Talking with Screenwriter Hung Hung About A Brighter Summer Day

Twenty-five years after it first appeared on the international film festival circuit, Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day is finally being released on home video in the United States. An outraged counterpart to his beloved (and more widely available) swan song Yi Yi (2000), this nearly four-hour epic refracts the turbulent political atmosphere of 1960s Taiwan through an ongoing war between rival youth gangs and the vast, intergenerational web of characters that surrounds them. Since its limited theatrical release in the early 1990s, Yang’s masterwork has circulated primarily through grainy bootlegs and ultra-rare repertory screenings. In this new restoration, it is now ready to be discovered anew as one of the most virtuosic and politically urgent works of the New Taiwan Cinema.

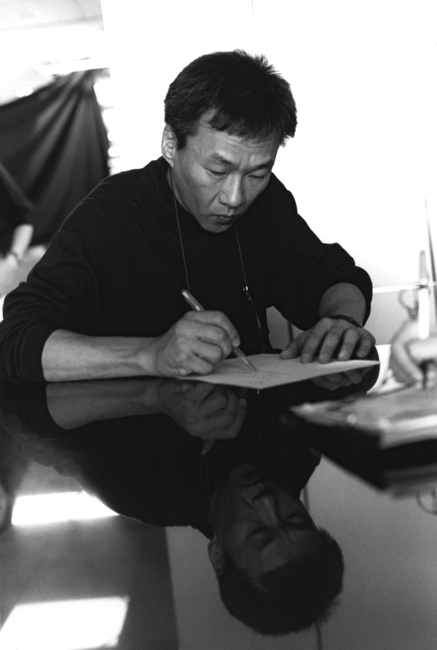

Hung Hung (credited in A Brighter Summer Day as Yan Hong-ya) is a Taiwanese poet, filmmaker, and dramatist who was a close collaborator on several of Yang’s films and served as one of his three screenwriting partners on A Brighter Summer Day. Hung first worked with Yang on the director’s 1986 film The Terrorizers, a stylistically bold portrait of globalization and alienation in contemporary Taipei that won the Silver Leopard at the Locarno Film Festival. Last month, Hung spoke with me via Skype about his working relationship with Yang, as well as A Brighter Summer Day’s truncated distribution and slow path to critical acclaim, and the real-life roots of its intricate narrative. (I translated Hung’s remarks into English; our original conversation was conducted in Mandarin.)

How did you first meet Edward Yang, and how did you come to start working with him?

I was studying theater at university, and my professor, Lai Sheng-chuan [Stan Lai], was a friend of Hou Hsiao-hsien, Edward Yang, and other figures in the New Taiwan Cinema. When I became interested in working in movies, Professor Lai introduced me to Edward. During my summer vacation in 1986, I went to work on his film The Terrorizers as an assistant director.

You’re one of four screenwriters credited on A Brighter Summer Day. Could you describe your collaboration, and who was responsible for which parts of the writing process?

The other screenwriters on A Brighter Summer Day were Lai Ming-tang and Yang Shunqing [credited as Alex Yang]. Lai Ming-tang was one of Yang’s assistant directors, and though he had never been credited as a screenwriter before, he was always an integral part of Yang’s filmmaking process. He helped with location scouting, art direction, and other areas, so he was someone with a unique understanding of what Edward was after. Yang Shunqing and I were brought onto the team later. Edward wanted to collaborate with younger screenwriters, and I had just finished my mandatory military service and had been working for about a year.

How much of the screenplay was based on Yang’s personal experiences?

A lot of it came not just from Edward’s experience but from what he had observed in the lives of his family and friends. Although the film was based on an actual youth murder that took place in Taipei, that incident served merely as the shell of the story, a container for Edward’s own reminiscences.

Having been born almost two decades after Yang, did you find any of the period details in the film difficult to grasp?

Not really, because I also grew up waisheng ren [a descendant of ethnic Chinese who arrived in Taiwan after the Chinese Communist Revolution began in 1949]. Though I was born in 1964, a lot of what Edward was capturing in the film were things that I had also experienced. During the screenwriting process, I was responsible for collecting archival materials from that era. Edward would have me gather old newspapers, and this made it easier to understand what was going on in that period. One of the harder things to grasp was the world of youth gangs. Neither Edward nor I had been in one, but we had observed others who had. A lot of what you see in the film with regards to gang activity is the product of inference and speculation, not actual fact.

What made Yang interested in adapting a news story?

Even before The Terrorizers, Edward was already interested in making A Brighter Summer Day, and in many ways the two films have important thematic parallels—particularly this idea of a society killing its own people. The Terrorizers was about a contemporary moment in the 1980s, and you could say A Brighter Summer Day goes back and imagines how these “terrorizers” grew up. Edward wanted to understand how this social instability and fear took hold, and how these people came to be who they were.

In the 1980s, there was an infamous case involving an aboriginal Taiwanese youth named Tang Yingshen, who had come to the city to work, was abused and exploited, and ended up killing his boss and his boss’s family. At the time, a lot of people came out in support of him, but ultimately he was sentenced to death. Edward followed the case closely, and although he never said so explicitly, I think the memories it stirred up for him served as an entry point into the film.

How was the film seen and distributed in Taiwan and abroad?

The international distribution was disappointing for Edward. His initial hope was that the film would play at Cannes, but it wasn’t accepted—he was told it was because there were too many long films that year. It did make it into a few international festivals, but it didn’t enjoy a great reception. It wasn’t until the film screened in France and later in Japan that it began getting some acclaim.

At the time, the local distributors wouldn’t release a film that was four hours long, so he edited together a three-hour version, which he was never satisfied with. It was this shorter version that Taiwanese audiences were first exposed to. I remember that friends of mine didn’t think much of the film, saying there were some problems with the performances and the plot structure. But they completely changed their minds when they saw the full version. After the film won some international acclaim, it came back to Taiwan in an extremely limited release, and people much preferred the four-hour cut.

Do you remember which parts were removed for the three-hour version?

The biggest omissions were the scenes involving Xiao Si’r’s father and the White Terror [a period of martial law between 1949 and 1987, during which Taiwan’s Kuomintang government suppressed political dissidents]. The shorter version took the focus off of the political content and placed it more heavily on the stories of the children.

There actually weren’t any limitations. The controversy surrounding A City of Sadness had more to do with the fact that it depicted the 228 Incident [an infamous massacre that took place on February 28, 1947, in which tens of thousands of Taiwanese protesters were killed by the Kuomintang government]. Although martial law had ended, there was still very little public discussion of 228, so the film did cause a stir—though ultimately it was never censored. A City of Sadness reflected the experience of bensheng ren [the ethnic Chinese who established roots in Taiwan before the beginning of the Chinese Communist Revolution in 1949].

The White Terror, which is depicted in A Brighter Summer Day, was an experience shared by everyone, both bensheng ren and waisheng ren. And A Brighter Summer Day wasn’t the only film to discuss it; there was also Wan Jen’s Super Citizen Ko (1995). So that part of the film wasn’t particularly controversial, and Edward wasn’t interested in provoking anyone with that subject matter.

_medium.jpg)

We never really discussed this during the screenwriting process, but I don’t think Edward really cared about that—otherwise he wouldn’t have made the plot so complicated. It’s not that Edward was ignoring foreign audiences in particular; it’s just that he wasn’t really concerned with any viewer other than himself. If you think of his film A Confucian Confusion, it’s so packed with dialogue, a foreign viewer would barely be able to keep up with the subtitles.

In A Brighter Summer Day, he doesn’t bother to explain the different gangs and their backgrounds; he simply uses the expressions of the actors to hint that some are the children of military families and some are the children of civil servants. This is a distinction that foreign audiences and even Taiwanese viewers who did not live through that era would have a tough time ascertaining. But it wasn’t our goal to give the viewer a thorough explanation of each and every character; as long as they were compelling, that was enough for us.

Edward studied and worked in the U.S. in the 1970s, so I imagine he was somewhat removed from the politics of Taiwan in that period. How do you think this influenced the views of Taiwan that are reflected in his films?

Professor Lai and Edward used to play basketball and speak English together, and we’d joke about them being “Americans.” I think being able to stand on the sidelines as an observer, an outsider, gave Edward the courage to raise certain questions in the film. He had actually experienced or observed the world he was depicting in A Brighter Summer Day, but after living abroad, he had a stronger sense of the contrast between the social freedoms in the U.S. and the repression in Taiwan. This gave him a unique ability to perceive and grapple with the social problems back home.

Were there any films that he or you drew inspiration from while making A Brighter Summer Day?

I’m sure there were, but we didn’t discuss this. The one exception was Scorsese, particularly Goodfellas, which Edward used as the model of a gangster movie. But Edward’s style was completely different from Scorsese’s. People often refer to Edward as someone influenced by European filmmakers, comparing him to Antonioni, but he wasn’t intentionally imitating anyone. What I think did have a huge influence on him was the auteurist spirit you find in European cinema. He knew the importance of expressing oneself and having a style of one’s own. It was under this influence that he learned not to fear making films that were too difficult, and not to fear the audience’s incomprehension. But I think this influence was primarily one of attitude, not of aesthetics.