60s Verité

“Tapping into the cultural, social and political anxieties that are tipping our country toward another revolution, Carnegie Hall has rallied some of the biggest institutions in the city for The ‘60s: The Years That Changed America,” writes Eva Kis for Metro—and the city is, of course, New York. “Officially going on now through March 24 (though some exhibits have already started and others will continue past that date), The ‘60s brings together over thirty-five organizations from the Museum of Modern Art to Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater staging more than fifty exhibitions, concerts, talks and more about the decade that reshaped American culture.”

And then there’s the nineteen-day, sixty-four-film series curated by Elspeth Carroll, 60s Verité, opening today at Film Forum and running through February 6. “Taken together,” writes Flavorwire’s Jason Bailey, these films “shed some much-needed light on the often understated influence of this non-fiction style on the fiction films that followed them. The series includes a handful of narrative efforts that clearly convey that influence (like [John Cassavetes’s] Faces [1968] and [Agnès Varda’s] Cléo from 5 to 7 [1962]), but said influence goes beyond copping the handheld, run-and-gun aesthetic. These films explored a naturalism in staging (and often even with traditional editing) that would, at long last, match the naturalism in acting that was practiced by Marlon Brando, Paul Newman, Warren Beatty, and other students of Method acting, yet was often stifled by the stiffness of the studio style.”

Before we go any further, Chadwick Jenkins, arguing at PopMatters that “the charismatic presences that inform the festival as a whole are Jean Rouch, one of the progenitors of cinéma verité, and Robert Drew, the driving force behind direct cinema,” wants to be sure we understand that these are two distinct terms. “These approaches had much in common and yet differed in significant ways that can all-too-easily be overlooked. Understanding these differences is essential when coming to grips with the ethical character that resides at the heart of these filmic projects. . . . Drew's ‘direct cinema’ is far less reflexive (especially in the first decade of his output) than Rouch's cinéma verité. Drew's films make a concerted effort to efface, insofar as possible, the presence of the filmmaker. . . . Whereas Rouch acknowledges that ‘theater’ happens whenever anyone is actively looking (such as a camera), Drew seems to understand life itself as an endless theater (a theatrum mundi) that is best understood by not intervening.”

“Primary (1960), the landmark work of the Drew canon, provided viewers with unprecedentedly candid access to John F. Kennedy and Hubert Humphrey as they vied for the Democratic nomination for president that year,” writes Melissa Anderson at 4Columns. “The film is the inaugural of four Drew and company would make about Kennedy, the first direct cinema ‘star.’” Anderson also writes about Jane (1962), “which Drew directed with Hope Ryden and D.A. Pennebaker, centers on the weeks leading up to the Broadway opening of a comedy starring Jane Fonda, then twenty-four and only two years into her vocation”; A Visit with Truman Capote (1966), directed by Albert and David Maysles and Charlotte Zwerin, “all of whom were once affiliated with Drew Associates”; and Shirley Clarke’s Portrait of Jason (1967), “a densely layered examination of a loquacious black gay hustler,” which “underscores the fallacy of the documentarian’s claim to neutrality.”

The French Embassy naturally wants you to catch the nine films in the series by Rouch, “an inspiration for the French New Wave, and a revolutionary force in ethnography and the study of Africa. Astonishing on their own terms, and now restored in high-definition, [these] classic films and restorations [are] essential for anyone interested in better understanding the development of ethnography and the cross-currents of colonialism and post-colonial social change in Africa, as well as documentary film practice, film history, and world cinema as a whole.”

For Eric Monder at Film Journal International, what’s “extra-special” about “this particular series are the collection of long and short documentaries by little-known filmmakers that have not been seen in years—if ever at all. Look out for: Dick Fontaine’s Will the Real Norman Mailer Please Stand Up? (1968), with theperipatetic novelist making movies, giving interviews and demonstrating against the Vietnam War; Frank Simon’s The Queen (1968), a pre-Paris Is Burning drag queen contest; Peter Lennon’s Rocky Road to Dublin (1968), about the ordeal of the Troubles (with a cameo by John Huston!); Allan King’s A Married Couple (1969), a Bergmanesque ‘actuality drama’ starring a free-spirited Canadian couple; Thomas Reichman’s Mingus (1968), a searing look at jazz artist Charles Mingus—in the midst of being evicted from his home; and most surreal of all, two late career (1965) last hurrahs for Buster Keaton, Gerald Potterton’s The Railrodder and John Spotton’s Buster Keaton Rides Again.”

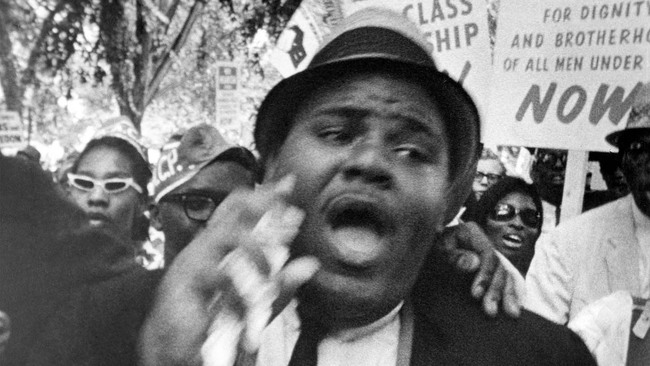

Image at the top: Haskell Wexler’s The Bus (1964), screening Tuesday.

Update: For the Notebook, Adrian Curry has put together a gallery of movie posters that “convey the urgency of the movement as well as its seat-of-the-pants guerrilla style of film marketing as much as film making.”

Update, 1/22:Chloe Lizotte for Screen Slate on Allan King’s A Married Couple, screening Thursday: “For ten weeks, King sent a two-person crew (cinematographer Richard Leiterman and sound technician Chris Wrangler) to film his friends Billy and Antoinette Edwards, who (mostly) ditched the bohemian ’60s for the allure of upper-middle-class married life in Toronto, from morning until night,” and “it’s still shocking how nakedly the Edwardses interact with one another throughout the film, not just in explosive arguments, but also in more gestural moments of domestic awkwardness. . . . Time’s reviewer (whose name may, unfortunately and fittingly, be lost to time) declared that A Married Couple ‘makes Cassavetes’s Faces look like early Doris Day’ . . . so keep in mind, Faces plays afterwards at 8:30.”

Update, 2/1: Jim McBride’s David Holzman’s Diary (1967) starring L. M. Kit Carson “is evergreen,” writes Jon Dieringer at Screen Slate, “a movie that must be referenced in terms of its engagement with slippery notions of truth; its probing of the relationship of the individual to the world and the self as increasingly mediated in an audiovisual space; and its cunning and trailblazing use of the faux-documentary format as a vehicle for satire and narrative sleight-of-hand. It is also a portrait of a completely insufferable cinephile.”

For news and items of interest throughout the day, every day, follow @CriterionDaily.