Books: Godard, Kael, and More

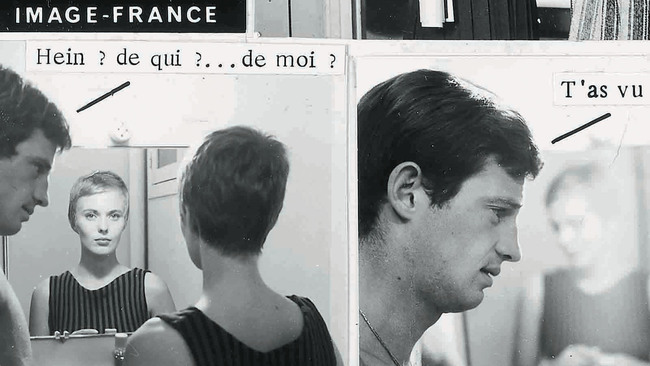

From Éditions Matière comes Contrebandes Godard 1960-1968, a collection of promotional materials inspired by comics and the Situationists for the films Godard made during those years, unpublished since but now gathered and commented on by Pierre Pinchon, who teaches at Aix-Marseilles University. Even those who, like me, don’t read French will want to see the page for the book, as well as the examples Pinchon writes about for Trois Couleurs.

In the run-up to the opening of Chris Marker: Les 7 vies d’un cinéaste, an exhibition opening at the Cinémathèque française on May 3 and moving on to BOZAR in Brussels in September, Sabzian has gathered news of several relevant volumes already out now or on their way.

“The Hollywood blacklist is one of the most written about eras of film history but also one of the least understood,” writes Christopher Yogerst for the Washington Post. Thomas Doherty’s Show Trial: Hollywood, HUAC, and the Birth of the Blacklist “presents readers with the tumultuous state of labor relations in the American film industry that led to several investigations into Hollywood, culminating in 1947.” And it’s “likely to become the standard authority on the genesis of the Hollywood blacklist.”

Tom Shone reviews Noah Isenberg’s We'll Always Have Casablanca: The Life, Legend and Afterlife of Hollywood’s Most Beloved Movie and Alan K. Rode’s Michael Curtiz: A Life in Film for the New Statesman:

Bogart was the lone American; you also had Bergman (Sweden), Claude Rains and Sydney Greenstreet (England), Paul Henreid (Austria), Conrad Veidt (Germany) and Peter Lorre, originally from Slovakia by way of London, who said that, like Brecht, he had changed countries “oftener than our shoes.” Hungarian S. Z. Sakall, who played the head waiter, lost three sisters to the concentration camps.

The director Michael Curtiz, himself a Hungarian Jew, cast them all personally, incorporating some of their stories into the movie: the trading of jewelery for exit visas, the presence of pickpockets. There were so many German Jews playing the very Nazis they had fled that German was frequently spoken on set, which was known as the International House. When the time came for the scene in which Victor Laszlo defiantly sings “La Marseillaise,” one character actor noticed everyone was crying: “I suddenly realized they were all real refugees.”

“In Sharp: The Women Who Made an Art of Having an Opinion, Michelle Dean unearths archival material that connects the lives of ten female critics who shaped the literary landscape in the twentieth century,” writes Anna Furman at the top of her interview with the author for Hazlitt. “From Dorothy Parker and Rebecca West to Nora Ephron and Renata Adler, this historical account of their work is anchored to what Dean calls ‘sharpness’—a quality that short-sided, misogynistic critics often characterize in patronizing terms.”

“At nearly every other turn, these women—few of whom explicitly identified as feminist, and some of whom were vocally critical of the women’s movement—sparred with the people around them, and not infrequently with one another,” writes Lindsay Zoladz, reviewing Sharp for the Ringer. Pauline Kael, for example, said of Play It As It Lays (1970), “‘I found the Joan Didion novel to be ridiculously swank, and I read it between bouts of disbelieving giggles.’ Didion, for her part, later documented her take on Kael’s criticism in the NYRB (‘I used to wonder how Pauline Kael, say, could slip in and out of such airy subordinate clauses as “now that the studios are collapsing,” or how she could so misread the labyrinthine propriety of Industry evenings as to characterize “Hollywood wives” as women “whose jaws get a hard set from the nights when they sit soberly at parties waiting for their sloshed geniuses to take them home”’).”

And the New Republic has posted an excerpt from from the chapter on Kael in Sharp:

Despite becoming known later in her life as a defender of popular taste in movies, a defender of visceral reactions, she had larger questions about them: about the quality of the ideas they represented, about the way they fitted into the larger puzzle of both cultural and intellectual life in America. Another was the exuberant energy that would eventually become the Kael trademark. Her personality emerges mostly in the vigor with which she analyzes something, turning it over, looking for clues. Another was that, interested in the mass audience as she was, she would never be afraid of kicking a popular phenomenon in the teeth. Kael’s role as a critic, she believed, was to run roughshod over the politics of reputation. This did not make her popular.

Last summer, about a week after the death of Sam Shepard,Madelaine Lucas stopped by the Harry Ransom Center in Austin to have a look—a close look—at the playwright’s notebooks. She and her new husband were on a cross-country road trip “largely inspired by Shepard’s collaboration with German filmmaker Wim Wenders, Paris, Texas,” she writes at the Literary Hub. “Viewing these papers at the Harry Ransom Center in close proximity to his death gave certain fragments a heightened power. One in particular jumped out at me, sent a shiver down my spine in the climate-controlled library. It was undated, scrawled horizontally across the page: I know that I am dead but I have not given up on the possibility of living. How else can I explain the uncanny feeling of turning these pages except to say that it felt like brushing hands with a ghost?”

“In Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke, and the Making of a Masterpiece, the writer and filmmaker Michael Benson takes us on a different kind of trip: the long journey from the film’s conception to its opening and beyond.” Dan Chiasson for the New Yorker: “The power of the movie has always been unusually bound up with the story of how it was made. In 1966, Jeremy Bernstein profiled Kubrick on the 2001 set for the New Yorker, and behind-the-scenes accounts with titles like ‘The Making of Kubrick’s 2001’ began appearing soon after the movie’s release. The grandeur of 2001—the product of two men, Clarke and Kubrick, who were sweetly awestruck by the thought of infinite space—required, in its execution, micromanagement of a previously unimaginable degree.”

Marlene Dietrich was “known for her professional relationships with photographers—from Cecil Beaton to Irving Penn—each of whom captured her own unique aesthetic,” writes Hannah Tindle. “A newly published book titled Obsession: Marlene Dietrich chronicles such portraits, taken from the personal collection of Pierre Passebon—an aficionado of the butchcamp femme fatale.” AnOther presents a selection of images and “ten little-known facts about her life.”

“It’s a miracle that Edna Ferber’s novel Giant ever made it to the big screen, according to Don Graham,” writes Joe O’Connell in the Austin Chronicle. “Texans overwhelmingly despised the Texas epic novel penned by an outsider who played to all of the stereotypes of their land and people. Even more miraculous was when film production came to Marfa, Texas. ‘I was surprised by the absolute magnitude of the undertaking. Even shooting in Texas was a major decision then,’ said Graham, the longtime University of Texas J. Frank Dobie Regents Professor in American and English Literature, who recounts the story of the production in his new book Giant: Elizabeth Taylor, Rock Hudson, James Dean, Edna Ferber, and the Making of a Legendary American Film.”

James Layton and David Pierce, authors of King of Jazz: Paul Whiteman's Technicolor Revue, are Michael Gebert’s guests on NitrateVille (57’53”).

From Steidl Books: “After The Americans,The Lines of My Hand is arguably Robert Frank’s most important book and without doubt the publication that established his autobiographical, sometimes confessional, approach to bookmaking. The book was originally published by Yugensha in Tokyo in 1972, and this new Steidl edition, made in close collaboration with Robert Frank, follows and updates the first US edition by Lustrum Press of 1972.”

At Fonts in Use, Quentin Schmerber presents a typographical history of Katsuhiro Otomo’s landmark manga series, Akira.

For One Grand Books, Rose McGowan has written up a list of her ten favorite books.

For news and items of interest throughout the day, every day, follow @CriterionDaily.