Haskell Wexler: An Insider Outlier

When the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences created a second cinematography Oscar for color films in 1939, it was simply acknowledging the growing audience appeal of the still new three-strip Technicolor format. Ernest Haller and Ray Rennahan shared that first Oscar for color for their work on Gone With the Wind, while Gregg Toland won for his black-and-white cinematography of Wuthering Heights.

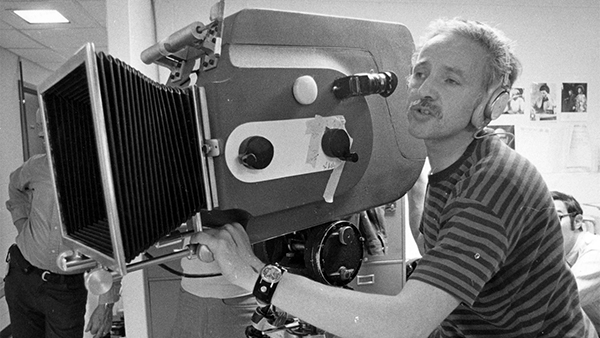

By the mid-1960s films photographed in black and white were so few that 1966 was the last year the Academy awarded a separate Oscar in that category. That award went not to veteran James Wong Howe for his bold lensing of the John Frankenheimer film Seconds, but to a brash industry outsider for his controversial cinematography of Mike Nichols’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? The cinematographer was a passionate documentarian from Chicago named Haskell Wexler; his friend Conrad Hall had been nominated the year before for his black-and-white work on Bernhard Wicki’s Morituri. During the next several decades these two men redefined American cinematography, ultimately garnering fifteen nominations between them, five of which resulted in Oscar wins.

Connie died in 2003 at age seventy-six. Haskell forged on, seemingly impervious to time, active in the industry, in the International Cinematographers Guild, and in the American Society of Cinematographers, still making edgy documentaries with his “prosumer” video cameras right up to his sudden death at age ninety-three, on December 27 of last year.

While much of Haskell’s Hollywood work is a veritable roll call of the most memorable dramas of the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s—In the Heat of the Night, The Conversation, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Bound for Glory (for which he won his second Oscar), and Matewan, to name a few—his career-long stream of nonfiction films was nearly equally impressive, embodying a deeply activist social and political commitment, his sense of justice seeming to continually stoke not just his camera but the depths of his very soul.

One of his later documentaries, Who Needs Sleep?, is a call to action to the film industry itself against unreasonable working hours for crew members. The film was prompted by the death of camera assistant Brent Hershman, who fell asleep while driving home after a nineteen-hour shooting day during the production of 1998’s Pleasantville. For years after Hershman’s death, Haskell continued to argue for the adoption of a mandatory twelve-hour workday limit, sparking controversy, even among the ranks of fellow crew members, many of whom could see limited work hours not as a humane imperative but only as a pay cut. It is a testament to Haskell’s courage and focus that after decades of involvement with topics of broad national and international interest, he boldly pointed his lens into his own backyard, unafraid to speak out to an industry rife with fears of personal career implosion.

Haskell may have had the wealthy man’s luxury of being able to speak and act publicly and loudly with impunity, but his fiscal independence was not what drove him. One look at his roster of documentaries (from The Living City in 1953 and The Bus in 1965 to Four Days in Chicago in 2013) is all the evidence one needs to know that Haskell Wexler always put his camera where many others only put their mouths—or their wallets. His nonfans, of which there were many inside and outside of Hollywood—Haskell never shied away from controversy—were always outflanked by his singular passion for whatever cause he took on. According to an in-depth tribute piece in The Guardian in December, Haskell even achieved the prime status of being put on J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI surveillance rolls, probably as a result of his feature directorial debut, Medium Cool, which was set against the demonstrations of the 1968 Democratic National Convention, in Chicago, and his photography of Underground, a polarizing 1976 documentary on the militant activist group the Weather Underground. The FBI said that Wexler was “potentially dangerous because of background, emotional instability, or activity in groups engaged in activities inimical to the United States”—Haskell’s camera lens as metaphor for a gun or bomb.

My own relationship with Haskell most recently had been as a fellow member of the ASC’s Board of Governors. But way before that, it was as one of eight partners who acquired a parcel of remote land near Isabella Lake, in California, just outside the Sequoia National Forest and intersected by the Pacific Crest Trail. In 1981, a group of us erstwhile 1960s dissidents, including the editor of Medium Cool, Paul Golding, and the writing/acting/directing spouses Patricia Knop and Zalman King, purchased 640 acres of high-desert land, miles off the power grid. We designated it a nature reserve, “Piute Partnership,” meant for our and our heirs’ low-impact use and future preservation. We built a partners’ cabin and though Haskell seldom made the demanding drive to the spot (the last twenty-five miles being over a dirt road, culminating in a barely maintained fire road, graded only once a year, if at all), he was an active voice at our group meetings, always arguing for the ideal of maintaining the land against any encroaching development, even as rows of wind turbines were erected along the crest of Jawbone Canyon Road. I think it was the idea of this protected land that appealed to Haskell, a kind of poke in the eye to potential exploitation and development of the fragile land.

Haskell Wexler wore many hats—he was an independent, impassioned documentarian; a commercial Hollywood cinematographer; a political and social activist; an institutional (even union) contrarian—but he was for me (who came out of film school as a wannabe cinematographer) an exemplar of how to live, where your day work, your social and moral values, and your sense of a meaningful artistic life need not be separate parts of your being but could flow into and through each other in a rich mix, to make the whole of your life a heady brew that—like the title of Haskell’s son Mark’s 2004 documentary on him—proclaims, Tell Them Who You Are.

A longer version of this post can be found on John Bailey’s blog, John's Bailiwick, which is published on the website of the American Society of Cinematographers.