York.

A short while later, in early 2007, I made one of the better decisions in my life when I cold-called rare bookseller Glenn Horowitz after reading a New York Times profile of him and asked if he would assist with the placement of the Maysles archive. Glenn is of a type that doesn’t really exist anymore. His professional roots go back to the final days of Book Row, that stretch of Fourth Avenue right below Union Square that, for decades, was the bookselling epicenter of Manhattan. Glenn had a hand in building up the rare-book room at the Strand, creating its salonlike atmosphere while also cultivating clients that would help to make his reputation as one of the most successful booksellers—and later, archive agents—in the history of the profession.

Not only is Glenn particularly adept at navigating the complex forces swirling around archival collections—the sometimes contradictory aims of artists, their estates, curators, and collection directors—he is, above all, a closer. I didn’t come from a business background, and he was the first person to instill in me a sense that there was a way to organize what I was doing and make an interesting life for myself out of it. It was probably the most important and sobering advice I’d gotten up to that point.

When, in early 2014, Glenn asked for my assistance on the Bob Dylan Archive, it felt like the culmination of a lot of the work we’d been doing together. A couple of years after we initially met, I’d assisted him on organizing Spalding Gray’s papers. From there we began a series of collaborations—the aforementioned archives of Albert and David Maysles, as well as the collections of Nicholas Ray and D. A. Pennebaker and Chris Hegedus, among others. Generally, the projects we’ve taken on together have been “nontraditional,” in the sense that these collections aren’t strictly text-based but include film, video, audio, artwork, ephemera—and Dylan’s archive was no exception.

Given the secrecy surrounding Dylan’s working methods, everything in this collection was a discovery in some sense, none more so than the very fact that Dylan had managed to hold on to so much stuff, most notably the working drafts of his songs. Volumes have been written about Dylan’s mercurial genius, but the amount of writing in the archive suggests that, whatever his substantial native talents, his songs didn’t arrive fully formed but were teased out through a prodigious writer’s discipline. His drafts cover every surface—matchbook covers, napkins, and countless pages of hotel stationery—all ruthlessly self-edited, his songs seemingly never “finished” but always in the process of becoming. Whether on the page, in the studio, or onstage, they were continually reformatted to fit his mood or the times.

Dylan is unique among modern recording artists in that he owns all his master tapes, which means virtually every studio session from each of his albums is present in the archive. With so much material available to us, we have the ability to telescope in on the genesis of his recorded material, which includes numerous takes, alternate versions, and unreleased songs. The sessions are the equivalent of what you might call audio verité—essentially an aural documentary on the making of Dylan’s landmark records.

The archive boasts hundreds of hours of live recordings, going back to Dylan’s earliest coffeehouse days and continuing into his recent tours. There are many instances in the archive where a song can be studied from its initial iteration on paper, to the moment Dylan first stepped to the microphone to record it, through to its reinvention over several decades onstage. A good example of this is “Tangled Up in Blue,” from the 1975 album Blood on the Tracks—it’s a song that began on paper with the title “Dusty Sweatbox Blues,” whose first studio take was a solo acoustic performance; it was ultimately released on record with a full band and has since had its lyrics and tempo radically altered in live performance. The ability to trace out this evolution is among the archive’s greatest strengths.

As another example, take “Ballad of a Thin Man” (from 1965’s Highway 61 Revisited), whose original typescript shows numerous handwritten changes and additions. Here the song’s central refrain, “Because something is happening here / But you don’t know what it is,” omits its famed coda—“Do you, Mr. Jones?”—but includes several lines cut from the final lyric, such as “Your face is so serious / How fantastically absurd / You ask obnoxious questions and expect answers in one word.”

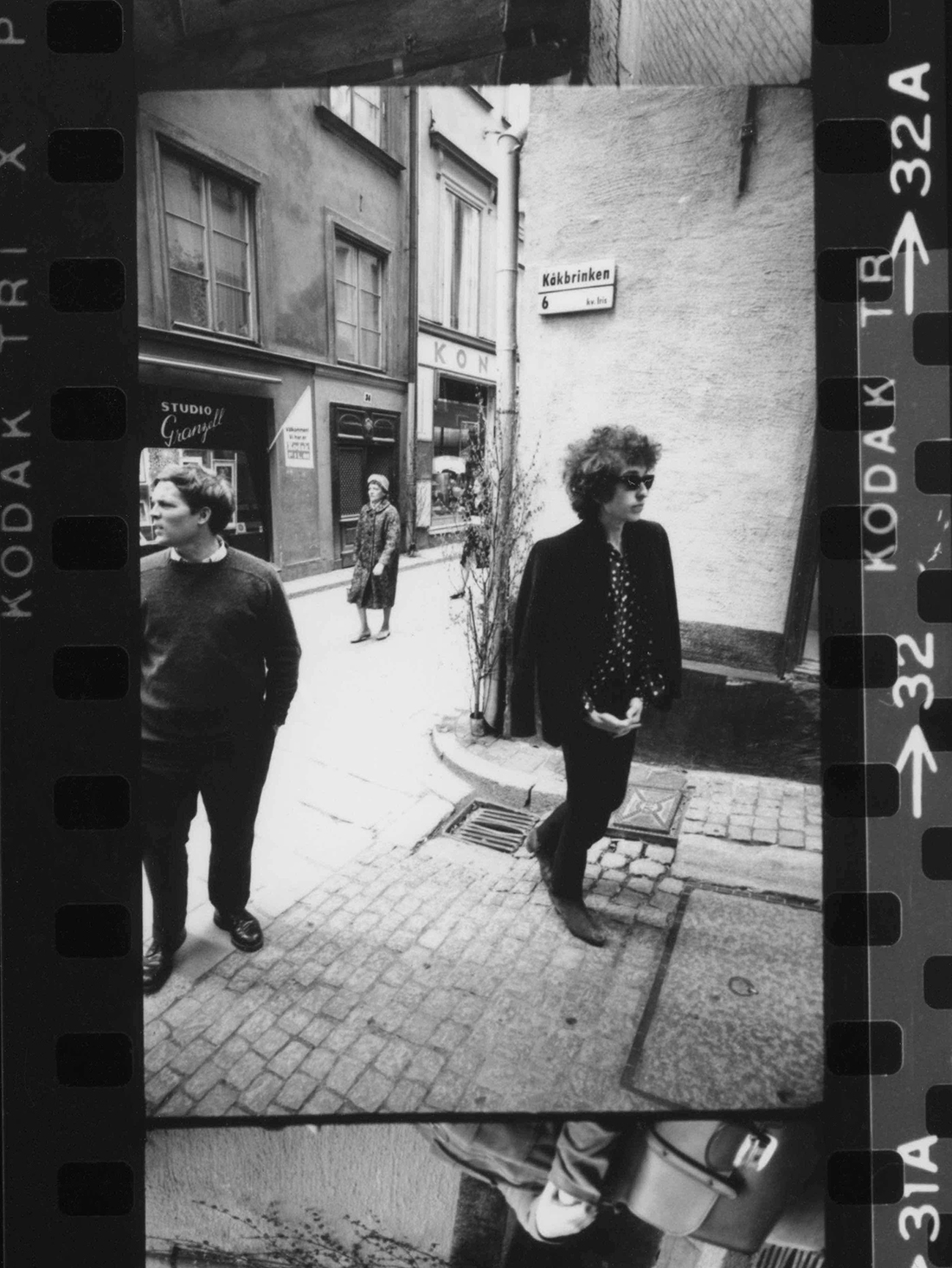

The archive also contains an impressive amount of film and video material. Having assisted D. A. Pennebaker with his archive, I was immediately struck when working on Dylan’s archive by the hours of largely unseen outtakes it includes from Pennebaker’s Dont Look Back (shot in 1965 but released in 1967), along with the footage Pennebaker shot during Dylan’s 1966 European tour. (The latter was edited by Dylan and Howard Alk and released as Eat the Document in 1972, and used, in part, by Martin Scorsese in his 2005 documentary No Direction Home.) Shot nearly a year after Dont Look Back, the footage from 1966 forms a sequel of sorts, with the same “characters” returning: Albert Grossman; Bobby Neuwirth; even erstwhile concert promoter Tito Burns, who are all filmed here in the rich-hued, 16 mm color reversal stock that Al Maysles would use a few years later to shoot Gimme Shelter.

The duration of the uncut reels gives one a better sense of these tours in real time, the circus surrounding Dylan no less suffocating in 1966 than it was in 1965, and includes numerous candid, illuminating, moments off-stage alongside some devastating concert performances. One such scene is of Dylan, on the precipice of going fully electric, in the Savoy Hotel in early May 1965, watching John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers perform on television. Dylan is taken with the guitar player, who he says looks “just like Wyatt Earp” (in actual fact it was a twenty-year-old Eric Clapton, who had joined the band only weeks earlier). Turning to Neuwirth, he says that Mayall has promised that he and his band will back him up in concert and play “Maggie’s Farm” “just like the record.” This never came to pass, though the band did sit in for one brief studio session with Dylan a little later that month. Nevertheless, this scene is a portent of things to come for Dylan. Upon returning to America, he famously recruited guitarist Michael Bloomfield and other members of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band to perform with him at the Newport Folk Festival a couple of months later, on July 25, the night Dylan “went electric.”

It wasn’t only the London music scene firing Dylan’s imagination. As this previously unseen outtake from the archive reveals, England’s sartorial taste was also making a lasting impression.

Since I had the incredible fortune of being named curator of the Bob Dylan Archive, my work on the collection has been ever-evolving and so too my knowledge and appreciation for what it contains. I’m currently dividing my time between Tulsa and New York City, and my main priority at the moment is helping to make the collection accessible to scholars, researchers, and students at the Helmerich Center for American Research at Gilcrease Museum.

One might rightly wonder if there will be a future to benefit from any of these efforts. No matter how dire the geo-environmental and political outlook, to say “no,” I believe, is to give in to the worst kind of cynicism. If nothing else, Dylan being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in October was an unsuspected but welcome confirmation that his poetry still has a valued place in our world. If none of our efforts mean anything, then one has to ultimately come to the conclusion that everything surrounding us is absurd—a bleak position, one inhospitable to serious work and thought. The archivist’s impulse, whatever the taproot, affirms that what has come before can be made eternally alive and present, provided, as Nietzsche reminds us, that what we are celebrating in our own history is not an end in itself, but a means of serving life through a fundamental continuity with the strengths of our past. In this regard, preservation is the enemy of nihilism and evinces a simple hope: that the future lasts forever.

All photos courtesy of the Bob Dylan Archive, Helmerich Center for American Research, University of Tulsa