Carlo Di Palma, “from Rome to New York”

Shot by Carlo Di Palma, from Rome to New York is the title of the Film Society of Lincoln Center series celebrating the work of the cinematographer who worked with some of Italy’s greatest directors before moving to the States in 1983 to shoot, most famously, twelve films for Woody Allen. He passed away in 2004, and last year, his widow, Adriana Chiesa Di Palma, oversaw a documentary, Water and Sugar: Carlo Di Palma, The Colours of Life, directed by Fariboz Kamkari. Like the series, it sees a week-long run at the FSLC starting Friday.

“Di Palma emerges as a master of light and color, someone who started out in the Italian neorealist cinema after the war, brilliant at working with whatever light was available on location,” writes the Guardian’s Peter Bradshaw, one of the film’s few admirers, actually. He spotlights the way that “this documentary argues that it was Di Palma who brought a cosmopolitan, Europeanized look to Allen’s New York—it demonstrates the micro-energies of a traveling shot he devised for the restaurant quarrel scene in Hannah and Her Sisters [1986].”

Writing for the Observer,Wendy Ide grants that Water and Sugar is “well intentioned and reverential but it feels like a tombstone for the oeuvre of a man whose photography was vividly, mercurially alive.” In the Village Voice,Danny King agrees that the “life and accomplishments are touted here with all the excitement of an afternoon nap.”

When it screened in Toronto last fall, Robert Koehler, writing for Cinema Scope, suggested that “the best part of this misbegotten project is documenting how Di Palma learned as a young man under the neorealist masters; he was fifteen when he got a job on the crew for Visconti’s Ossessione (1943), essentially neorealism’s point of origin. His training ground included titles such as Visconti’s La terra trema (1948), De Sica’s Shoeshine (1946) and Bicycle Thieves (1948) and Antonioni’s Story of a Love Affair (1950) and Il grido (1957), where he worked under Gianni Di Venanzo, the greatest of pre-1960s Italian cameramen. Many of the clip selections are intelligent: a scene from Ossessione, on which Di Palma worked as focus puller, displays a fine example of shifting focus inside a moving shot with great depth of field. But the key bits on his revolutionary work with Antonioni, particularly on Red Desert [1964] and Blow-Up [1966]—a better back-to-back set of home runs doesn’t exist in the annals of color cinematography—fall short of the mark.”

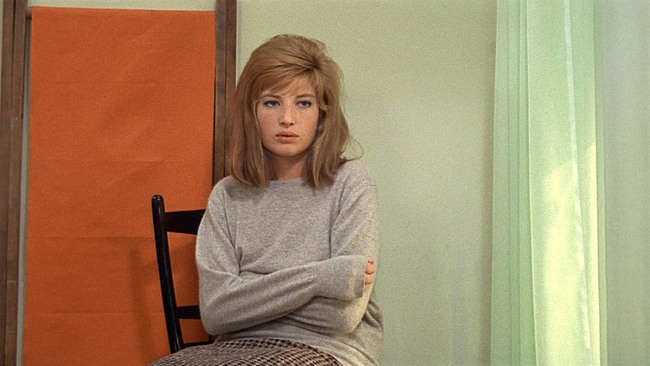

For more on Red Desert (image above), see the entry at Critics Round Up.Blow-Up, in the meantime, also opens on Friday for a week-long, but at Film Forum. “Antonioni, it has been said, was less interested in people than in the space between them—whether that space was architectural, natural, or just plain blank,” writes Bilge Ebiri in the Village Voice. “That’s often the case in Blow-Up as well—as captured by Carlo Di Palma’s camera (and gorgeously rendered in this restoration), the world Thomas walks through is beautiful and alien, somehow both lived-in and curiously empty.”

And from Chuck Bowen at Slant: “Antonioni purges filmmaking of much of its theatricality, emphasizing strands of cinematic DNA that have their roots in dance, painting, architecture, and photography, celebrating the power of negative space as a revealer of emotional texture.”

Bilge Ebiri has another recommendation, Bernardo Bertolucci’s Tragedy of a Ridiculous Man (1981), screening Tuesday as part of the FSLC series. “Di Palma’s autumnal, lived-in images . . . turn out to be ideal for a tale so perplexing, tragicomic, and human.”

Updates, 7/28: “The only thing more consistent than the quality of Carlo Di Palma’s cinematography is the routine variance of his work,” writes Jeremy Carr in the Notebook. “His decades-spanning career produced a gallery of fluctuating colors, lighting techniques, temperatures, movements, and tones. And more often than not, what he refined in this richly varying field proved to be a directly corresponding realization of profound psychological consequence.” Carr then focuses on Red Desert and Husbands and Wives.

More on those two, too, from Tanner Tafelski at Kinoscope, noting that Red Desert “is known for its color, but that’s because Di Palma eliminates many colors, thereby accentuating those that are still in the shots. . . . In Hannah and Her Sisters, his first collaboration with Allen, Di Palma creates a dampened color palette. It’s muted and flat, yet not uninviting or dreary, but rather organic.”

For the New York Times,Teo Bugbee reviews Water and Sugar, “an official history, focused more on work than pleasure or even personality.”

Update, 7/29:Adrian Curry’s put together a gallery of posters for Blow-Up at the Notebook.

Update, 8/1:September (1986) is “prime Woody Allen,” writes Patrick Dahl at Screen Slate, “something like the visual and dramatic median of his output. It’s full of self-regarding, wealthy New Yorkers bathed in gorgeous light, mulling existence and their relationships with equal concern. The light comes courtesy of a cinematographer seemingly working apart from Allen’s clever script, and the performances rank among each actor’s finest work. There’s also languid jazz on the soundtrack. The only thing missing is Allen himself on-screen.”

For news and items of interest throughout the day, every day, follow @CriterionDaily.