Michael Atkinson’s Top10

Michael Atkinson writes film criticism for IFC.com, Sight & Sound, and Moving Image Source. His books include Exile Cinema: Filmmakers at Work Beyond Hollywood and the novel Hemingway Deadlights. His writing for Criterion includes essays for Wings of Desire and Vivre sa vie. For this top ten, Atkinson writes, “my criteria, so to speak, are thus: these ten, plopped down in no meaningful order, may not be the films I absolutely think are the absolute best in the catalogue, but they are very, very close; more specifically, they are the repeatables, the never-get-olds, the chest-clutching nonpareils.”

-

1

Carl Th. Dreyer

The Passion of Joan of Arc

Not actually a “spiritual” work at all (if only someone could define terms like that for me), this is the first truly great film about institutional oppression (forget the Soviets’ chockablock puppeteering and jigsaw manipulations), a subject that always manages to give a film with this much passionate force pertinence in virtually any age and political climate. It took me years to realize—and this is all the props George Lucas will get from me at this late date—that Dreyer’s film is in fact an abstracted dystopian horror film, a point Lucas made by remaking it as THX 1138, right down to the shaved skulls, white-on-white compositions, inarticulate victim protagonist, looming totalitarian machinations, and semihopeless action finale.

-

2

Monte Hellman

Two-Lane Blacktop

Ah, the days when Hollywood harbored existentialistic realists, and the entirety of America—from its back roads and highway saloons to its hinterland betting subcultures, working-class desolation, gone-wild farm fields, and small-town cafeterias—was a metaphor for itself, and for all of our postwar lostness. Monte Hellman’s career peak is easily the greatest film I never even heard of as a film-hungry 1970s kid, vanished and hardly ever TV-broadcast, even as I thought the sobering, grown-up likes of Deliverance and Chinatown and Scarecrow were emblematic of an American cinema that had finally reached adulthood. Then came Star Wars.

-

3

Jean-Luc Godard

Pierrot le fou

If you’re forced to pick a sixties Godard, you do it without worry and with as much Godardian esprit, whimsy, impulse, and movie love as you can, and no one’s choice can be better or worse than anyone else’s. I can’t say exactly why this one is my favorite—it’s a vacation travelogue amid genial diatribes and ironic pastiches, four-dimensional masterpieces all—but I can say that when I interviewed Anna Karina (who is very tall, by the way), she guessed that it was, and she also kissed me.

-

4

Yasujiro Ozu

Late Spring

Gotta have Ozu, and this one seems to me to be the gentlest. Any would do, of course.

-

5 (tie)

Luis Buñuel

The Exterminating Angel

-

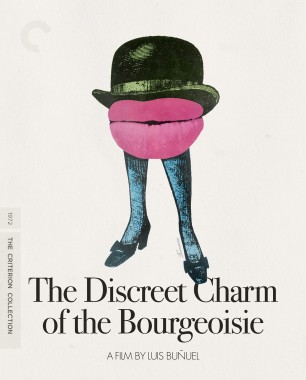

Luis Buñuel

The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie

The great Buñuelian diptych on the oddity of the Western social meal ritual, which of course is merely a filter with a distinct mesh dense enough to catch human absurdities big and small, perverse and banal, greedy and self-delusional. Surrealist is such a silly, debased, and inadequate term for full-flower Buñuel; in fact, the best Mexican and French films are birds of paradise belonging to their own exclusive breed. You can put them only in cages with Buñuel’s name on them.

-

6

David Cronenberg

Dead Ringers

The moment Cronenberg’s adorable but pulpy ideas became art, and it remains a flash-flood experience in brotherly anxiety and the unknowability of flesh.

-

7

Gus Van Sant

My Own Private Idaho

Living proof that masterpieces can be virtually defined by their imperfections, their rangy, headlong energy, their unwillingness to be defined by preexisting codes and preexisting experiences. Gus Van Sant isn’t likely to bump his head on the ceiling of this delirious odyssey anytime soon, and no other American indie-maker will either, even with its Shakespearean absurdities, quasi-doc ramblings, and dreamish non sequiturs. It’s a film that should’ve defined a generation, but strangely it seems to have been semiforgotten in the years since it came out.

-

8

Abbas Kiarostami

Taste of Cherry

Kiarostami’s world-beating mystery is less about method and meta than the filmmaker usually prefers, but the immediacy of its peril and intimacy of its reality are pure soul glue. Such is the film’s veracity that I didn’t see the three-part schematic construction of it until I’d seen it four times, by which point it ceased to make a difference. The ending, for simply being itself without apologies, is peerless.

-

9

Jean Renoir

The Rules of the Game

Nothing much new could be said here, except that you leave it out of any best-of accounting at your peril.

-

10

René Clair

À nous la liberté

I wrote the notes to this one, so suffice it right now that this fairy dystopia comes close to being an idealization of what I love about movies—it’s the paradigmatic spring-afternoon-as-film, the living idea that speaks most clearly to the boy I once was and in some ways wish I was still. I miss that kid.